Sunday, February 22, 2015

Down Chiefland Way: Brrr!

As I said last Sunday, muchachos, I was loath to give up my planned February dark of the Moon CAV observing run for any reason. Even predicted historic low temperatures that just kept getting lower. I even stuck to my resolution to tent camp on the field. How did I do with that and everything else? All shall be revealed next week. For now, I am just trying to WARM UP!

Nota Bene: Thanks to the vagaries of Blogger.com, the post referred to above has fallen out of the archive as posts occasionally do. To read about this Uncle Rod Adventure Down Chiefland Way, you'll have to go HERE.

Next Time: A Long Time Ago...

Next Time: A Long Time Ago...

Sunday, February 15, 2015

The Return of the King

|

| The King is in the building, ladies and gentlemen... |

I’d be heading down to the Chiefland Astronomy Village for

the February dark of the Moon run, sucking up deep sky photons with my cameras, but before that, I planned to stay closer to home, a mere 4.8

AUs away from our cozy little rock, out in the realm of the frighteningly

magnificent 5th world.

Not that I expected much for my efforts. I mean, come on boys and girls, it’s freaking February.

Even down here on the (sometimes) sunny Gulf Coast where we are usually at

least a little out of the path of the Jet Stream, the good seeing, the

atmospheric steadiness, you need for high resolution planetary imaging or

exacting visual work isn't a regular feature of winter.

Despite the likely prospect of a misshapen Jupiter dancing

and shimmering in cold winter air, I figured I’d devote last Sunday evening to

a little visual scoping out of Jupe to get me back in the mood for planetary

work. Being lazy, the telescope I’d use for that would be my beloved Celestron

C102 refractor, Amelia. I lugged her and her AZ-4 mount into the backyard at

dark. It would be about an hour and a half till my quarry was up high enough to

bother with, so to amuse myself while waiting, I thought I’d have a look at Venus low in the west. In went the 8mm Ethos, to

the planet we went, and… “Ulp!”

I expected a fair amount of false color, folks. Even at f/10,

it’s asking a lot for an achromat to throw up a decent image of Venus at 150x

and above. And, yes, there was plenty of the dread color purple. But, you know,

it really wouldn’t have been bad if the cotton-picking planet had stayed still. When the atmosphere

steadied down occasionally and briefly, a surprisingly sharp gibbous disk was

visible. Unfortunately, that didn't happen much. The seeing was, no denying it,

as your Uncle likes to say, “punk.”

Just for spits and giggles (this is a family-friendly blog, y’all) I moved the telescope to Sirius. I

habitually check the star whenever I have a scope set up to see if I might spy

the Pup, the Dog Star’s white dwarf companion. Not a prayer. The story was the

same as with Venus. The color wasn't bad, and the star threw up a nice Airy

disk and diffraction rings once in a while, but not often. Mostly Sirius was a

boiling mess. It began to look as if I'd be wasting my time with Jupiter.

I was still hoping, though. I'd leave the C102 outside for the hour required for Jupe to hit 30-degrees.

If he looked as bad then as his sister world had, I’d go back in again, have some drinks and TV,

and try again in another hour after that.

Back in the New Manse's cozy den, in addition to surfing the cable channels, I spent some time mulling over (I seem to do an awful lot of that about an awful lot of things lately) my history with Jupiter, our friendly, neighborhood gas giant.

Back in the New Manse's cozy den, in addition to surfing the cable channels, I spent some time mulling over (I seem to do an awful lot of that about an awful lot of things lately) my history with Jupiter, our friendly, neighborhood gas giant.

|

| My Pal... |

Let’s dispense with me and Jupiter in the 1960s right off

the bat. I never did see much of the planet with my 4-inch Palomar Junior

reflector. Oh, I loved the shuttling Galilean Moons, and I could make out the

north and south equatorial belts, but that was about it. I wanted to see the

Great Red Spot bad, but I am not positive I ever even glimpsed it with my little telescope.

The truth is that for an inexperienced observer, especially one like li'l Rod who

didn't tend to give the planet (or any other object) much eyepiece time before

going on to something else, 4-inches ain't much aperture.

The mid-late 1970s should have been better. I had a C8 and

was working on my impatient nature, not just regarding astronomy but everything

else. The problem for me and Jupiter in the 70s was now that I had a BIG C8 I

was deep sky crazy. Having very dark Arkansas skies at my disposal didn't help;

I didn't care pea-turkey about boring old Jupiter or any of his

Solar System compadres.

Nothing changed, really, till the late 1980s. I was back in

the Swamp and living under light polluted skies (not far, interestingly, from

the Garden District and the old Chaos Manor South). You can see many deep sky

objects from a light-polluted backyard—hell, I wrote a whole book about that a

few years ago—and I was going through a period when, for a variety of reasons,

I was doing a lot of observing. Those

quiet moments under the stars were like a tonic for me.

If there was a Moon in the sky, or it was hazy, or there

wasn’t much I wanted to look at deep sky-wise in my badly compromised back 40,

I’d turn back to the Solar system, and, especially, to Jupiter when he was on

display. Saturn is cool, and will give up some disk detail. Same with Mars. But

neither offer the regular wealth of detail Jupiter is capable of showing.

Under good conditions, a C8 can deliver incredible amount of

detail on Jupe. Especially if you’ve learned to be patient and keep looking. I

had, and the Great Red Spot was no longer a challenge. Two cloud bands? That

was just the beginning. This was the

stuff I always longed to see, and the irony was that it wasn’t even that hard

with just a little more aperture and a little more patience. In fact, when I kept the patience but gave up

the larger aperture, I was still able to see a lot of Jove.

As my second marriage foundered, it eventuated that I needed

to sell my C8. Which was OK; I just wasn’t that distressed about letting it go. As I’ve

written before, the Super C8 Plus that replaced my (excellent) Super C8 wasn’t exactly

a barnburner. Anyhow, I suddenly found myself back with the freaking Palomar

Junior.

I was hoping that, given my better eyepieces and much better

skills compared to what I'd had in the late 1960s, the wee scope would show me more

of Jupiter than it had when I was a sprout. It did, but not that much more. The truth is that a

6-inch reflector or a 4-inch refractor is just better on Jove. Shortly, I was

able to up my game a mite with a 6-inch home brew Dobsonian, and, as expected, the

planet got better again. Not C8 better,

but better. That old saw, “aperture always wins,” is every bit as true for

seeing planetary detail as for seeing dim galaxies.

Still, I was able to pull some detail out with my 6er, as a page of my

logbook from that era shows (all my logs from the 60s and 70s were lost, but I

still have some from the 80s and early 90s). I usually couldn't see fine detail, not convincingly,

with the 6-inch, but I was seeing enough to keep me looking.

Actually, I didn't get my first really good look at the planet until 1994. As I've recounted a time

or three, the Saturday of my first date with the wonderful Dorothy, I’d got on

the telephone, called Astronomics, and ordered a 12-inch Meade StarFinder

Dobsonian, the now-famous “Old Betsy.” She didn’t arrive until the day before we

were wed in September, so First Light was understandably delayed. As soon as we

got back from our Virginia honeymoon, however, I manhandled the scope’s enormous

white Sonotube into Chaos Manor South’s backyard for a look at Jupiter.

