I reckon I am not the only amateur who loves M31,

“Andromeda,” as me and my buddies in the legendary Backyard Astronomy Society

called it when we were kids. And I am probably not the only amateur who’s had a

decades long love-hate relationship with the big galaxy. For Unk it was most

assuredly more hate than love in the beginning.

What was it that li’l Unk longed to see more than anything

else in the months between his first look through a telescope that seemed

attainable, Stephanie’s Telescope, and receiving

his 3-inch Tasco reflector? Which pictures did he spend hours mooning over in Stars

and in Universe (from the old Science Service), his only two astronomy

books? Why galaxies, of course.

Gorgeous spirals like M101 and amazing edge-ons like M104.

When Daddy came into li’l Unk’s bedroom early one spring

morning in 1965 bearing that Tasco in his arms, I felt like the whole Universe was about to

open before me. I was realistic, however. I’d learned enough from the only advanced astronomy book Mama had on her shelves at Kate Shepard Elementary, Patrick

Moore and Percy Wilkins’ How to Make and

Use a Telescope, that 3-inches might be a little small for looking at most galaxies.

That was OK. I’d also learned M31, The Andromeda Nebula (as it was still often called

in them days), was close, big, and bright and would be coming round with the

autumn stars in just a few months.

Not that I didn’t hunt a few of the spring galaxies before

then. To no avail. I didn’t know what a galaxy should look like in my

telescope, and especially not how dim even the ones the books called “bright”

would be—I thought M51, for example, should look about as bright in my eyepiece

as it did in the pictures, just smaller.

It also didn’t help that my scope didn’t

have a finder—it had a pair of peep-sights instead—and that I had no idea how

to star hop. Even if I'd had an inkling of how to locate objects I couldn't see

with my naked eye, I didn't have star charts good enough to help me do so.

I had plenty of fun with the few deep sky objects I could find, mostly bright open clusters.

The Tasco’s optics were on the putrid side,

and stars and star clusters looked considerably better in her than the Moon and

planets. Still, that was just a prelude. As soon as September, I knew, knew,

I’d be glorying in the sight of the huge spiral M31.

When school let back in and Andromeda and Pegasus began

lifting over the horizon, you can bet I was out there with my telescope. On the

weekends, at least. Much as I wanted to get out every clear night, Mama would not

hear of it on school nights, even if I’d already done my homework, and it looked like that was the way it would stay at least through junior high! Observing was

not allowed till Friday evening. Not until months and months after I got the scope, when I got the bright

idea of getting Daddy interested in looking through the Tasco. That was sheer

genius. All Mama would usually do was fume when Daddy announced, “The boy and I are

just going to have a quick look at the Moon.”

Anyhow, on the first clear Friday or Saturday night in late

September, I was in the front yard with the Tasco (the house

blocked objects low in the east from out back). I suppose it's amazing I managed to find M31 at all—after

about half an hour of hunting. Or maybe not so amazing. By this time, I at

least had enough sense to use my longest focal length eyepiece (about 30X) for

finding. M31 is huge enough to be hard

to miss, anyway, and I now had a subscription to Sky & Telescope and could use its monthly star chart to get me in the general vicinity of the galaxy.

I put my eye to my little .965” eyepiece expecting, as

usual, not to see nuthin’ at all, but there was indeed something there. Not much of anything, but something. What there was was a big, round fuzzy ball. I kept

staring and I eventually saw the ball was set in a streak of nebulosity that

extended well beyond the puny field of my eyepiece—likely a Huygenian with a

30-degree AFOV. At first I wasn’t convinced this was Andromeda, but a

moment’s reflection assured me it must be. All the books talked about how

bright the galaxy was, and what else even this bright would be here?

Did li’l Rod jump for joy and run into the house hollering

that the Old Man just had to come out

and look right now? Nope. I was badly disappointed and a little embarrassed for my poor little scope. The

pictures of Andromeda in my books, including the shot done by the Mount Wilson

folks, didn't make the galaxy look like M51 or M101.

