Sunday, February 01, 2026

Issue 624: The Messier Project Night 5: Orion and Taurus

Taurus

M1, the Crab Nebula

Messier 1, Ol’ Crabby, as I called M1 as a boy, a supernova remnant, was discovered by English astronomer John Bevis in 1731. Like more than a few M-objects, it was subsequently “lost,” only to be rediscovered by Charles Messier in 1758. Where does the "Crab" business come from? In the 1840s, Lord Rosse thought the nebula resembled a crab in his big, Dob-like reflector. Why he did, I do not know. It doesn’t look anything like a crustacean to my eyes, or even in Rosse’s original drawing. As most of you know, the Nebula is the remnant of the “guest star” of 1054 recorded by the Chinese. A famous pulsar hides within its folds.

So, how does it look? If you’re a wet-behind-the-ears

12-year-old observer with a 4-inch Newtonian, it doesn’t look like much

from a suburban backyard. This was one of the first deep sky objects little

Rod located, and suffice-to-say, he was not impressed. I likely passed over it

a bunch of times, since, based on the observatory astrophotos in library books, I thought it

would be mucho brighter. What it was was a dim oval of light in the

field of my ½-inch Ramsden eyepiece. I was disappointed. M1’s visual

magnitude figure, 8.8 made is sound reasonably easy. Alas, it’s 8.0’ across, fairly

large, so that light is spread out.

As with many nebulae, a light pollution reduction filter is key to seeing more detail. In my 12-inch, Old Betsy, an OIII filter finally allowed me to finally observe the filaments that crisscross M1. While the filter enhances these streamers of gas, it darkens the main body of the nebula. With no filter, in Old Betsy and my current “big” scope, Zelda, a 10-inch, the gas filaments disappear, but the nebula's zed or lightning bolt shape becomes clear. The other night with the 6-inch Dob (who has stubbornly not yet told me her name), we were back to the “dim oval” stage.

Suzie, the 50mm ZWO S50 smartscope, had zero trouble with Old

Crabby. 45-minutes of exposure in equatorial mode revealed many of the details of the astrophotos in my 1960s astronomy books. Quite amazing,

if you ask me. The color is the only thing that has me scratching my head.

I’d expected a little green from OIII emission, but that’s not what Suzie’s

dual-band filter delivered. I will not quibble with Suze; she did a terrific

job for a wee little girl.

M45

The seven sisters, the Pleiades, were covered in my blog

article on the 2025 Deep South Star Gaze here.

Orion

M42 and M43

The Great Nebula in Orion is the deep sky object to end all deep sky objects—in the

Northern Hemisphere, anyway. I’ve talked about my first looks at M42 as a kid before, notably here, so there

is no reason to further gild that lily. It is terrific in any scope or

even in smallish binoculars. If M1 tore me down, M42 built me back up

and inspired a lifetime of deep sky observing.

I simply never tire of Messier 42. After 60 years of

admiring it, I always find something new. After I got old Betsy and acquired

some LPR filters in the early 1990s, I saw more than ever. Notably, intricate detail

in M43 and the space between it and the main nebula. Though Old Betsy is long

gone, I find the view in the 10-inch nearly equal to what I saw in the 12-inch.

And I see more today. My eyes aren’t as good, no, but I can observe M42

on any clear night in a suburban sky far superior to the city one I had to deal

with in Bet’s heyday.

John Mallas does a fine job of summing up the glory of M42, “Here is one of the most remarkable areas

in the heavens. So many details are visible in even a small telescope that it

is difficult to make a realistic drawing.” As is often the case, John’s drawing

of the Great Nebula is more of impressionistic than realistic. Over the years,

some have criticized his style, but a long time ago I discovered that if you

view the drawings in the book under a red light, they look remarkably like what

you see in the eyepiece of a small telescope. The Kreimer image wouldn't win any prizes today, but back in the long-ago it was a masterpiece, a revelation.

The very first object I imaged with Suzie two years ago was

M42. That was the place to start, a nice bright object while I was learning to

use the smartscope. My results firmly clued me in that there damn sure was

something to this smartscope business.

M78

The other Messier in Orion is the (seemingly) small reflection nebula M78. It’s yet another M not discovered by the Man himself, but by his eagle-eyed friend Pierre Mechain, who stumbled across a patch of nebulosity in 1780. He told Messier about it, and Chuck immediately added it to his catalog as another comet imposter. It is similar in size and brightness to M1, being at magnitude 8.0 and 8.0’ across, but to me, anyway, it seems easier to see in a small instrument.

M78 is just one small part of an area littered with reflection and emission nebulae. It is merely the brightest member of an interconnected group that includes NGC 2064, NGC 2067, and NGC 2071. All these objects are part of the so-called “Orion B” molecular cloud complex, which is about 1,350 light-years from the third stone from the Sun.I must have observed M78 as a boy; the brightest portion of

the complex, NGC 2068, is not difficult in a small telescope. I was, no doubt,

not overly impressed, though. In a 4-inch from the suburbs, M78 is nothing more

than a slightly oval nebula surrounding a pair of stars. When did I begin to

see more here? Not till quite a while later when I had darker skies and bigger

telescopes. And nebula filters. “Nebula filters?! This is a reflection

nebula, not an emission nebula, Unk! A filter won’t help.” Not quite, Skeeter.

There is emission nebulosity here, too, and when I glommed onto that fact, I began

to see even more in the area.

John Mallas observation of M78 lies somewhere between what I saw as a kid and what I can see of the nebula now. He describes it as comet shaped, which had me scratching my head till I realized he was seeing the faint finger of nebulosity that extends to the east, quite an accomplishment with a 4-inch achromat.