Betsy was just an inexpensive Dobsonian, an f/4.8 Dobsonian,

so I didn't expect much planetary performance from her, but there was a bright full

Moon in the sky and there was Jupiter, so why not? Not only was I not sure of

my scope, the planet was getting awfully low in the west. Nevertheless, in went

my vaunted Circle T Ortho and…

Oh. My. Freaking. God. There

was all the detail Patrick Moore told me (well, in his books) I might see some

day. Belts? There were belts and belts and belts and zones and zones and zones.

There were loops and whorls of clouds. There were spots. There were Festoons.

There was plenty of not very subtle color—blues and browns and yellows and

creams. Oh, and red. Or pink, anyhow. Most of all there was the Great Red Spot.

It was stark despite its somewhat faded character at the time. Hell, I could glimpse

details within the spot.

The 1990s were mostly a deep sky time for me. Those were the

years I got back into astrophotography with a new C8, Celeste, I bought in the

spring of 1995. Those were also the big star party years, with Dorothy and I

taking Old Betsy all the way to the Texas

Star Party to view distant wonders. The

next decade, however, would bring me back to the Solar System. That was no

doubt spurred by all the excitement concerning the 2003 Mars apparition.

|

| Jupiter 1994, SAC 7B... |

Yep, Unk was finally ready for a break from the Great Out

There. Suddenly, the planets were fascinating again. Hell, I rejoined ALPO (the

Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers, not the dog chow) at the 2003 ALCON in Nashville, and by September I had a

hard drive full of mind-blowing Mars pictures thanks to my SAC 7

camera, as I recounted next week. Mars was soon shrinking, but that didn’t mean

I was ready to leave the planetary neighborhood. Jupiter would become available

as spring 2004 came in. What would the SAC do with him?

It turned out Jupiter was actually easier to image than

Mars. Not surprisingly, since the gas giant was larger than Mars had been at its

largest. While Jupiter is, maybe surprisingly for a generation raised on those

crazy-colorful Voyager images, really a world of low contrast, pastel features,

they are still easier to capture than the Martian dark markings. I also found

the planet easier to color-balance. It was hard to convince myself Mars should

be more a peach color than an angry red, but was always clear what Jupe should

look like: somewhere between the mild

cream/brown of the eyepiece and the Technicolor riot of the Voyager shots.

The only diff? Jupiter rotates rapidly enough that too long

an .avi sequence will cause blurring when the frames are stacked. But a minute

or so coupled with our usually good seeing always got me plenty of frames to

play with, even at the pitiful 5 – 15 frames per second the SAC 7 could muster.

I was pleased with my Jupiter pix and planned to keep on imaging the planet

every time he was in the sky.

That’s what I planned, anyhow. I was even a regular

contributor to ALPO for a while, sending in my Jupiter images, good and not so

good, like clockwork. That and my love affair with the Solar System continued

for three-four years till I heard the call of wild intergalactic space again.

2008 found me finally hitting the Herschel 400 HARD, and the next year saw the birth of the Herschel Project. Moon and

planets? Not even on my fraking radar.

Post Herschel Project, I’ve had several observing programs

on the drawing board, and a few that even got onto the observing field a time

or two, notably The Burnham Project, my quest to observe all the Handbook’s

DSOs, and Operation Arp, my tour of Chip Arp’s peculiar galaxies. I’ve also

done more deep sky prime focus imaging than I have in a long time. But I’ve

also regularly been coming home.

Destination Moon, my tour of the lunar surface

has been a lot of fun. And the other night when I was out trying to get some

shots of the terminator and happened to look over my shoulder at old Jupe

rising in the east, I began to think “It’s planet time again.”