M31, it was clear, didn’t have the out-flung arms of those galaxies, but

it still looked better than this mess,

this fuzzball set in a saucer of

dimmer fuzz.

But…but…everything I read insisted M31 was bright. To li’l old me, that implied my

telescope should show detail like in the pictures, just a lot smaller and maybe

a little dimmer. Well, then, could my problem be that Andromeda was still too

low in the east and in the light dome from nearby Highway 90 with its

hordes of neon-adorned motels?

So, I waited a while, till Thanksgiving Vacation—when Mama

couldn't complain about me using the telescope on a dadgum weeknight. In late November,

the sky was taking on that beautiful, dark appearance fall’s passing cold

fronts bring. Orion was peeping over the trees in the east just before Mama hollered me in each night, but the target for this evening was M31.

So, I waited a while, till Thanksgiving Vacation—when Mama

couldn't complain about me using the telescope on a dadgum weeknight. In late November,

the sky was taking on that beautiful, dark appearance fall’s passing cold

fronts bring. Orion was peeping over the trees in the east just before Mama hollered me in each night, but the target for this evening was M31.

The result was yet more disappointment. Yes, Andromeda

looked a little better. The ball looked brighter and so did the saucer it was

sitting in. But that was it. I didn’t see dark lanes or star clouds or nothing

else. The problem, I reckoned, was that my Tasco was just too puny, and, like

generations of amateur astronomers before and since, I began dreaming of MORE

APERTURE and scheming as to how to get it.

Six months later, I did have a bigger scope. It wasn’t

much bigger at 4.25-inches, and it sure

wasn’t easy to get, but I did get it. Would it help with that cursed M31? I

hoped it would, but I had my doubts. Still, I was heartened by what the book, The New Handbook of the Heavens had to say about M31:

The Great Nebula in Andromeda. This grand spiral is visible to the naked eye as a hazy star, and is the brightest spiral in the sky. A most interesting object: with low telescopic power, a large, bright elliptical mass; more detail and spiral structure are seen with larger instruments.

Most interesting,

huh? Well, that meant it had to be

more than just a fuzzball floating on a sea of thin milk, didn’t it?

Just as the Tasco had, the Palomar Junior came to me in the

spring of the year, the late spring of 1966, so I had to wait months to see

what, if anything, it would do to improve M31. At least I would be able to find

it more easily now. The combo of more aperture, a (small) finder scope, Norton's Star Atlas, and me

learning to star hop thanks to the help of my buddies in the vaunted

BAS, meant I was beginning to knock off the brighter Messiers. I was heartened

that every one of ‘em looked better than in the Tasco (those few I’d even seen in the Tasco).

“Well, hell!” Li’l Unk exclaimed at his first

sight of M31 with the 4.25-inch. It sure was a good thing Mama wasn’t in

earshot, because the words that came out of my mouth next wouldn’t just have caused her

Profanity Meter to twitch, but to redline.

The galaxy didn’t look better than it had in the Tasco; if anything, it was worse.

If the central area was brighter, it wasn’t much brighter,

and it filled more of the field, with the disk of M31 being less visible with

my new 1-inch Kellner (no silly little millimeters in them days) at 48x than it

had been with the Tasco’s lowest power, 30x. Was the Pal somehow BROKEN? Nope.

A side trip to the (bright) fuzzball of M15, which I’d conquered not long

before—with some difficulty—showed the scope seemed to be working well.

If the central area was brighter, it wasn’t much brighter,

and it filled more of the field, with the disk of M31 being less visible with

my new 1-inch Kellner (no silly little millimeters in them days) at 48x than it

had been with the Tasco’s lowest power, 30x. Was the Pal somehow BROKEN? Nope.

A side trip to the (bright) fuzzball of M15, which I’d conquered not long

before—with some difficulty—showed the scope seemed to be working well.

The obvious was finally staring me in the face. M31 was big.