By the time I got around to turning the S50 on M78, I was aware

how powerful the little telescope is, so I shouldn’t have been surprised at

what she brought back—but I was. Swathes of gas and dust crowd the frame.

The Bottom Line:

16 Down, 94 to go...

And that is going to be a wrap for this one, muchachos. I

am off to visit the lovely Miss Dorothy. I missed posting the January AstroBlog,

barely, the first time the blog has missed a month in a long time. I intend to

make it up with a “bumper” February article, an extra one, if the sky and

events cooperate. Excelsior!

Wednesday, December 24, 2025

Issue 623: The Messier Project 4 and a Chaos Manor South Merry Christmas

Christmas Eve has once again come to Chaos Manor South. It snuck up on your aged correspondent. Wasn’t it just yesterday that Unk celebrated his summertime birthday with a POTA activation and margaritas at El Giro’s? Enough of that. It is what it is; Christmastime is here! We’ll get to the Yuletide doings ‘round the manse in due course, but first let’s talk about the next bunch of Messiers…

Perseus and Auriga

It wasn’t just Christmas that snuck up on your Old Uncle. I belatedly realized the western reaches of Perseus the Hero are getting awful close to the Meridian by mid-evening, and that’s not a good place for picture-taking. With no time to waste, Unk set up Miss Suzie, the ZWO smartscope, in the back forty on a clear but damp late fall evening and got to work.

Messier 76

First up of Perseus’ two Ms was the Little Dumbbell

Nebula (aka, “Barbell” and “Cork”), NGC 650, a well-known if not oft-observed

planetary nebula. Once again, we have an object not discovered by Chuck Messier

himself, but by prolific observer Pierre Méchain

(in 1780). M76 is a magnitude 10.1 planetary nebula, the corpse of a

dead star, that measures 3’07” x 2’18”. And there you have the two things

that account for M76’s relative lack of popularity with observers: It is

small and sounds as if it will be faint.

I had intended to observe M76 visually with Zelda, the 10-inch Dob,

but wimped out. What I shoulda done was haul Miss Zelda outside in late

afternoon. Alas, I got distracted by other things, and it was dark before I

knew it. I wasn’t about to lug her down even the few steps of the deck in

anything but broad daylight, so I settled for little Tanya,

my 4.5-inch f/5 rescue-scope Newtonian.

I suppose getting under dark skies with Z for a few nights

at the Deep South Star Gaze got me back in the red-dot finder groove, because I

had no problem getting the Little Dumbbell in the field of a 10mm Plössl (one

of the two the humble eyepieces Celestron included with Miss T.). I wouldn’t

say the nebula was bright without a filter, but it was doable. While

some will tell you M76 is a tough Messier, it’s not. The nebula’s small size

keeps its surface brightness relatively high, and adding a light pollution

reduction (LPR) filter makes observing it like shooting fish in the proverbial

barrel. I routinely viewed this planetary from the suburbs with my old and

long-gone ETX-60 (with a filter).

OK, so what was M76 like in The Tanya? Unfiltered at

57x with the Celestron Plössl, the nebula was a small rectangle of haze just at

the limit of visibility. While dim, it was obvious the second I looked into the

eyepiece. It still didn’t put my eye out when I replaced the el-cheapo ocular

with a decent 6mm Orion Expanse (95x). I added an OIII filter, and, yeah, better

(the OIII is the filter for most planetary nebulae). I even imagined I

at least detected the streamers of gas that wrap around the central bar of M76.

I plan to move on from John Mallas and Scotty Houston

to other observers as this series progresses but seeing as how I was observing

with a 4-inch just like John M. (if one with a far less impressive pedigree

than his big Unitron), I thought it would be appropriate to turn to The

Messier Album once again.

Suzie had zero trouble imaging the planetary, but I wasn’t satisfied

with our results. While Astrospheric and Scope Nights had predicted

clear weather for the entire night, Siri disagreed, intoning, “Clouds at

mid-evening!” I thought my favorite AI girl was skipping a few gear teeth,

but it turned out she was correct, as she usually is. I had less than 20

minutes on the nebula when a message popped up on the ZWO app: “Image discarded,

not enough stars,” Rut-roh, I popped outside and looked up: Clouds,

thick clouds, and plenty of ‘em. We got another chance the following night and

accumulated 45 minutes of exposure.

Let’s face it, M76 is small for a 50mm f/5

smartscope. Nevertheless, Suze turned in a credible effort. After zooming-in

via cropping the image (zooming is more practical using Suzie’s EQ mode, since

you don’t have to worry as much about egg-shaped stars as you do in alt-az),

the two streamers of gas are prominent, as is the nebula’s green OIII color,

and even some tinges of red. Good show, girl!

Messier 34

The other Perseus M, open cluster M34 (NGC 1039), is

probably a Giovanni Batista Hodierna find; he

appears to have observed it from Sicily in 1654. If he did, nobody outside

Sicily heard about it. What is known for sure is Charles Messier—who doesn’t

seem to have known about Hodierna’s work—saw it, resolved it, and cataloged it

a decade later: “A cluster of small stars, a little below the parallel γ

Andromedae; in an ordinary telescope of three feet [focal length] the stars can

be distinguished.” M34 is bright at magnitude

5.8, but also spread-out at a size of 35.0’.

