And I do, muchachos, I do. “But Unk, the Moon is shining bright over Possum Swamp right now, just as she always has.” Well, yeah, but that don’t mean I’ve paid requisite attention to her. During the years of the Herschel Project, all Luna was was an annoyance, her shining face getting in the way of my quest for ever dimmer and more distant galaxies. When the Project ended, I cast about for a new observing project, trying out everything except our neighbor without success.

Slowly, ever so slowly, I came to believe my next observing

interest would be something with a little more form and substance than yet another quest for “small, dim, slightly elongated” PGC sprites. This looking for a new

something to look at also coincided with my retirement, which I struggled with

and which had left me less than willing to haul out big telescopes to look at anything.

Then, in 2019, I suffered a near-fatal accident that temporarily rendered me

unable to set up anything but the smallest telescopes. And left me permanently

unable to deal with the largest ones.

During that time, I found I wanted to look at something,

though. Anything. Something-anything just spelled, yes, good old Hecate.

As I related some time back, when I was a kid I knew the face of the Moon, her

mountains and craters, as well as I knew Mama and Daddy’s subdivision, Canterbury

Heights. But I let that slip away over the course of long years of deep sky

voyaging. I came to regret that, and decided I wanted to go home to the Moon

I missed.

|

| Eloise |

You know, I’ve been thinking a lot about that charm, and

found there is another way I miss the Moon. I miss the old Moon. The Moon

of Chesley Bonestell and Men Into Space.

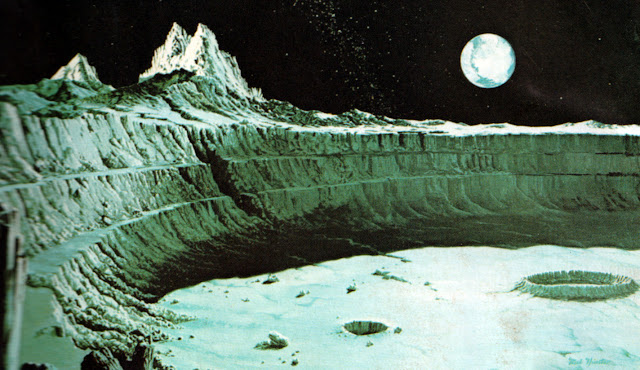

A Moon of mystery, a Moon of razor-sharp peaks and crater walls. A Moon

where almost anything might happen. Oh, even when Unk was a sprout we knew Luna

was probably lifeless. But, still, who knew what strange things might lurk there?

I missed that old Moon, but it turns out she is still with

us. Yes, the landscape is a gentler one than that depicted above in an illustration from Doubleday’s old book The Moon (from their Science Service series),

but the mystery is still there. As I came to realize watching the recent

Artemis mission, the prelude to a new age of lunar exploration, we still don’t

know pea-turkey about the Moon. Not really.

Despite centuries of observation with telescopes, decades of

examination with spacecraft, and all too few years of manned exploration, we

haven’t even scratched the surface of our neighbor and friend. What might we

find up there? Who knows? Contemplating that, I grabbed a handy

telescope and got out under a just-before-First Quarter Moon.

Before I tell you what I saw on a gentle April evening in

the Swamp, though, maybe a word or two about the instruments I’ve used to explore

the Moon. I began with a cheap set of plastic binoculars from the toy department of our local discount store ‘round

about 1960 or so.

These were humble glasses to be sure, though they did,

unlike what you’ll likely find in toy departments these days, feature glass

lenses. Likely they weren’t really binoculars, so to speak, but actually

two Galilean telescopes side by side. But you know what? They showed, just

barely, CRATERS to little Rod’s amazed eyes when he thought to turn them

on the Moon (said glasses having been bought to use while playing Army).

|

| VMA 8.0... |

Flash forward five years to my first telescope, a 3-inch

Tasco reflector. It really wasn’t much of a scope, being far inferior to most

of today’s similar instruments. I never could make out the rings of Saturn I

longed to see. The little thing did do a workmanlike job on the Moon, though.