|

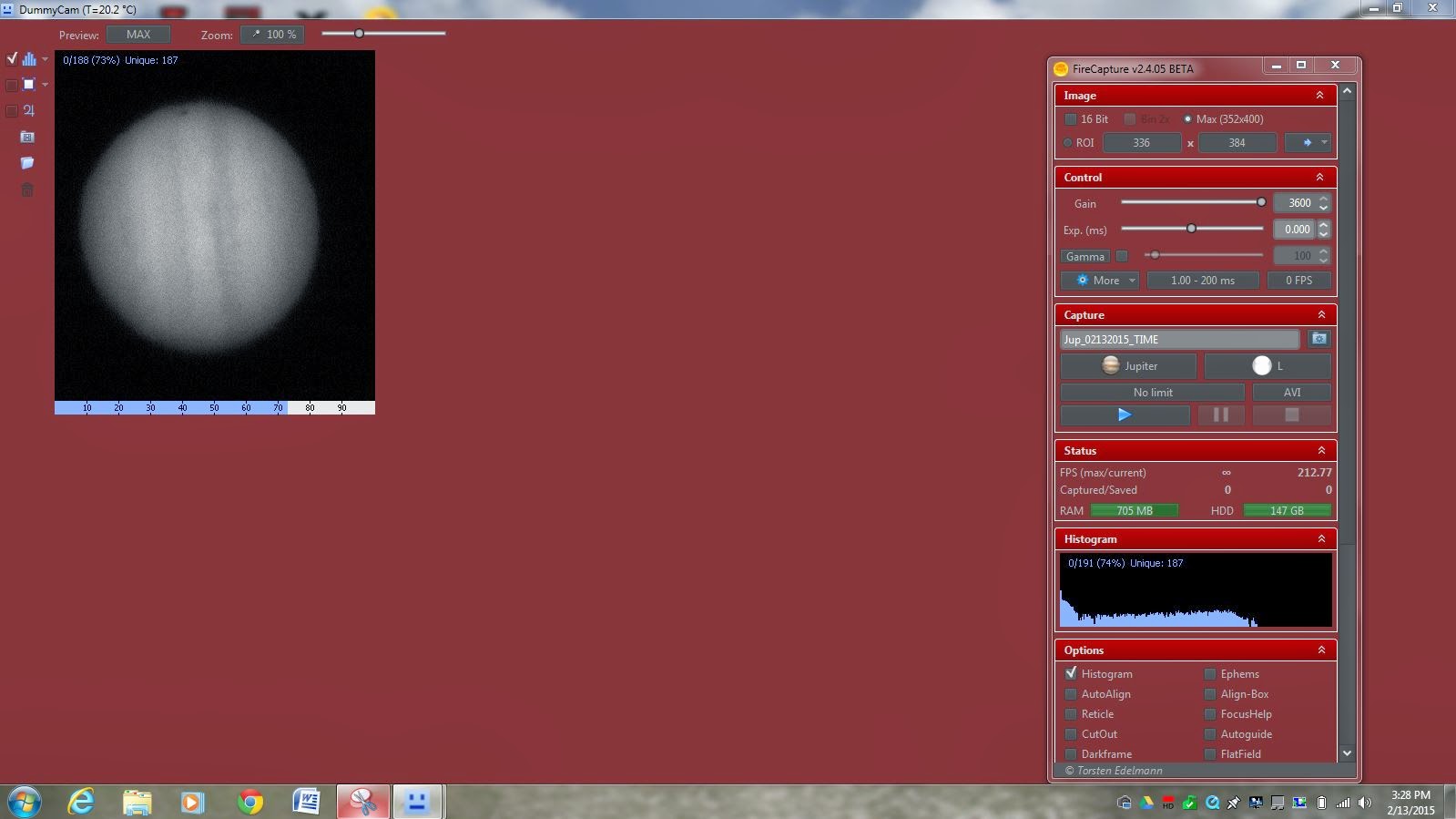

| FireCapture 2.4... |

And so it seems to be, which brings us back around to last Sunday

night. After an hour, I wandered back out and took another look with the

C102 and the 8mm Ethos. The seeing wasn’t that good, but it wasn’t that bad,

either. The flattened disk of Jove was reasonably sharp and not swimming too

much. There wasn’t a wealth of detail, but the equatorial belts were clearer

than they ever were in the old Pal Junior, and the moons were usually pinpoints

rather than smeared out blobs.

As I watched, I occasionally began to pick up more. The Polar

Regions and some narrower belts began to appear at least. It was almost

enough to make me want to run inside and see if I could find my Wratten 80A

filter. But man was the dew heavy. You'd a-thought it was spring already, and the

amount of detail the refractor was delivering wasn’t quite enough to make me want to get soaked to the skin.

Nevertheless, I wanted to see more of Jupiter again. And I knew how to do that.

Or, actually, I knew a couple of ways

to do that: with more horsepower and with a camera.

“More horsepower,” more aperture, was what I had in mind for

Tuesday night. A front had barreled through, one of the last strong cold fronts

of this winter, I hoped, and I didn't think it would be a night for imaging.

The Clear Sky Clock (I just can't get myself to call it “Clear Sky Charts”) agreed. I thought I might set a visual scope out, however,

and take a few looks at the King during the commercials in The Flash and Agent Carter.

Didn't expect much, but I was hoping a bigger scope might do some good on a

poor night.

The telescope of the evening was the lightweight Dobsonian Pat made out of

my old 8-inch Konus (Synta) Newtonian, Old Yeller. In addition to four times the

light gathering power of the 4-inch, the scope would bring much more resolving

power too. That was offset by the fact that that an 8-inch mirror would be

looking up through a larger column of disturbed air than the C102’s 4-inch

objective. Still, I’ve usually found that you eventually see more with more

aperture, even on nights when the atmosphere is reluctant to behave.

I gave the scope plenty of time to cool down, several hours,

and I gave the planet plenty of time to get away from the eastern horizon. I

didn't go back outside until Agent Carter

went off at 9 p.m. Inserted a 7mm Uwan eyepiece (142x), put my planet hungry

eye to the ocular and saw…

|

| Stacked with AutoStakkert... |

Nuttin’ honey.

Well, not quite nothing. There was something, but that something was just a

big, white, flattened Ping-Pong ball with two subdued horizontal stripes, the North and

South Equatorial Belts. I shouldn't have been surprised; the seeing was even

worse than it had been at its worst on Sunday evening. Often a larger scope

will show more than a smaller one on nights like this if you wait for those

brief moments when the atmosphere steadies down, but I wasn't getting any of

those moments. I gave it up as a bad business after a frustrating hour and went

back to the Boob Tube.

Wednesday afternoon, I strolled out onto the deck to see

what I thought the chances for bringing back decent images might be. The Clear

Sky Clock was

predicting so-so seeing at best, but it was warm(er), the air was still, and I

thought there was a chance I wouldn't be wasting my time with a camera.

Even if it turned out conditions were not good enough for

decent images, I still wouldn’t be wasting my time. I wanted to try out the latest

beta release of my favorite planetary image capture program, FireCapture,

anyway. I went ahead and set up old Celeste on the VX mount.

Sunset came, and, after that, a few drinks and Arrow. When the show went off, your

Uncle somewhat unsteadily headed for the backyard. Everything was ready to go

including the laptop on the table on the deck. All I had to do was get the

mount goto aligned and polar aligned. I essayed a 2+4 alignment, went on to the

AllStar polar alignment (Rigel), and declared myself ready to shoot. I could

have done another 2+4 to tighten up goto after the polar alignment, but since

I’d be on Jupiter all night, that really didn’t matter. What did matter? Tracking, since I’d be using

FireCapture’s ROI feature.

What’s they-at? Rather than shooting a full frame, FireCapture, can shoot a cropped area

just large enough to contain a planet (you select your planet from a drop-down

menu), the “Region of Interest.” By downsizing the frame to just what’s needed

to fit a planet, FireCapture can get

the frame rate up, doubling the ZWO ASI120MC camera’s speed from a hair over 30

fps to 70 fps. “More frames” is always good when shooting planets. Especially

on a night like this one when it appeared the seeing would start out average and get worse.

The problem, if there is one, when using the ROI feature?

Your mount has to be tracking well enough to keep the planet in a very small

field for the duration of the exposure. That was not a problem with the VX.

Even at f/20 with the C8, I only had to adjust the mount’s aim occasionally; it

was easy as pie to get 1-minute (and longer) .avi sequences. I gotta tell you,

folks, the humble Celestron mount continues to amaze me with its inexpensive

goodness.

Anyhow, I centered Jupiter in the flip mirror on the back of

the C8—a flip mirror is necessary

for high resolution/large image scale planetary photography if you want to keep

your hairline intact—and cranked up FireCapture

2.4. What’s new in the beta? Most noticeably, a completely redone and modernized user

interface with a control window separate from the preview window. Other than

the fancy new GUI, I was pleased to see everything worked purty much as it

always has—which is “very well.”

|

| Stacked with Registax... |

How was the planet looking? When I got Jupiter focused up

with the JMI motofocus, I had to admit “not too

shabby.” Oh, it wasn’t like it can be on those rock-steady spring nights when it just sits there, maybe

wavering/fluttering a little every once in a while. Still, not bad. Watching

the preview frames flying by, I could make out more than just the two main

cloud belts.

I sat out there on the deck in the chilly but not cold air for

the next hour or so firing off .avi sequences of the Big Boy. I tried to get

about 2000 frames every time, which took around 30-seconds - 1-minute depending

on my exposure settings. As always, I aimed for a Jupiter that looked just

slightly underexposed to my eye. Most of the time, I thought I was getting OK

data, but as nine p.m. approached, I could tell, ironically, that the seeing

was degrading. Why ironically? Because it was just as the planet was getting

nice and high that the atmosphere went totally to hell.

I shut down, gathered up the laptop, and left the scope set

up under a Desert Storm cover in case I wanted to give it another go Thursday night.

That would depend both on my results when I processed Wednesday evening's

sequences and what the weather did. Thursday was predicted to be about the same

as Wednesday seeing-wise. Unfortunately, that prediction turned out to be wrong,

and another blasted cold front came roaring through Thursday afternoon,

scotching the idea of more imaging.