With a little extra aperture, M34 was visible in a 20mm Expanse (Synta-made) widefield ocular at 37x. Visible, yeah, but not what you'd call "rich." Nevertheless, I declared it a win on a night like this one. The brighter cluster stars were there, but dimmer members and the scads of background suns were absent. That lack of background stars actually made M34 stand out better. "Spiral cluster"? Maybe it's just me, but I scratch my head over that one. What I see is a medium-rich group dominated by star chains.

John Mallas calls this “A very fine cluster,” but opines

that this is an object for smaller apertures due to its large size. That is

still somewhat true, but we now have richest field telescopes and

widefield and ultra-widefield eyepieces. Today, this one is a standout in

larger-than-4-inch scopes, too.

Suze did a fine job on this galactic cluster, but her image

highlights the cluster’s “problem” in images and with larger aperture

instruments under dark skies: It tends to melt into the rich background

starfield.

Onward to Auriga we go. The three famous Auriga open

clusters are a sentimental favorite of mine. I could occasionally coax my Old

Man, W4SLJ, out of the house for a look through my Palomar Junior on

long-lost 1960s nights. While he was mainly interested in seeing the Moon and

planets, he did like M42, and, maybe even more, the Charioteer’s clusters. He

referred to them as “The Big Three,” and always requested I point my

little scope at them on winter nights. How I wish I could have shown SLJ these

three wondrous star nests from the dark skies of the Deep South Star Gaze with

my 10-inch telescope… Anyhow, we begin with the westernmost group.

Messier 38

In John Mallas’ beautiful—if small-aperture—Unitron, his

impression was “[S]quare-shaped with a clump of stars at each corner.” I can

see that, yeah, the central region, the “body” of the starfish or spider, is

squarish. I don’t see clumps of stars, though, I see chains. Neither of

us is wrong. Looking at galactic clusters is like looking at clouds; you see

what those shapes suggest to your mind. Overall, Mallas was

impressed, “For small apertures, this is a beautiful cluster in a rich field.”

With that, I agree, but the same goes with larger apertures with appropriate

eyepieces.

In the ZWO smartscope, M38 looked much as it had to my eye

in Louisiana. OK, OK, I’ll admit Suze saw more background field

stars from the backyard than I did with a 10-inch from a dark site. There was a

bonus, too, one I overlooked with the Dobsonian. At the edge of the frame is

another open cluster, little (5.0’) magnitude 8.2 NGC 1907. Not only did

I miss it in the eyepiece at Feliciana, I didn’t notice it in Suzie’s shot

until the exposure was done. If I had, I’d have reframed the picture to show it

better—or at least have turned off the ZWO’s watermark.

Messier 36

M36, NGC 1960, was first seen by Hodierna in 1654. He

had no idea what it was, being unable to resolve its stars with his small

instrument. It was merely another intriguing “nebulous patch,” which could be

anything. Following Hodierna, it was

rediscovered and lost again time or two before being spotted by Messier in 1764

with his 3-foot telescope. Charles was the first observer to resolve the

cluster. M36 is both smaller (10.0’) and brighter (magnitude 6.5) than

neighboring M38.

This M-object is often called “The Pinwheel Cluster.”

I’m not sure that’s what I saw with Zelda on those Louisiana nights, though.

Oh, it was beautiful, but my impression was mostly of a rich splash of stars

with a medium-dense center. It’s tight but doesn’t begin to look like a loose globular.

Maybe 10-inches was too much aperture to give a pinwheel impression, resolving

too many dim stars. Anyhoo, I liked it best in the 13mm Ethos (115x).

Mallas, thanks to his smaller aperture, had an easier time

seeing an overall shape. However, he doesn’t seem to have seen a pinwheel

either, “Outward streamers of faint stars gave a crab-like appearance.” He does

note the same thing I did, the lovely color contrast among the cluster’s suns.

Not too much to say about the smartscope’s take on this one.

M36 is without doubt the weakest of the three Auriga clusters. It looks good in

Suzie’s shot, but pales alongside M37, of course.

Messier 37

For Unk, there is no contest; M37 is the best, the richest,

the most beautiful. In the 10-inch, it was a mind blower, looking more like

a loose globular than a galactic. What I saw was a triangular core about 5.0’ in

size surrounded by an outer halo of stars bright and dim, all looking tiny and

marvelous. The cluster’s renowned red central star was more than obvious. My

most memorable view of M37, however, was with my old C8, Celeste, one dark

winter’s eve’ sixteen years ago at the Chiefland

Astronomy Village:

This gorgeous open cluster in Auriga was just

indescribable in the 13 Ethos. At times it looked almost like the south’s great

globular cluster, Omega Centauri. At other times, it assumed weird shape and

substance. One time I found myself seeing the central triangular area of the

cluster as the head of a raging bull, M37’s red central star forming its

baleful eye: the whole thing a miniature Taurus.

John’s opinion of M37 in The Messer Album mirrors my own:

“This is one of the finest open clusters in the heavens.” Maybe I’d change that

to “the finest.” This group

is often called the “Salt and Pepper Cluster,” but that doesn’t seem adequate.

Maybe the old “diamond dust on black velvet” cliché is the best

description of this wonder.

There’s nothing to complain about in Suzie’s picture of this

great cluster. It’s just beautiful. It’s not a criticism to say it looks

less like a loose globular than just a rich galactic cluster; that’s the

difference between eyepiece impressions and looking at an image. When you study

a photo of M37, it is obvious the group doesn’t come close in richness to even

a loose glob like NGC 5053. I am very pleased with little Suzie’s image,

though.

Cleanup on Aisle Cassiopeia!