Real big. What the books said regarding its size, two-and-a-half degrees, was

finally sinking in regarding just how huge this thing was in the sky. Almost

five times bigger than the field of my Kellner. While I wasn’t sure, I suspected

this large size might be the reason it didn’t look anywhere near as bright as

the magnitude I’d seen listed for it in the New Handbook, 4.3, implied it

would. That was just a suspicion, and it took a while longer for me to learn “bigger”

always equals “dimmer” when it comes to extended objects.

So, that meant a big scope wasn’t appropriate for the thing.

But who wanted to fool with small telescopes? And how did big observatories

like Mount Wilson get pictures of the whole thing? I didn’t know pea turkey

about wide-field cameras or mosaics. I just figgered they slapped a camera on the 100-inch in place of its eyepiece and snapped away, just like I did with my

Argus 75. I put it down to THE MYSTERIES OF PROFESSIONAL ASTRONOMY, and decided I

might as well just move on.

Wasn't nothing for it; I had to admit Sam Brown, in the

book that had come with the Pal,

his How to Use Your Telescope, had

nailed it. In contrast to the New Handbook’s “most interesting,” Sam opined

that all I would probably see of Messier 31 would be the round glow of the

galaxy’s center.

I suppose before we take another step, campers, I really ort-ta

stop and do the just-the-facts-ma’m thing. Messier

31, a.k.a. NGC 224, a.k.a. PGC 2557 is a type Sb spiral galaxy. It is

nearly edge-on to us, which is what prevents it from making a show with its

spiral arms, which are somewhat tightly wrapped, anyway. It is bright, as you’d

expect, since it is close, a mere 2.6-million light years away. Even in these

light polluted days, it is still visible from half-way decent suburban

locations as a fuzzy star about 4-degrees west of magnitude 3.9 Mu Andromedae,

the second star from the end of Andromeda’s western chain of suns. If you could

smoosh M31 down to a pinpoint, it would look about as bright as Mu.

|

| Down Chiefland Way... |

A small, short focal length telescope is a good telescope

for M31, but wider field eyepieces can make it better in any telescope. My

first dream scope, a Cave f/7 Newtonian I got in the 1970s, was of moderate

focal length, but my eyepieces were still of the soda straw apparent field variety.

Orthoscopics. Kellners. Even a fugitive Ramsden or two.

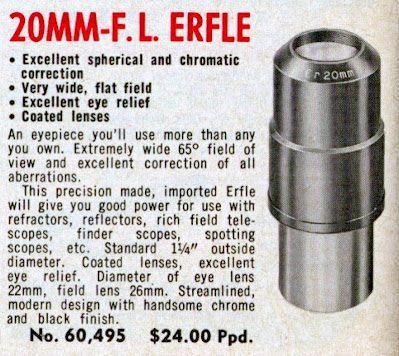

Oh, I had my eye on the More Better Gooder eyepiece-wise, a

lovely Edmund Scientific Erfle I’d wanted for a long dang time, but buying the

Cave had temporarily exhausted my treasury. Before I could get a-hold of a wider field eyepiece, I’d grown tired of hauling the long-tubed Cave into the foothills of

the Ozarks in my Dodge Dart in the dead of Arkansas winter and sold it,

replacing the Newtonian with a C8 Schmidt Cassegrain with 2000 dadgum millimeters

of focal length. Unsurprisingly, the C8 wasn’t very good for looking at M31, at

least not the galaxy as a whole, not with my eyepiece lineup.

In the years that followed, I would wander over Andromeda way

occasionally, for old time’s sake, but didn't pay serious attention to the galaxy

again for a long time. Not till the mid 1990s, when the Celestron f/6.3 reducer and

ultra-wide-field eyepieces like the Naglers made my C8 into a lean, mean Andromeda

machine.

Wider is better for

this object. Sometimes. What was brought

home to me one night at the Peach State Star Gaze, however, was not so much that, properly

equipped, the C8 could take in a lot—though hardly all—of the enormous galaxy,

but how much there was to see of Andromeda at all magnifications and field

widths.