Processing the Thursday morning was surprisingly easy; the data

I got was considerably better than I thought it would be. Stacked the frames of

the .avi files with Registax 6 (and AutoStakkert, which I am learning to use),

applied the program’s amazing wavelet filters, did a little tweaking in Photoshop, and that was all it took,

muchachos. Hell, not bad, not bad at

all. Which just goes to show the truth of that old saw, “Nothing ventured,

nothing gained.” It would have been easy to plunk myself down in front of the

television Wednesday evening and stay there. Sure am glad I didn't.

Next Time: Down Chiefland Way…

Note: I’ve been informed that long-time

astro-businessman Jeff Goldstein of

AstroGizmos has passed away. I’d just seen Jeff at the 2014

Deep South Regional Stargaze, and, once again, having a source of those little

things, from batteries to dew heaters, that you unexpectedly need at a star

party came in so handy. Jeff was friendly and helpful and will be

missed. I have not heard whether the business will continue…

Sunday, February 08, 2015

Big Time

What would be the subject of this week’s blog? That was kinda hard. I have not, as I

feared when I took this weekly, run out of things to say, muchachos, but sometimes a topic doesn't immediately suggest itself. Those “sometimes” usually being

the times when not much is going on around here astronomically.

Following my last minute comet-save recounted last week, I

thought I’d so some Moon pictures for another installment of my Destination Moon project. I still had

the C11, Big Bertha, set up in the backyard following my abortive try for

asteroid 2004 BL86. Alas, the seeing was just not good enough. Even given my

humble standards, not a single image was usable. OK, I’d back off to a more

forgiving C8 the next evening. Nope. The .avis I got with my 8-incher, Celeste,

were better but not better enough. Into the recycle bin they went.

Should I go RSpecing again? I’ve promised myself I will re-familiarize

myself with RSpec, that wonderful spectroscopy software. Unfortunately, the seeing was

still bad enough following my failed lunar voyages to suggest I would be

wasting my time. Couldn't even do any visual observing, since clouds and rain were

now moving back in. Astronomical road-trips? I would be heading down to the Chiefland

Astronomy Village next dark of the Moon, but that was still weeks away.

I thunk and I thunk and I thunk, but I was stumped. Till one

afternoon I was hunting something or other out in the Shop. I opened a cabinet,

pulled out a box, looked in, and what should I see but my first real planetary

camera, the good, old SAC 7B. Which brought to mind my adventures with that

humble CCD—which I have talked about here before—but even moreso, it reminded

me of all the fun I had during the great

Mars opposition of 2003, something I haven’t talked with y’all about at

length.

By 2003, Unk had been observing Mars in decidedly on-again,

off-again fashion for over three decades. I’d been at least trying to see the planet since 1965. Mars,

maybe even more than Saturn, was the world young Rod, like other space-crazy

kids in the 1960s, wanted to see with his own eyes. Even when I was the

greenest of greenhorns, I knew that most of the time Mars was nothing more than

a subdued orangish star-like object. However, I also knew there were times,

“oppositions,” when the planet was close to us, when Mars showed his mysterious

face to Earthlings and their puny telescopes.

Even though Mars was at opposition the spring I got my first

telescope, a 3-inch Tasco Newtonian, I don’t believe I saw him then. I knew

Mars was visible and putting on some kind of a show since, in them days, our newspaper, The Mobile Press, carried occasional little filler-blurbs related to “space,” and I’d

read one that mentioned Mars was once again close to Earth. But I had no idea

how to find him. My first issue of Sky &

Telescope had yet to arrive, and my only resource was my copy of the Little Golden

Guide, Stars,

which, while it had some planetary tables and gave the constellation Mars was

sailing through that April, Leo, it didn't pin down the planet’s exact position.

I did look around for Mars in Leo's area occasionally, but

none of the stars looked as obviously different to my naked eye as I thought

Mars should. Certainly nothing I got in my low power eyepiece looked like

anything but a pinpoint (it’s likely I actually did see Mars but mistook him for a bright star). In retrospect, I didn’t

miss much. Mars was small, 14”, that opposition, and would have been a tiny,

featureless b-b in my somewhat putrid little scope.

The next opposition of Mars was in April of 1967, and he was

better, but only a little better,

15.5”. This was the first one I was there for. Not only did I have a mucho

bettero telescope, my 4.25-inch Palomar Junior

reflector, which, if not exactly a planetary powerhouse due to its small

aperture, did deliver sharp images with its f/10 (actually closer to f/11)

spherical primary mirror. Also, I had learned to find stuff in the sky. The

epiphany arriving in December of 1965, when, just after taking my first look at

M42, I captured M78 by star-hopping to it—not that I knew what I was doing was

called “star-hopping” (which term may not even have been in use at then). And I had Sky & Telescope to guide me.

I’d educated myself about Mars as well as I could. Not just

with the trashy sci-fi movies like The Angry Red Planet

I saw down at the Roxy Theatre, but with Patrick Moore’s books. I tried to take Patrick’s

cautionary words in The Amateur

Astronomer to heart and not expect too much: “When you first look at Mars through a

telescope, you…may…feel a sensation of anticlimax. Instead of a globe streaked

with canals and blue green vegetation, you may…make out nothing but a tiny red

disk.”

I comprehended that Mars was small and far, far away even

when closest to Earth, but, still, this was MARS. There must be more to it than just Patrick’s

small, red disk. To be honest, what stuck in my mind from the above quote was

not “small, red, disk” but “canals and

blue green vegetation,” the very things my astronomy mentor was warning me

not to expect.

So, one warm spring night I finally tracked down the

mysterious fourth planet. Amazingly, it wasn’t even hard. Even if I hadn’t done

a pretty good job or learning the constellations since that wonderful morning

when the Old Man had walked into my room bearing the Tasco—I even knew subdued Virgo where the planet was now hanging out —more experienced me

couldn’t have missed it. Even though this was an average opposition at best,

there was Mars just burning up the sky, looking like a baleful red eye gazing

down at the Rodster.

So, one warm spring night I finally tracked down the

mysterious fourth planet. Amazingly, it wasn’t even hard. Even if I hadn’t done

a pretty good job or learning the constellations since that wonderful morning

when the Old Man had walked into my room bearing the Tasco—I even knew subdued Virgo where the planet was now hanging out —more experienced me

couldn’t have missed it. Even though this was an average opposition at best,

there was Mars just burning up the sky, looking like a baleful red eye gazing

down at the Rodster.

If only the view in the Pal Junior had lived up the promise

of the planet’s naked eye appearance. It didn’t, of course. Not surprisingly,

Patrick Moore was right on the freaking money. There were neither razor thin

canals nor mysterious forests in view. It was just that damned tiny red ball.

As I stared into my ½-inch Ramsden eyepiece, which delivered a magnification of

96x, I thought I caught the barest

hint of a polar ice cap. But I wasn’t sure.