I should have stopped by Messier 103 when I observed M52 at

Deep South. Somehow I forgot about it, though, so I made my way over to this

spectacular cluster once Zelda and I returned home.

Messier 103

Yeah, I sure wish I’d turned the 10-inch to M103 during the star

party, but I didn’t, so I'd have to see what a small reflector would do with the

group from home. When Miss Dorothy and I moved out here a decade ago, my

backyard skies were often impressive. Now, they have gone from the “suburban-country

transition zone” to the “suburban” category.

I viewed M103 on the same night as M34, and it also got the 6-inch treatment. Despite haze that was rapidly thickening to fog, the cluster was immediately visible when we were on the field. However, the lovely arrowhead of stars that defines it was, well, small, real small. Tanya would have had a hard time here. In a 9mm Expanse (83x), the 6er gave a decent view. The Arrowhead even gave up a few of its dimmer suns.

John really dug M103. How could he not? “A grand

view! The stars form an arrowhead which is also seen in photographs. A 10x40

finder resolved the cluster, but the 4-inch showed the fainter stars, many of

them colored.” Indeed, one of the most beautiful aspects of this group is the

contrast between the cluster’s blue-white stars and one bright, orange luminary.

Open clusters are duck soup for the S50 smartscope from the

suburbs, and Suzie’s image is a nice one. The only way I might improve upon it is

to give M103 a longer exposure than the 10 minutes I allotted to it. The

picture’s not bad, but there is a little more noise than I’d like.

Christmas Eve 2025 at Chaos Manor South

It is again time for ho-ho-ho and mistletoe and presents to pretty girls...Despite the predictions of the weather goobers, it was dead clear. Why, it was a blue-eyed Christmas miracle! I wasn't up for taking even little Tanya out by this point in the game, so I went back inside and grabbed my trusty Burgess Optical 15x70 binoculars. Oh, how the sword shone! As it had shone on so many Christmas Eves going back to the 1960s. I stood out in the yard and drank in the beauty the sword for quite some time. Almost sated and a little weary, I made my way back

inside, and, finding myself somewhat refreshed, pulled out the Rebel Yell bottle and got Tom, who was

now also wide awake, set up with a new video and some catnip.

No, it didn't feel much like Christmas, but I saw the Christmas ornament of all Christmas ornaments! Now, I’m being called upon to

break out more catnip and put on Midway one more time. So, it goes. HAPPY

HOLIDAYS one and all. See ya next year.

The Bottom Line:

12 down, 98 to go…

Thursday, November 27, 2025

Issue 622: The Messier Project Night 3 at the Deep South Star Gaze, “The Water Constellations”

Thomas Wolfe said, among many other things, “You can’t go home again.” Is that true? Mostly, muchachos, but not always and not completely. If you’re a long-time reader of the Little Old Blog from Possum Swamp, you know our local star party, originally the Deep South Regional Star Gaze, and now the Deep South Star Gaze, was an every-year tradition with me and Miss Dorothy for over two decades. But then much changed. We retired, the pandemic came, and the star party moved to a new location.

We visited its new venue, a private religious camp, for the 2023 edition, but above and beyond clouds causing a good, old-fashioned skunking on all three nights (which can happen anywhere, anytime), we were not happy with the facility and the food. Most of all, it just didn’t have that “Deep South feel” and Dorothy and I reluctantly decided we wouldn’t be back.

Then, a few months ago, we got word from DSSG’s longtime director, Barry Simon, that our favorite star party would be moving back to its previous home, The Feliciana Retreat Center (FRC) in Norwood, Louisiana, a place we’d always liked, for the 2025 edition. Dorothy and I didn’t have to do any thinking; we sent in our registration and began looking forward to going home again.

As the big day approached for us, November 20 (we’d attend Thursday - Sunday of the event), I began ruminating on the equipment I’d haul to the backwoods of Louisiana. Certainly, I’d take Zelda the 10-inch Dob, who is now my big gun, but what else? I’ve yet to get Suzie, my ZWO S50 smartscope under dark skies. And, hey, why not take the Unistellar 4-inch smartscope, too? I could do visual one night and devote the other two to the smarties. But then everything changed.

|

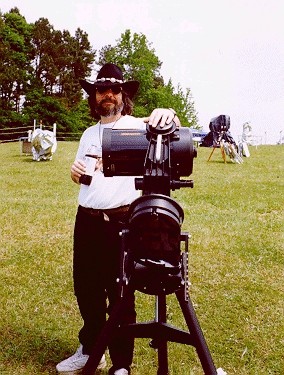

| Unpacking at the Lodge. |

There was never any thought of us not going, though; even if all we could do was visit with our friends we would be there. Still, what I go to a star party for is deep sky wonders, and I was feeling disappointed. Then, a few days before the DSSG kickoff, the forecasts improved—a little. It appeared we’d get some observing in Thursday, little to none Friday, and maybe a lot Saturday. Whew!

If I was gonna see anything, I’d need an observing list. That wasn’t difficult to compose. My current obsession, as you know, is (again) the Messiers. I don’t have a good southern horizon at Chaos Manor South, so I would concentrate on the southern “water” constellations, on the Ms in Pisces, Aquarius, Cetus, Capricornus, etc.

With DSSG week almost here, it was time to round up all the old outdoor gear we’d used at so many star parties. First up, though, was a trip to Academy Sporting Goods for a replacement for the ginormous Plano tacklebox I used as an equipment case for years and years. It's still in perfect shape but is now too heavy and awkward for me. I purchased a (much) smaller one as its replacement. We also picked up a sleeping bag for Miss Dorothy, since hers had gone missing.