I didn’t really set out to tour M31 at the 2001 PSSG; it

just happened. I was tired after the drive up to Jackson, Georgia and didn't

want to spend hours hunting hard stuff. M31 was bright and well-placed

for observing. Also, I’d piggybacked my new Celestron Short Tube 80 on the C8,

and I figgered that little bird ought to be a natural for the big galaxy.

I gave M31 plenty of time that night and saw one heck of a

lot, from its tiny star-like nucleus, to subtle, barely visible details near

the nucleus—hints of odd, branching dust lanes—to the immense star cloud NGC 206, to two

dark lanes in the disk. This was the

best view I’d ever had of the satellite galaxies, which were big and bold. I

didn’t stop with them, though.

I hadn’t intended to spend much, if any, time looking at M31,

but before I’d left home, I’d had the idea that if I did get around to it, I

might try for the ultimate concerning that object. I’d brought along a finder

chart that pointed the way to M31’s most prominent globular star clusters. I

spotted the brightest of them, G1, with fair ease. It didn’t look like much,

just a slightly fuzzy star, but I was gobsmacked to think my humble C8 could

show me a globular cluster of another

galaxy. The most amazing thing? When I pumped up the power, G1 actually began

to look a little like an unresolved glob. It wasn’t much different, really, from the

smudge of M15 in my 3-inch Tasco on that long ago night.

While the C8, my Ultima C8, Celeste, showed Andromeda’s

details beautifully, the Short Tube refractor delivered the big picture—in

spades. In the 80mm f/5, M31 really looked

like a galaxy for once. The little scope picked up both dark dust lanes with fair

ease, and the big disk just seemed to stretch on forever. If all I’d seen at that

star party had been that vision of the great spiral in the little ST-80, the

trip would have been worth it.

What is the best view,

overall, of the galaxy I’ve ever had? That came one special night at the 2008

Chiefland Star Party with my 12-inch Dobsonian, Old Betsy. How was it? You can

read the blog entry, “The 8mm Ethos Faces Dark Skies,” but here’s the relevant quote:

M31 was riding high, so why not?

8mm may sound like a lot of magnification to use on this elephant of a galaxy,

but it really is not, not if you want details instead of just the big picture…I

saw more of M31 than I’d seen in a long time. Heck, I don’t know I’ve ever had as good a view of this monster

with any scope.

Start with the dark lanes. Two

were starkly visible. The satellite galaxies, M32 and M110? M32 nearly ruined

my night vision. M110 was large—huge—and I seemed to see some sort of fleeting

detail near its core. Speaking of galactic nuclei, M31’s core...was not merely “star-like,” it was a tiny blazing pinpoint. I also

noticed that something I have had a lot of trouble with over the years, the

galaxy’s enormous star cloud, NGC 206, was not merely “suspected” or “visible,”

it was bright and easy.

In the years since, I’ve never quite equaled that observation,

though I came close one fairly recent night at the Deep South

Regional Star Gaze. While the galaxy was similar in majesty, NGC 206,

which I use as a yardstick to how “good” the galaxy is on any given evening,

wasn’t as prominent.

|

| DSI M31 |

How about picture taking? Curiously, I’ve never really

gotten a decent shot of Andromeda. Probably because I haven’t done much trying.

Oh, I snapped a few frames with my Yashica SLR and my Cave back in the hallowed

Day, but the question regarding my results was always, “Is that M31 or a

custard pie?” I have had several wide-field refractors in addition to the ST-80 over

the years, but only once have I slapped a camera on one and turned it to M31, and

that was kinda as an afterthought.

In January of 2009, I had a big

expedition to the Chiefland Astronomy Village planned. I was out to kill the deep sky with my NexStar 11 and

my Stellacam 2 deep sky video camera. One of Unk’s doctors put the kibosh on

that. It seemed I had developed a small and non-threatening skin cancer on my forehead that

nevertheless had to be removed, which took place the fracking day before my

trip.

Unk was not about to be robbed of his CAV fun, though Miss

Dorothy was skeptical. She was reassured when I promised I’d leave the big,

heavy 11-inch at home. I’d back off to the C8 and my CG5 German equatorial mount.