My big mistake? I didn’t take Patrick’s other words seriously. In

addition to warning that I wouldn’t see imaginary canals and forests, he

went on reassuringly to say that, with experience, I would be able to make out not

just that polar cap, but also fascinating dark areas and more. I wasn’t

convinced. I looked at Mars briefly a couple more times that opposition and

that was it. Frankly, young Unk was not big on patience and

perseverance. It would take another decade and some hard knocks

before I learned better. I filed Mars away as a bust, and went back to trying

to see Messier objects.

Was I disappointed? Sort of, but not really surprised. Beyond

Patrick’s cautions, the photograph of Mars in my dog-eared copy of The New Handbook of the Heavens

suggested I might not see much of anything. Though taken with the giant Yerkes

refractor, the picture (excellent for the day) was disturbingly blurry.

|

| Yerkes Mars... |

Nothing much changed till 1995. My life was more settled

and happy than it had been in a long time with Miss Dorothy at my side, and I had the biggest telescope I’d

ever owned, Old Betsy, a 12.5-inch Dobsonian. Betsy, in addition to pulling a

lot of surprisingly faint stuff out of our bright Garden District sky, was,

biggest surprise of all, something of a planetary

powerhouse with an excellent primary mirror despite its humble Meade pedigree.

The most important thing in helping me begin to see Mars,

though, was the patience and

perseverance I’d been able to develop (finally). When I first got Betsy, I

began spending hours with Jupiter, trying many different magnifications and using

different colored filters. I saw more of the King of the Solar System than I

ever had in my life. Might the same things work with Mars?

The 1995 opposition wasn’t much of one. At a maximum size of

13.8 arc seconds, the angry one was about a quarter the size of Jupiter’s

average diameter. That didn’t stop me. Seeing detail wasn’t easy. I had to wait

for Mars to get as high as he could, and I had to wait for particularly stable

February nights (a problem even on the Gulf Coast) so I could use high power,

but from the get-go I was scoring coups. First night out, there was Syrtis

Major, clear as a bell. Oh, and the polar cap was putting Unk’s eye out; how

had I ever found it difficult?

I continued night after night, sometimes seeing new

features, sometimes being thwarted by clouds or seeing. But I almost always saw

something. The one thing I never did

do, though? Photograph the planet. Given that my (film) images of much easier

Jupiter resembled custard pies—at best—I figured I’d be wasting my time. Two

things changed my mind about that over the following eight years: the promise

of the 2003 opposition, when Mars would be bigger than he’d been for centuries

or would be again for centuries, and the coming of electronic photography.

I continued night after night, sometimes seeing new

features, sometimes being thwarted by clouds or seeing. But I almost always saw

something. The one thing I never did

do, though? Photograph the planet. Given that my (film) images of much easier

Jupiter resembled custard pies—at best—I figured I’d be wasting my time. Two

things changed my mind about that over the following eight years: the promise

of the 2003 opposition, when Mars would be bigger than he’d been for centuries

or would be again for centuries, and the coming of electronic photography.

As ought-three approached, I assumed I’d be doing my Mars

picture taking with my first CCD camera, a Starlight Xpress MX516. It had done

a pretty good job on Jupiter. Hell, it had bettered my film images by a long

shot, and was a considerable improvement over my camcorder experiments (the camcorder results were pitiful).

The MX516 probably would have done a respectable job on

Mars, but as 2003 got underway, I decided I wasn’t happy with the camera. There

were several reasons for that, but the foremost one was that it wasn't color.

To me, the planets cry out for color. I decided I’d sell the camera on

Astromart and search for the elusive more better gooder, which I at first

thought was Starlight Xpress color CCD cam, the MX7C.

Soon, however, I learned that More Better Gooder for the

Solar System was not another CCD camera. No, the path to Solar System success,

it seemed, lay on another path. The webcam path. By 2003, amateurs had learned

that webcams, the little USB video cameras used for video conferencing (and other

somewhat less savory things) on the Internet were the way to go. Take an .avi

movie of a planet, use software to select the best frames out of hundreds or thousands,

stack those frames into a final image with this new program, Registax, and you had planetary and

lunar images easily better than the best pro Solar System photos of the decade

before.

|

| The SAC7b arrived just in time for Mars--it really was a good little camera! |

I’ve talked a little about SAC Imaging here

before, but only a little. Frankly, I don’t know

that much and I am not sure how much more than what I do know there is to tell,

anyhow. The gist? This is the story as it’s been told to me. I’d welcome

corrections from y’all.

“SAC” does not stand for “Strategic Air Command,” Unk’s old

outfit. It is “Sonfest Astronomical Cameras.” Wha? Apparently a dude down in Melbourne,

Florida, Bill Snyder, had a business promoting Christian music concerts,

“Son-fest Promotions.” He was also apparently very interested in astronomy, and

decided to begin selling astronomical CCD cameras.

Well, sorta. In the beginning, they were CCD cameras only in

the sense that back in the early years of this century most webcams had (small)

CCD chips rather than CMOS sensors. The SACs were humble things, just Logitech

Quickcams that were repackaged in more robust bodies and equipped with 1.25-inch

nosepieces for insertion in a focuser or Barlow. Yeah, “humble” is the word, but the

SAC cams hit the marketplace at the perfect time, just as amateurs were discovering

how good webcams were for imaging the Solar System—how amazing they were for that task.

Snyder didn’t stand still. When he met with some success, he

began offering upgraded and more interesting cameras. Initially, that was the

SAC 7B, which featured a Peltier cooler and was modified to yield long

exposures so it could (supposedly) image the deep sky as well as the planets.

The SAC 7B was remarkably popular, enabling SAC to do the

SAC 8, a more or less genuine CCD camera capable of real deep sky work. The SAC

7B was simply too noisy to be much good there, though its long exposure mode

was useful for imaging Uranus, Neptune, Pluto, and the dimmer moons of the

outer worlds. The SAC 8 was followed by the SAC 10 (designed in part by CCD

Labs’ Bill Behrens). CCD/imaging software guru Craig Stark also had a hand in the

project. The 10, with its, for the time, very impressive 3.3 megapixel sensor, was

supposed to land SAC in the big-time of CCD imaging. Then, suddenly, the SAC story

ended.

|

| Did I ever dream I'd get Mars images like this? NO. |

What happened? As is sometimes the case, apparently too much

success rather than too little killed SAC. The owner made a deal with Orion

(Telescope and Binocular Center) to furnish what was essentially the SAC 8 with

an Orion nametag on it. Alas, Mr. Snyder couldn’t produce enough cameras to

keep up with demand from Orion. He also couldn’t produce the SAC 10 cameras in

numbers large enough to satisfy orders. QA problems also began to mount. Things

spun out of control and SAC crashed. As far as I know, Snyder went back to his

primary business—which was neither concert promoting nor camera building, but,

I’ve been told, managing a Florida motel.

I am still sorry SAC is gone. Bill Snyder had some great

ideas, hired some great people, and I believe that if he’d been able to stay in

business there’d be far more choices in the low-medium price CCD arena than there

are today (i.e. very few). Anyhow, SAC was great while it lasted, and Mr.