We’d need bags since we weren't sure Feliciana would provide bedding, and it’s easier to bring a sleeping bag than fool with sheets, blankets, etc. Naturally, the Wednesday afternoon before Deep South, when it was time to load the 4Runner, Miss Van Pelt, my bag was also MIA. Luckily, it (and Dorothy’s old sleeping bag) turned up just before Unk headed back to Academy for another one.

I also found the little black cat heater I used on chilly nights on the field years ago. I put it back away, since the weathermen were unanimous in saying we wouldn’t need it. Highs would be in the 80s and lows in the 60s except for Saturday, which might get into the 50s. The Coleman chairs were accounted for and so was the camp/observing table. While our picnic canopy, our EZ-Up, was looking a little time-worn, I judged it good enough for one more star party. I’d sprayed it with 3M waterproofing in 2023, and we’d never even set it up on the field that year. Now, I just had to get everything into the 4Runner...

|

| Back on the old field 8 years later! |

The trip itself was nothing. It’s just under three hours on I-10, I-12, I-55, and a short stretch on Louisiana back roads. It was entirely uneventful save for me not recognizing any of the scenery or landmarks along the way as we neared Norwood. I guess eight years’ absence will do that for you. Thanks to my trusty GPS, we found the FRC entrance without incident and were soon rolling onto the grounds.

So, out on the field, what was the deal? Partly cloudy. Warm, very warm. A feel of possible bad weather in the air. You know what the whole thing reminded me of? Miss Dorothy’s first star party in 1994. While that was earlier in the year and at the event’s original home, Percy Quin State Park in Mississippi, the feel was eerily the same: Heat and humidity and maybe not much observing. The weather goobers were now warning of possible severe weather Friday, but it looked like the really bad stuff might bypass Norwood.

Field set up was easy enough, since there wasn’t much to set up. The main task was getting the EZ-Up erected, but with Dorothy’s help, and the help of a fellow ham (I counted at least five radio amateurs in attendance), we got the thing up before your old Uncle was quite drenched in sweat. It is nothing to set up a manual 10-inch Dobsonian (other than me struggling with the weight of Zelda’s steel tube). No computers, no cables, no batteries. With the chairs, table, and ice chest out of the truck, we motored up to the lodge to see what was what.

My impressions of the FRC lodge nearly a decade down the road? The dining area looked as nice as ever, very nice, that is. Our small motel-type room? I didn’t notice many improvements/changes, but it was obvious the rooms were better maintained than they had been the last several years Deep South was at FRC (which is now billing itself as the “Feleciana Retreat and Conference Center). They had replaced the mattresses with better ones, and bedding was furnished, making our sleeping bags superfluous. All that remained was to hang out on the field with the old friends we’ve observed with for three decades and wait for supper at 4pm. How would that be?

The answer was “better, much better.” The young couple doing the cooking and serving did a fine job, and Thursday’s BBQ chicken was some of the best star party food I have eaten in a while. One of the things that impelled Deep South to leave Feliciana in the first place was a decline in the quality and quantity of food. I deemed that fixed. Supper done, it was time to get a move on. With the temperature in the 80s, it didn’t feel like late November, but it was, and darkness would come not long after 6pm.

The way the skies looked Thursday afternoon, I’d feared the night would be a complete washout (maybe literally), but as astronomical twilight came, the clouds scudded off, or at least a giant sucker hole grew until it encompassed the entire sky, giving us a couple of hours of cosmic voyaging. I’m afraid I spent most of that time fumbling and bumbling with the telescope, though.

Your silly old Uncle was way out of practice using a dob under a dark sky. I had an awful hard time getting used to using the Rigel Quick Finder zero-power finder again. That wasn’t all. It seemed I had forgotten exactly how to work AstroHopper, the iPhone app that guided Zelda to her targets. I eventually got mostly in the groove with all that jazz and knocked a few list objects out.

Note that on all three evenings I observed quite a few objects in addition to the list Messiers. But this is about the Messier Project and those are the objects Unk is gonna (mostly) tell you about…

Images were shot with Suzie from Chaos Manor South Shortly after DSSG.

M2 (Aquarius)

|

| Did not like the way the sky looked Thursday afternoon... |

Despite swimming in and out of the haze that was beginning to cover the southern sky, M2 was well-resolved by Zelda, looking like a sparkling blue sapphire in the 13mm Ethos eyepiece at 96x. I hadn’t seen this glob, a favorite of mine in my old 12-inch telescope, looking this good in a long time. That haze no doubt reduced the cluster’s brightness, but it was still bright and prominent and well-resolved.

M2 is yet another “Messier object” not discovered by Charles Messier. Credit for that goes to. Jean Dominique Maraldi, who was out observing a comet with his buddy, Jaques Cassini, one nice French night in 1746. Charles is credited with the cluster’s rediscovery in 1760. You won’t be surprised to hear his tiny scope didn’t resolve any stars and is listed as a “nebula without stars.” In fact, nobody realized it was a star cluster till William and Caroline Herschel had a look at it some years later.

Turning once again to my favorite Messier book, The Messier Album, John Mallas is enthusiastic about M2: “A beautiful object.” I can’t compare his observation to mine, since my instrument, Zelda, was so much larger than his 4-inch Unitron. He remarks his scope was only able to resolve “[A] few bright members across the nebulous image.” While Evered Kreimer’s photo wouldn’t be anything to write home about today, it was groundbreaking for the time.

|

| It's hard to get a bad image of M2! |

M72 (Aquarius)

The other Messier globular in Aquarius, M72, is that horse of a different color (the one you’ve heard tell about), being both considerably dimmer (magnitude 9.2) and smaller (6.6’) than monster M2. Discovered by Pierre Mechain, Messier observed the cluster the following year, 1781.