Almost as an afterthought, I threw my 66mm William Optics SD refractor and my

old Meade DSI camera into the Camry and was off.

At the site, I found the surgery had affected my stamina more

than I’d expected. It was also some of the coldest weather I have experienced down south in Florida. So, I

spent my nights at the CAV “just” looking at pretty things, both with the C8

and with the refractor, which I’d piggybacked on the SCT, and with testing new

hand control firmware.

One element of that updated firmware was Celestron’s

spanking new AllStar polar alignment procedure. How would I test its

effectiveness? Why not slap the DSI on the refractor and do some unguided

30-second shots of…well…how about M31? The resulting frames were certainly not

masterpieces, but they did show that the polar alignment system worked, and

they did allow me to claim I’d finally taken a recognizable picture of the

galaxy.

I hope to do better soon. In the past, I’ve never been much

interested in wide field photography, but that seems to be changing. As soon as

M31 is in the west and out of the Possum Swamp light dome again, I may get that old

66mm scope out of mothballs and see how she'll do on M31 with a modern DSLR.

Messier 31, the Andromeda Nebula (I guess I will never stop

calling it that), has been a challenge for your old Uncle for near 50

freaking years. I probably won't surpass that look at Andromeda down in

Chiefland in '08, but I’ve got a long way to go with it astrophotography wise. Maybe that is a

good thing, muchachos; it feels good and right that the book

isn't quite closed on Andromeda for me yet.

Next Time: Destination Moon Night 8...

Great report. Brought back many memories of using my Edmund Scientific 3" Newtonian back in the early 1960s. More recently I used my 8" LX200-ACF for some M31 DSO observing. NGC206 was easy using 83X. The open cluster C107 was more difficult but visible. The globular cluster G76 was visible at 83X using averted vision and appeared as a non-point fuzzy object at 222X. The globular cluster G1 was easy (once star-hopped to) at 83X and showed a large fuzzy disk at 222X. It was really exciting to be able to view some DSOs in our neighbor galaxy.

ReplyDeleteI know what you mean Rod. I have had friends and family who couldn't wait to see M31 with my CPC1100 with eyepiece or Mallincam. But they are never impressed. FOV is just too small and the nucleus is too bright!

ReplyDeleteI like your DSI pic of it though!

I enjoyed reading about your experiences observing M31, Rod.

ReplyDeleteOver the years, I've had some great views of the Andromeda Galaxy through a variety of instruments ranging from binoculars to large premium Dobsonians.

One of the most memorable was seeing the galaxy from Cherry Springs State Park in 2005 through a homemade 18.5" (yes, 18.5") Dob equipped with a binoviewer capable of low-power views.

On another occasion at CSSP the warp in the backside of M31 was clearly visible through my friend Tony Donnangelo's 20" Starmaster Sky Tracker Dob.

The best view of M31 that I've had through a small aperture was at Stellafane in 2007 before the 13mm Ethos was released. Al Nagler's 127mm Tele Vue apochromatic refractor and the 13mm Ethos produced an incredible wide-field

view of the largest galaxy in the Local Group.

I've also had fun hunting down quite a few of M31's globular clusters through larger apertures.

Hmmm...never tried M31 with a binoviewer...maybe I oughta. ;)

ReplyDeleteA couple of years ago I was trying out a couple of refradtors, a 6 inch achro and a 120mm apo and wanted to compare the view they put up with my 8" SCT. The achro's view was comparable to the SCT, meaning about all I could see from my orange zone drive was the bright nucleus. But when I turned the apo on M31 I gasped. The nucleus was much brighter in the smaller aperture scope and I could see the arms of the galaxy spiraling outward. That view along with superior views of M27 some other things convinced me to keep the apo refractor. Before with the SCT M31 just wasn't anything I was interested in looking at because it wasn't that impressive. But it is very impressive in the refractor as is M42 and so many other objects that I previously thought were mediocre.

ReplyDelete