Snyder was responsible for me getting the Mars images of a lifetime.

As soon as I heard about the SAC 7B, I knew it was for me.

It produced 640x480 images, larger than those of my Starlight Xpress cam and twice the size of my Quickcam’s, had that cooler

and the long exposure mod in case I wanted to experiment with longer exposures,

and was ready to go out of the box. No hot gluing a 35mm film canister on the

front of the camera to serve as a nosepiece like we used to do with webcams. In

retrospect, I could have probably just bought the less expensive SAC 7 (no “B”), the air-cooled (no Peltier)

version of the camera, and I was tempted to do that, but I’d sold my MX516 for

a decent price on Astromart, so I figured I’d get the top of the line SAC. I

gave Mr. Snyder my credit card number.

I ordered in early spring, and after a couple of weeks of no

camera appearing on Chaos Manor South’s front porch, I began to sweat. The

planet would be getting big soon, and now I didn't even have that dadgum

Starlight Xpress to use on it. I understood Bill probably built cameras as

orders were received, so I tried to be patient. Finally I couldn’t stand it anymore

and fired off an email. The response was rapid, assuring me I’d soon have my

SAC.

|

| One of my first Mars images with C8 and SAC 7. |

When it arrived, I was fairly impressed. No, the build

quality wasn't comparable to the machined beauty of the MX516, but it was

alright. Robust enough (tin-can-like) metal body. Good hefty cables for USB,

Peltier power, and the long exposure interface. The power supply provided for

the cooler was impressive in its capacity. It was undoubtedly just a surplus PC

switching power supply, but it was in a nice plastic box and had a cigarette

lighter output (all these years later I still use it for various things).

The only think I didn’t like about the camera was the

included software, AstroVideo. It appeared to be capable, but not very user

friendly, and you know how I am about that. No problemo. My astro-BBS surfing

had turned up a program many webcammers were using, K3CCD Tools. It did almost as

much as AstroVideo, but in a less

convoluted fashion. Today, it has been surpassed by programs like FireCapture, of course, but even now it is still somewhat usable. After playing with an evaluation copy, I handed over my bucks for K3CCD

right quick. With the software in place, it looked like we was ready to go.

The opposition itself was almost anticlimactic because it

went so smoothly. The weather usually cooperated, and my friend Pat and I were

able to live up to our vow to take advantage of every second of Mars. It was a

wild time if you were an amateur astronomer. We were all obsessed by Mars; some

of us even moreso than others. I was a speaker at ALCON 2003 in Nashville, and hated to give up a few nights of the planet in

July. I did, however, and had a good time. Others were not so willing to part

with the Old Red for even a little while. Legendary planetary imager Don Parker flew in, gave his talk, and

flew right back out to get at Mars again that night.

Every clear evening, and there were plenty of them, I’d set

up one of my three driven scopes in Chaos Manor South's backyard. Often that was Celestron Ultima 8, Celeste (then

still on her non-goto fork). I also used the 8-inch Konus (Synta) f/5 Newtonian

I'd bought to help do some of the observing for my book, The Urban Astronomer’s Guide. When I needed horsepower, it was my new NexStar

11, Big Bertha. Even with our often good

seeing, however, the focal length of the 11 tended to be a bit much most of the

time. The Konus, in contrast, was too short and was mainly useful when the

seeing was punk. The C8? As C8s always are, it was JUST RIGHT.

I did a little “just looking” with eyepieces on some nights,

but mostly my game was pictures of Mars. Initially, I wasn’t

sure how good they’d be, but I found out in a right quick hurry. On the very

first evening with the camera in a 2x Barlow plugged into the visual back of

the C8, Mars was surprisingly large, even in the spring (opposition didn’t come

till August). And, heck, I could see signs of detail in the image on my monitor. Not just the polar cap, but

those always elusive dark markings, the supposed BLUE-GREEN VEGETATION of my boyhood!

|

| Small but sharp: Mars with the Konus newtonian. |

My mind wasn't truly blown, however, till I ran the night’s

.avi movie files through Registax. I

was somewhat familiar with the program already from experimenting with it with

some of my camcorder images, but I didn't expect anything like what I got. What

I got when I finished fooling with the program’s “wavelet sliders” (sharpening filters)

was the best planetary images of my life. And not just that. The detail was

indeed in excess of what Pic du Midi and other professional outfits had done a

decade before. See the video below to get an idea of the difference Registax

made.

So it went, night after night after night. As the planet

rotated, more and more mysterious features came into view and went on the hard

drive (of the desktop computer I dragged into the backyard). Syrtis Major, Solis Lacus, Mons Olympus. I toured all those fabled

sites, and almost felt as if I were on the surface with the crew of Angry Red Planet’s Rocketship MR-1.

Then August was past and Mars was dwindling back to its

normal pink b-b aspect. Was I sorry to see it go? Dang right. However, I must

admit the opposition almost exhausted me. Night after

night with one target, it was the most sustained planetary campaign of my

amateur career, with even my most enthusiastic lunar tears being a distant

second.

Will I return to Mars? I haven't, not with a camera, though

I have visited the other planets with my webcams, which have slowly evolved

into more sophisticated planetary cameras like the ZWO ASI120MC I use now.

However, Mars is growing again from is puny 14” diameter of recent oppositions

to an impressive 24” in 2018, just a smidge smaller than in 2003. You can bet I’ll

have boots on that red, red ground when that happens, muchachos.

Next Time: The Return of the King...

Sunday, February 01, 2015

More DSLR Adventures...

This was originally supposed to have been a “My Favorite Fuzzies” installment,

muchachos; specifically one about everybody’s favorite nebula, M42. But I’ve

decided to hold off on that. One of the goals I’ve set for myself astronomy-wise

is to finally get an outstanding

image of the Great Orion Nebula. Oh, I’ve gotten some OK ones over the years,

but not one I consider “perfect,” even by my modest standards. So what then?

How about more on Unk’s efforts to shoot the sky with Canon DSLRs?

Before we get to that, though, let me tell you my

asteroid story. Last Monday afternoon found Unk scurrying around to set up Big

Bertha, his C11, on her new CGEM mount.

Our quarry for the evening was to be 2004 BL86, an asteroid that was to fly by the earth at a (sorta)

close distance. It was supposed to be close to magnitude 9, and would sail

through a pretty region of the heavens, the area of Cancer’s M44, the Beehive Cluster.

I was all het up to see the flying mountain, and didn't

think there was any way me and Bertha could miss. I had the IDs of several

stars the asteroid would pass close to over the course of a couple of hours on

Monday night. I’d send Bertha to one of these (SAO) stars, we’d wait, and when

the asteroid passed it would be “GOT HIM!”

Monday is my teaching day at the university. I’d be home by

8 o’clock, though, and Cancer wouldn’t be high enough to fool with till 9.

Still, I wouldn’t want to be lugging Bertha out into the yard and setting her

up after dark. I got the CGEM assembled and the C11's OTA on it before I left for the

University of South Alabama at 3 p.m. Monday afternoon.