Not just good enough to allow me to begin to begin finding my way across the

Moon’s labyrinthine surface, but to actually try taking pictures with my little

Argus box camera.

But what finally gave me the Moon? My 4.25-inch Edmund

Scientific Palomar Junior. Let me say this:

In lunar observing, more aperture is always better, always. But a

3 – 6-inch telescope is more than adequate—MORE than—for showing you the basic

wonders of the Moon, and to allow you to do as I did as a 12-year-old, learn

her surface (with the aid of the Moon Map in a long-ago edition of Norton’s

Star Atlas).

Of course, I went on to the bigger and better…a 6-inch Newtonian,

8-inch and larger SCTs, bigger and bigger reflectors, computer-controlled

electronic cameras, etc., etc., etc. Today? I am back to, yeah, 3 – 6-inch

telescopes. They show me what I want to see and they let me relax and enjoy it.

Imaging the surface of the Moon in detail with a big CAT and a camera was fun,

but the act of doing so always seemed a challenge, a test. Could

I succeed in bringing home images? Now I just bask in Luna’s silv’ry glow and

marvel at her, not unlike all those nights when I stared open-mouthed with that

3-inch Tasco.

|

| Unk's first Moon picture, 1965... |

Anyhow, I grabbed the 3-inch, Eloise by name (who has been

with me—GOSH!—for about a dozen years now), and headed for the back 40 just

after the passage of a rather violent storm front the day before. “Grabbed”? I

was abashed to realize “grabbed” wasn’t the proper word. Maybe “lugged.” As Unk

prepares to embark on his 70th trip around Sol in a few months, it

appears the 80mm refractor and “light” alt-az mount have put on weight! It was enough of a struggle getting Eloise and

the AZ-4 out the back door I decided to do it in two trips next time. Out back,

finally, I didn’t expect much. The Clear Sky Charts were predicting clear and

clean skies, yeah, but, in the wake of a front, as you might expect, seeing

would be so-so at best.

With Eloise out in the driveway, how was it once dusk had come

and gone? No, seeing wasn’t great, just as predicted, but it wasn’t that

bad. Luna looked pretty steady in the 3-inch. That’s one of the benefits of

smaller aperture: you are looking up through

a smaller column of air, and the wiggles are less obvious. Funny thing, though?

Used to be on a somewhat brisk, seeing-disturbed night we could expect crystal

clarity. Not of late. There was substantial haze the front hadn’t cleared out. The

reverse is also all-too-true now. On a hazy, humid night, we’d normally have

very steady seeing. Not anymore.

Anyhoo, I inserted one of my favorite 1.25-inch eyepieces in

the diagonal, a 16mm Konig I’ve had for 30 years (it was the first wide field

eyepiece more sophisticated than an Erfle I owned). Focused up at 57x, and had

a cruise up and down the terminator. Despite the haze, Diana was beautifully

sharp, being just past culmination. But where would I plunk down? Which area of

Selene would I concentrate on? My rusty knowledge of Lunar geography impelled

me to focus on the northern highlands rather than the crowded southern expanses.

What there was above all was Plato, the great walled plain, a dark lava-floored crater that extends about 100 miles. Foreshortening makes Plato look strongly oval, but it is actually round. What’s to see there? The game I’ve always played is “find the craterlets,” the tiny craters (a couple of miles across or thereabouts) that litter the floor. Replacing the Konig with a 6mm Plössl (151x) showed strong hints of ‘em, though, as you might expect, 150x is about where a 3-incher’s images begin to dim. But some of the little guys were not that difficult with Plato near the terminator on this evening.

|

| VMA has pictures aplenty! |

Most beautiful aspect of this giant, however? The shadow of its rough, mountainous western rim. It hearkened back to that vision of the old days, those razor-sharp peaks. The shadows of Plato’s walls, which are relatively gentle in reality, looked just like something out of a Bonestell painting.