Messier 72 is a small, subdued globular cluster and looked it on this evening. That doesn’t mean it was difficult to see, even in worsening conditions; it was obvious as a small fuzzball in the 27mm Panoptic when I put my eye to the eyepiece. The 8mm Ethos delivered a little resolution at 156x, but it was still more “grainy” than “resolved. The core of this Type IX cluster is quite loose but still fairly bright.

This was not an easy object for John M’s 4-inch achromat. In his scope it was “A very small and nebulous patch of light” He was able to tell detect M72’s loose structure, however.

It wasn't so much that this was a dimmer object, but that conditions were not right for imaging. Miss S50 and I went after M72 anyway, and at least we got a little "cosmic postcard, " a memory of a night under the stars, for our efforts

Sadly, that was it for list-objects on Thursday evening. The southern area of the sky was out of action by 7pm. I spent the remainder of the night looking at some pretty stuff (the Veil was decent, and M15 was a mindblower at high power) before retiring to the lodge room just before 9 for YouTube videos and sarsaparillas.

Then came Friday morning. How would breakfast be? Good. Very good and lots of it. The star of the show was the biscuits and sausage gravy. There was more—eggs, grits, sausage--but that was just the supporting cast for Unk. Excellent.

|

| Suzie's M52. |

Well, until I tried it. Simulation Curriculum, the makers, didn’t do a good job porting it from the iPad to the Apple Silicon Macs. Zooming is broken. Oh, you can zoom, but you have to use buttons. For me, zooming with the mouse/trackpad is erratic at best. Luckily, 6 is still on the Mac and that is what I will use. Maybe they’ll fix 7, but after this long, I doubt it.

Following

a great supper of Thanksgiving ham, dressing, and all the fixings, Friday

night started out promising, but clouds began rolling in not long after dark. The

southern constellations were soon gone, but the north-northeast was

clear for a while, and that’s where me and Zelda went. Starting with a look at

a nice open cluster...

M52 (Cassiopeia)

Finally a Messier Object discovered by Messier! He spotted this galactic cluster floating along the Cassiopeia Milky Way in 1774. At Magnitude 7.7 this magnitude 6.9, 15.0’ diameter open cluster is trivial for binoculars or very small telescopes.

M52 was certainly impressive in Zelda… I hadn’t expected too much on this increasingly punk night, but it was outstanding, looking more like a loose globular cluster than a galactic cluster. A bright star on the edge of the cluster’s densest section made it distinctive.

Mallas didn’t see much here with his Unitron. Other than that single bright star, the 4-inch didn’t resolve M55 or even make it look grainy. I wonder if John observed this one on a poorer night, since it seems to me I’ve had some good looks at it and considerable resolution with 4-inch telescopes.

Most open clusters aren't a challenge for the ZWO. Suze delivered a nice portrait of this one with only five minutes of exposure.

I hoped for clearing, but as 9pm came, the sky got worse. I did manage two more deep sky objects, though, the stars of our 1994 Deep South:

M74 (Pisces)

|

| Suzie did a nice job on the Phantom given the conditions |

As I’ve written many a time, the best look I have ever had of M74 was that fall of ’94 at Deep South with Betsy, my old 12-inch Dob (then in her original Meade Sonotube). This night? I’d be hard put to say M74 looked any worse. Conditions on both nights were similar, including both slightly reduced transparency and steady seeing. When AstroHopper told me I was there, the galaxy was immediately obvious in the 27mm Panoptic eyepiece. Best views were in the Happy Hand Grenade (Zhumell/TMB) 16mm 100° (78x) and the 13mm Ethos, both of which delivered mucho spiral structure. My visit to the star party this year was worth it just for this one observation.

Unsurprisingly, John Mallas found Messier 74 a difficult object indeed for his long focal length Unitron refractor (he notes it was more noticeable in his 40mm finder). Be that as it may, his drawing with the 4-inch indicates he was seeing some spiral structure, quite a feat. Kreimer’s black and white (Tri-X) photo is lovely, and competitive with modern pictures.

Little Suzie, the SeeStar S50, had to go after the Phantom Galaxy on yet another humid night. While it’s not the best image she’s ever done, she had no problem picking up the spiral arms (and a piece of photobombing space junk). I’m frankly amazed at what she did from my bright backyard.

M33

(Triangulum)

It’s difficult to say who originally discovered Messier 33, since it is (barely) a naked eye object at magnitude 5.7—I’ve certainly never seen it without optical aid. What is certain is that Messier spotted it in 1764. Its large size, 68.7’ x 41.5’ means that despite its bright magnitude, its surface brightness is relatively low, and it’s not that easy to spot the multiple spiral arms of this near face-on SA galaxy.

The Triangulum Galaxy isn’t a water dweller but was in the clear and was the other star of 1994. It was very good, with its spiral arms amazingly evident—as in “slapped me in the face” evident. I hunted around a bit before I saw the galaxy’s huge emission nebula, NGC 604, but once I oriented myself, there it was. Was it quite as starkly visible as in 1994, when I had two more inches of aperture, a more transparent sky, and younger eyes? No, but it was easy, nevertheless. One last look and M33 faded out as clouds enveloped the sky.

John Mallas’ small, slow achromat had a tough time with M33. This is just not an object for narrow field scopes (and eyepieces): “[It] is very faint and difficult in the 4-inch f/15 refractor. Instruments with smaller focal ratios will do much better.” He mentions a bright central region with nebulous patches around it and that is it.