Arriving back home after spending hours stuffing young minds

with astronomical knowledge, I had to admit I was a tired. But with no

setup required, I wasn’t too worried about that. Got the mount goto aligned, and testing

showed Big B. was putting anything I wanted from one side of the sky to the

other in the center of a 27mm Panoptic eyepiece. That silly little asteroid? I

figgered “no sweat.” Uh-huh...

You know what they say about those doggone best-laid plans, doncha?

With the list of my SAO stars in hand, I punched the first one into the hand

control. Sucka wouldn’t take it. Tried again. Same-same. Tried the 9:30 p.m. star.

Nope. The 10 o’clock one. No way. At first I wondered if my HC was inflicted

with an old Celestron bug that made entering SAO stars fail. Nope, a check of

the version showed that the firmware load that came with the HC was later than

the afflicted build. What the hell…was something broke? Then a light went on.

The Celestron HC has a catalog of SAO stars. But not all 258,000 SAO stars. It only goes down

to about magnitude 7. Hmmm… I ran

inside, fired up SkyTools 3, checked

the magnitudes of my waypoint stars in the program’s Interactive Atlas, and

determined that—shoot—all were dimmer than 8 and would not be in the database of the NexStar hand controller.

That was just OK. I was weary, but I reckoned I could scare

up a serial cable, hook the Toshiba laptop to the mount, and send Bertha to my

stars with SkyTools. As I was

thinking about that, I happened to glance up and to the east and realized my

target area was in the boughs of a pine tree and would be for some time to come.

I shut B. down, headed inside, and had a couple of drinks.

What Unk shoulda done instead of nearly having a melt-down like an emotionally disturbed two-year-old? Sent the scope to the RA and Dec of one of those target stars. Wouldn't have been hard via the NexStar HC's ability to enter "user objects," objects not in the controller's catalogs, something I've done all the time for new comets. But that didn't even cross my mind (such as it is). In my defense, a day with the undergraduates will tire you right out. Those "couple" of drinks <ahem> put everything right, though.

|

| Backyard Comet |

Ah, well. Such are the reefs and shoals of amateur astronomy, as

your Uncle well knows. In other words, “You can’t win ‘em all,” “There Ain’t No

Justice,” and the kind attentions of Mssrs. Murphy and Finagle are always part

of our game. Luckily, my modest successes are frequent enough that I manage to

carry on in spite of all my foul-ups.

“Carrying on” meant your Uncle was still bound and

determined to get a convincing image of Comet Lovejoy's beautiful but elusive tail. I’d captured it (barely) with the Canon 60D and the Patriot refractor from the backyard, but you really had to hold your

mouth just right to see much of it. With the comet past its peak and fleeing

the inner Solar System, I knew I had to get a move on if I were to succeed.

I sure didn’t want to be caught out like I was in the days

of Hale-Bopp. Back then, I was just barely getting back into astrophotography

after a long hiatus. Before the Boppster left, I was able to assemble some

pretty good (film) imaging gear, but by the time I figured out how to use everything

again, the comet was on its way out. I never got the shot I longed for of Bopp's

beautiful blue ion tail.

Saturday seemed to be D-Day for Lovejoy. There'd be a Moon

in the sky, a 4.5 day old crescent, but it would be toward the west. With the

comet near zenith in Aries, I hoped there wouldn't be too much interference. What

would come after Saturday was more Moon and probably more clouds. I rang up my

astrophotography buddy, Max, and it turned out he had the same thing in mind that I did, one last comet campaign from the Possum Swamp Astronomical Society

Dark site.

I was tormented all the way out to the private airstrip we

use for our observing by the suspicion that I’d forgotten something. One time I

nearly pulled over to see if I had left the laptop at home, though I really knew

I hadn't. I was at sixes and sevens, it seemed. What was going on? Your

normally optimistic and ebullient Uncle had been in a subdued mood for days and

days. Why? In part, that was simply what winter does to me. I am a spring –

summer kinda guy, and my head probably won't be back on straight till the

flowers are blooming and bees are buzzing again.

When I arrived at our dark site, I was all by myself at

first. That didn't bother me. While my imaginary (perhaps) friends—Mothman, the

Skunk Ape, and the Little Grey Dudes from Zeta Reticuli II—often keep me

company on the observing field when I am alone, I knew they wouldn’t bother me tonight. Even if Max didn't show. I didn't have that creepy feeling that presages their

visits. Instead, I had the blahs, which are a click up from the

blues, if not quite to the level of Holly Golightly’s Mean Reds. When I am like

that, the fantastical baddies have no power over me.

As I began unloading, it was clear I needn't have been

paranoid about leaving some important piece of gear at home. I’d been

reasonably careful with the packing, but the mainly there just wasn’t that much

stuff. At least as compared to, say, a Mallincam run with the C11. There was

the evening's telescope in her case, once again the little 66mm WO. She'd have enough field

to take in plenty of tail, should I be able

to capture much tail. There was also the VX mount and tripod. The Toshiba

laptop. The Gadget bag with my Canon DSLR bodies in it. Couple of accessory

boxes. Three jump start batteries. And that was it. That may sound like a heap

of gear to you Dobbie fans, but for Uncle Rod that is “traveling light.”

Alright. How was the sky looking? Good, very good. Entirely

cloudless. There was occasionally a light breeze, and the air felt dry. Yeah,

the crescent Moon was burning surprisingly bright in the gloaming, but I knew it

would be like that going in. I’d rather have the Moon than the cotton-picking

clouds that have deviled me all fall and most of the winter thus far.

When the scope was assembled, next step was checking

balance. I would be going unguided, and even at the short focal ratio of the 66mm

scope, just a smidge less than 400mm, good balance would be important. I

attached the Canon 60D to an SCT prime focus adapter (as noted in last week’s

blog, the 66mm SD scopes of yore all had SCT rear ports) and adjusted the

counterweight on the declination shaft till the mount was east heavy by a small

amount. That ensures the gears are always engaged and improves tracking on

almost any mount.

|

| Alternate take... |

Balancing done, I removed the camera and re-installed the

2-inch SCT style diagonal. Yeah, I could do the goto and polar alignment with

the camera, but I find it quicker just to use my old Meade 12mm MA crosshair

eyepiece. Did a 2+4 goto alignment, and dialed in polar alignment using Cetus’ Diphda

as my AllStar Polar Alignment star. Since I'd moved the mount a fair distance in

altitude and azimuth to polar align, I redid the 2+4 to ensure bang-on

pointing. Given the wide field of the scope, I could probably have gotten away

with not redoing the goto alignment, but I could, so I did. The closer the mount

put objects to dead center in the field, the quicker I would be able to work.

Hokay. Started Nebulosity

3, plugged the camera’s USB cable into the PC, and focused up. I was still

sitting on my last calibration star, Aldebaran, so I used that to achieve rough

focus. When it was nice and small, the dim field stars began to be visible in

the successive 1-second exposures in Neb’s Frame and Focus mode. When they were

as small as I could get them by eye, I switched to Fine Focus, clicked on

a small field star, and made its Half Flux Radius number as small as I could

get it.