Next? To the south of Plato is another huge walled plain, Archimedes,

which is about half the size of Plato, but in other ways much like it, sporting

a dark floor and its own gang of craterlets. For some reason, lunar observers

tend to talk less about this amazing feature than Plato, but it is well worth

study.

As are the two great craters east of Archimedes, Aristillus

(34 mi.) and Autolycus (24 mi.). These are more normal looking craters

than the two walled plains, with Aristillus sporting an interesting and intricate

central peak and terraced walls. Autolycus is without a central peak but there

is still plenty of floor detail to pour over.

I didn’t really want to cross the lunar Apennine mountains,

so I turned back north, touching down on another pair of exceedingly prominent

craters, big Aristoteles (54 mi.) and Eudoxus (42 mi.). The former looks much like the walled plains

we visited earlier, but it doesn’t quite have the “plain.” Its floor has not

been completely covered with lava. There are numerous hummocks in the middle,

the remains of central peaks not drowned in lava. There is also wall terracing and other details

that invite exploration. Eudoxus? Heavily terraced and intricately detailed

walls will catch your eye in any telescope.

I thought I’d head over to the Alpine Valley next to see

what I could see. After that, maybe a stop at that fascinating crater, Cassini?

Uh-uh. Nosir buddy. Urania had other ideas and just as I finished exploring Eudoxus,

she covered her sky with more haze that in minutes devolved into clouds.

But that was OK. I’d seen a lot. And while Eloise was

definitely not as easy to haul around as Unk remembered, it was the work of but

a few minutes before your correspondent had put Eloise to bed and was sampling the

waters of Lethe (which come from a Rebel Yell bottle) while watching TV with

the cats.

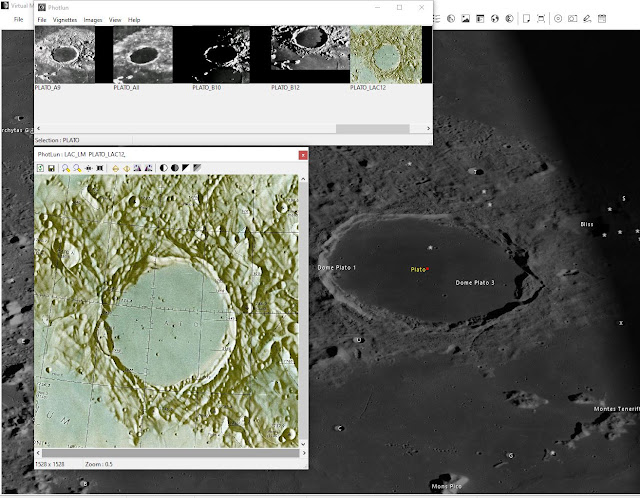

Before leaving you this morning, let me insert a plug for Virtual Moon Atlas, which I’ve mentioned here a time

or two. I was embarrassed to discover I was a couple of versions behind and promptly downloaded and installed the current one, version 8.0, the 20th anniversary

edition (hard as that is to believe).

Sure glad I did. More “textures” than ever, including one

from the famous Lunar Aeronautical charts I love so much. Oh, and something you

will find useful for deep sky observing, too, “Calclun,” which at a glance will

show you lunar phases over the course of a year or give you details for a

single night. Go get it, muchachos—it’s still free!

“THE MOON AND YOU” (LeRoy Shield)

We all love the Moon. Good that you have found your way back to basics.

ReplyDeleteThe telescope weight has little to do with age. I know because I'm also heading down the ramp towards 70.

It's the back that doesn't want to carry big scopes.

And you solve that by getting yourself a permanent observatory in the backyard. This is how I solved it myself...

Lars

If you're looking for a challenge on the moon, I found/documented a "new lunar feature". See ALPO write up here.https://alpo-astronomy.org/gallery3/index.php/Lunar/The-Lunar-Observer/2016/tlo201609

ReplyDeletepage 19 -ish .

Ken