Suzie? This is a bit on the large side for her (though I could use mosaic mode if I had the patience for that), but it’s not an object that gives her trouble.

Saturday

|

| Zelda hoping for Starlight Saturday afternoon... |

The sky did look pretty good just before astronomical twilight. Then, as I sat out on the field with Len and Annette Philpot, a bank of low, dark clouds drifted in from the south and stayed for a while. They did move off when darkness arrived, but I was nervous that this was a harbinger of things to come…

Long night? No. In the end, we got maybe 90 minutes of fruitful observing. The Milky Way was visible, but not as bright as it is at this site on a truly good evening, and deep sky objects of all types were passable but subdued. I had the feeling conditions might get worse rather than better after 8pm, contrary to what Astrospheric said, so I didn’t waste any time ticking the remaining water Ms off my list on SkySafari. Since my phone was dedicated to AstroHopper, I had the Mac on the field under the canopy. It was a real help at times. With clouds floating around, out of practice visual observer me sometimes lost his way among partially obscured constellations. SkySafari’s beautiful charts saved me every time.

The night’s haul? Modest, but not bad for an hour and a half with me giving each object sufficient attention:

M73 (Aquarius)

Chuck Messier spotted this asterism in 1780 and thought he saw nebulosity along with four stars. Herschel, however, observed the cluster and found absolutely no trace of the nebulosity Messier thought he’d seen. It was long thought that M73 was a galactic cluster, but spectroscopic studies done a couple of decades ago revealed the four stars are at drastically different distances from Earth.

This little group of stars isn’t a cluster, but it’s an M anyway. I’d somehow passed it by on the previous two evenings and wanted to get it in the log, lackluster as it is. What you have here is an asterism of four somewhat prominent stars of magnitude 10 – 12 that cover an area of 9.0’.

All

Mr. Mallas has to say about M73’s appearance is, “Messier’s description matches

what was seen in the 4-inch. Moderate magnification shows the quartet centered

in the photograph.” In other words, “Ho-hum,” which is my reaction as well.

This was obviously nothing for Miss Suze, who showed four stars in a backwards checkmark shape in a short exposure. It doesn't look much different from the shot in The Messier Album.

M30 (Capricornus)

This Shapley-Sawyer Class V globular cluster was discovered by Messier in the summer of 1764. Like the other globs he observed, it was not known to be a star cluster until William Herschel observed it. At magnitude 6.9, and a size of 12.0’, it’s not difficult for smaller scopes, though they may need dark skies to deliver much resolution.

M30, which I call “The Goat Cluster,” is one of my favorites, mainly for a curious feature, two streams of stars on the southeastern side of the cluster. More prominent visually than in photos, they suggest the horns of a goat, fitting for a cluster in the Sea Goat. They were visible on this night in the 13mm Ethos but were not as prominent as usual. For one thing, Capricornus was beginning to descend into the west, and for another, the haze was thicker than ever.

While Mallas’ Unitron didn’t pick up many stars, he still called this “A splendid object even in small apertures.” He also notes the cluster’s “unusual” appearance, which I take to mean the star streams mentioned above. Kreimer’s photo shows the “goat horns” remarkably well.

Despite conditions, the girl did a nice job on the Goat, her image showing the horns clearly.

|

| Our final night started out promisingly--but didn't stay that way. |

Prolific observer Pierre Mechain ran across this magnitude 8.9 SA galaxy in 1780. Of course, he didn’t know anything about galaxies and told His friend Charles he had discovered a nebula down in Cetus. This small (7.1’) object is easy to see thanks to its intensely bright center. M77 is known to be an active Seyfert galaxy and a strong radio source (Cetus A). It is also on Halton Arp’s list of peculiar galaxies.

Cetus A has never been a challenge in any scope for me. This was one of the few that I could see easily with my 4-inch f/10 Newtonian from the backyard of the old Chaos Manor South downtown. On this evening? Bright. Fascinating. What you see is a large, nebulous envelope surrounding a bright central region with a disk and spiral arms. I bumped up the power to over 200x with the 5.7mm ES eyepiece in hopes of seeing that spiral structure, and I did get a glimpse or two of it on a night that was winding down.

Mallas was impressed with M77, calling it “One of the best objects for viewing in small apertures.” Not surprisingly, the Unitron didn’t show any spiral features, He does, however, seem to see that the central area of Cetus A is different from that of other galaxies.

The problem with M77 for the smartscope is that it's a little small, and there is a limit to the central detail you can expect. Nevertheless, Suzie did her best, and I've taken worse picture of this galaxy.

M75 (Sagittarius)

It’s not clear whether this one should be credited to Mechain or Messier. It is known that Charles at least confirmed Mechain’s observation in October of 1780. Once again, it was The Man, William Herschel, who first resolved this Magnitude 8.6 cluster. How to describe this glob? Tight, small, relatively bright. It’s a Shapley-Sawyer Type I, the most highly concentrated class. At only 6.8’ across, it is easy to see.

I got to this one a little late; it was low enough that it wasn’t quite as bright as it should have been in a 10-inch telescope. Which doesn’t mean it wasn’t prominent and easy—it was. However, what I saw was nothing more than a grainy fuzzball with a reasonably bright core.

His 4-inch presented John Mallas with an M55 that was just a nebulous ball with a bright core. In other words, not much different from what I saw in my 10-inch. I was, however, able to see a grainy texture suggesting resolution, which Mallas didn’t detect in his 4-inch.