Onto Lovejoy. Just as I had for my previous expeditions to the

visitor, I’d printed out an ephemeris with my favo-right planetarium program, Starry Night Pro Plus 6. I entered the set

of coordinates closest to the current time into the NexStar HC using the “goto

R.A./Dec” utility, pressed “Enter,” and away went the VX mount. When it

stopped, I fired off a 5-second exposure using Neb’s Preview function. There the

hairy star was, well framed and not looking any dimmer than she had a week

previously.

Before I spent an hour or more on the comet, however, I

wanted to know whether the tail was doable or not. I set the ISO of the Canon

to 3200, which might be pushing it a little in the Moonlight, but which might

help with the subtle tail. Set the exposure time to 2-minutes, and mashed

“Preview.” What did I see when the finished picture appeared on the laptop screen? The

stars were nice, round pinpoints. It sure is nice the VX - Patriot combo doesn't

require guiding for 2-minute exposures. The tail? Easily visible, but not

exactly putting my eye out. It was good

enough, though, that I thought I might really get something if I stacked 30

2-minute subs.

I set up the exposure series, hit the “go” button, and Nebulosity and the Canon began doing their

thing. What now? I wandered the field, spending some time watching Max,

who’d arrived as I was setting up the telescope, work with his VX, his wide-field 5-inch Newtonian,

and his Sony Camera. He was getting some nice frames already. Another PSAS

buddy, Gene, had showed up at sunset, and I enjoyed observing this and that with him using his nice visual rig, a 6-inch f/8 Celestron refractor

on an Atlas mount. I’ll tell y’all, if the six-inchers weren't so blamed heavy,

I’d have one.

Mostly, though, I scanned the skies with Miss Dorothy’s

prized Canon roof binoculars. They are “just” 32mm glasses, but they are finely

made, and with a magnification of 8x they don't give up much—if anything—to a

pair of el cheapo 10x50s. I looked at all the obvious binocular stuff,

including M42, which is now getting nice and high in the east early in the

evening, and Gemini’s M35. Mostly, though I looked at Lovejoy.

It was bright in the glasses. No tail, but a prominent nucleus and plenty of coma. My main goal

was to pin down the comet’s position exactly and see if I could detect it naked eye. I’d thought I’d maybe glimpsed the fuzzball from the backyard on

one good night not long before Lovejoy’s peak, but was not totally sure. On

this night? I was pretty sure. There

seemed to be a dim fuzzy in approximately the correct location, but it was not an easy

observation even with the comet riding high and in skies considerably darker

than those of the New Manse’s back-forty.

There was still quite a while to go on the exposures, so I

did a little more binocular gazing and had a peep at M82 in Gene’s

refractor—just doesn't seem possible Ursa Major is back already. As Max waited for his sequence to complete and I waited on mine, we got to talking comets. Sure

would be cool to get a great one soon. The last comet we had that even comes

close to that appellation was weird Comet Holmes (which is undergoing a minor

outburst right now), and hard as it is to believe, that was seven freaking years

ago. We are almost in a comet drought

like the one between Halley and Hyakutake.

Just as I was getting warmed up on the subject of My Favorite Comet of All Time (West), the Toshiba

Laptop played the little fanfare that is Nebulosity’s

way of saying “Sequence is done, Uncle Rod.” Hmm. What now? I could do more

comet frames, but I believed I had enough for a reasonable image. I wanted to

do one more target, though, and the natural seemed to be M31, which was not too

high and not too low.

As I mentioned here, I’ve

been after a good picture of the famous Andromeda Nebula (Galaxy) for a long

time, and I thought the little Patriot would have the field to do a nice job on the huge object. Did a preview shot of the galaxy, and the framing was

good without me having to touch a thing other than change the camera angle (the

Patriot has a rotatable focuser) so the galaxy was a little more horizontal. The

Moon, not too far away, was obviously making the background brighter than it

would normally have been, but watcha gonna do?

Set up for thirty subs of the beast. That would take a while, and it was now a bit on the chilly

side, but I figgered if I were gonna do it, I’d do it right. Once the sequence

was underway, I walked over to the fire-pit near the hangar where

the remains of a fire built by one of the airfield’s owners still burned. I sat in a lawn chair and warmed myself while waiting for M31 to

finish.

Actually, it was not terribly cold. It should have been chillier,

but the humidity had spiked up at mid-evening and so had the temperature. I

knew what that meant: clouds coming. And more than a few were now visible

on the western horizon. There was no doubt, however, that I’d get M31 in the

can before they arrived.

When the galaxy finished, me and my two companions were not

quite ready to call it a night, though we thought the end was in sight. Just

for the heck of it, I slewed over to the Horsehead Nebula and did five

30-second frames. After that, I packed up and pointed the 4Runner for the New

Manse, quitting the site well before midnight.

As is my usual wont, I studiously avoided looking at any of

the images when I got home. They always look horrible at the end of a long

night, and I knew they would appear far better in the morning. Instead, I

surfed the cable TV channels for a little while, warmed myself with the aid of

the sainted Rebel Yell bottle, and, finally toddled off to bed as midnight came

and went.

Next morning I copied all the subs from the laptop to the

desktop in my office over our home network and went to work, starting with the

comet. Only problem I had was that in these fairly long subs, the nucleus was

not a “star.” It was a sizable ball, and it was a little hard to position the

cursor in Nebulosity dead center enough

on it to ensure good stacking. In the end, I did two separate

stacks.

The verdict? I’ve seen far better images of the comet’s tail

on Facebook, but given the Moon’s presence, I’m pleased. The coma is, as in my

backyard pix, a pretty green. More importantly, the comet’s tail and spiky

secondary tail(s) are just as distinct as I’d hoped they would be. Perfect? No,

but I most assuredly did not let this

one get away.

M31 was another winner by my humble standards. Oh, it would

have been better without Luna nearby, but not bad. I hope to do better still,

but I would not be surprised if that has to wait till next year. In a month’s

time, assuming the clouds leave me alone, it’s possible I might tackle it again, but it will be beginning to get low by the

end of any decent exposure sequence, and I am skeptical the weather gods will

cooperate. We’ll see.

Perhaps the biggest surprise of the evening? The Horsehead

Nebula. With only 150-seconds of data (though I did crank up the ISO to 6400),

there was no way this was going to be a pretty picture. However, I did get a

picture and not an entirely horrible one considering. The Horse is there, and

there is even a little detail in the red background nebula, dim IC434.

Which makes a point I’ve been talking up for some time.

Novice imagers who spend their time reading in the Internet astronomy chat-rooms

have the idea that you must have your

DSLR modded (have its built in IR filter removed) to do any deep sky imaging. Clearly not true. Modding a camera helps,

muchachos, especially with dim red nebulae, but you can still get ‘em with your

stock DSLR. It’s a little harder and takes a little longer but you can do it.

If your fumbling and bumbling Uncle can image the freaking Horsehead with his

unmodified Canon 60D with less than 5-minutes of exposure, the sky is, quite

literally, the limit.

Next Time: Big

Time…