Small, low, on the dim side. Well, at least Suze and I got something.

And then more clouds came. I waited ‘em out, and they began to thin (some) around 9pm, but only some. Astrospheric had begun talking about “mist,” and it now looked to me as if the clouds hadn’t really left; they had just reduced their altitude. As a check, I sent Zelda to NGC 891, the famous edge-on galaxy in Andromeda. Initially, I thought AstroHopper had missed, but I finally spotted a dim, slightly elongated glow in the field center. I’ve seen this galaxy better with an 8-inch SCT. NGC 7331 was about the same, there, but lackluster. I could see it with fair ease, but the “deer” accompanying the Deer Lick Galaxy, the small galaxies in the field, were invisible.

Time

to throw the big switch? Nope… I wanted to try out my wonderful prize!

Your aged Uncle, who rarely wins anything astronomical, had won a TeleVue

eyepiece at the Saturday raffle drawing! And a very special (and specialized)

TeleVue it was, the 55mm Plössl. This is an eyepiece I’ve thought about buying

for years, but I have always hesitated. Mainly thanks to that enormous exit

pupil, which is a bit large even for my SCTs. I had one now, though, and I

was going to try it out on an f/5 telescope.

M45 (Taurus)

|

| Wow! I won something! |

First object for the 55mm? Why M45, of course. It was quite something to encompass most of the Pleiads in the field of a 10-inch telescope. Exit pupil, exit schmupil; I even convinced myself I saw a trace of the Merope Nebula (uh-huh).

John has a lot to say about the Pleiades, but mostly background and technical information as it was known well nearly 60 years ago. His big Unitron was, after all, a very narrow instrument for this object. He does tell us of seeing the Merope Nebula with his scope from the dark skies of Arizona, though, which is a master class observation.

I needed to post this article before I was able to give Suzie a shot at M45, but in the past she’s done a good job on the Daughters of Atlas.

Saturn

You can bet I visited Saturn before giving up the ship. With his rings near edge-on, some would say he isn’t quite his normal spectacular self. He is to me. This is the way I saw Saturn with a telescope for the first time, with my Palomar Junior in 1966. On this night, seeing was good; the shadow of the rings across the disk razor sharp in my 4.7mm Explore Scientific 82° ocular (265x). Coolest thing? Little Enceladus was visible just above the plane of the rings and almost seeming to touch them.

Fun is fun but done is done. The sky didn’t slam shut; it just faded away as it got damper and damper. I covered the faithful Miss Zelda and headed for the Lodge. I was sad not to be able obey the rule my old friend, Pat, and I established many a long year ago, “No going to bed before M42 is up high enough to fool with,” but there was nothing for it. Shining my flashlight into the air produced a cone that looked like the Bat Signal.

Sunday morning, Dorothy and I departed before breakfast, wanting to get home and check on the cats. It wasn’t pleasant loading sopping wet gear—it seemed more like the product of a downpour than a dew fall—but our simple field setup meant we were on the road in record time.

The

verdict on DSSG 2025?

Attendance was 62, nowhere near what it was in the golden age of the 90s - 2000s

but improved over the last years at its previous location. I predict the Deep

South Star Gaze is on the way back up and has many more good years ahead of it.

Our personal experience? Despite the weather, it was just great, and

we plan to be back for 2026, I am also hoping to be at the spring edition of

the star party, the 2026 Spring Scrimmage, which will also be held at

Feliciana again.

Totals: 17 Down 93 to go…

Nota Bene: You can see many more pictures in the DSSG 25 Photo Album on Unk's Facebook Page...Wednesday, October 29, 2025

Issue 621: The Messier Project 2... M15, M31, M32, M110, and M33.

Before we hit the leading edge of the autumn Messiers, muchachos, let’s get one thing out of the way: Yes, I did see comet Lemon (c/2025 A6). I didn’t observe the visitor in any kind of elaborate fashion, though. I didn’t even give my Richest Field Telescope, Miss Tanya, a shot at it. Weather and my health (I’ve been down with a bad cold/some kind of bronchial infection) impelled me to keep it simple. When I decided I’d better get to the comet before she got into the trees—Lemon is moving south at a good clip, now—I grabbed my beloved Burgess 15x70 binoculars.

These glasses, purchased at the 2003 ALCON in Nashville where I was a speaker, have long been my goto when I

want reasonably wide fields, and a little power—both in magnification and light

gathering—in a compact, hand-holdable package. They are also high in optical

quality, and I simply cannot believe the late Bill Burgess sold them to me for a

mere fifty bucks!

Anyhoo, out onto the deck I went. The Moon had waned away,

so that was not a factor. The factor was the race between altitude and

position. Every day I waited put the comet a little higher in the sky, but

every passing day also put it farther to the south. Chaos Manor South’s

southwestern sky is almost completely obscured by trees, so, I didn’t wait too

long. On my chosen evening, I had to do a little scanning around, but it wasn’t

long before I turned up Lemon. At first as just a fuzzy “star.” A little

staring, however, revealed a delightful wee tail!

That, friends, was the extent of my adventures with the

comet. I didn’t image it, not “even” with a smartscope; I just didn’t feel up

to it. I was glad, however, to have seen our visitor from the outer depths and

have enjoyed looking at the lovely pictures y’all have taken.

But onto the main

course, the next batch of Ms. As I mentioned in the first installment, this

time we’ll be taking them on constellation by constellation rather than by

numbers. The constellations for this evening are few but lustrous: beautiful Pegasus

the Flying Horse and Andromeda the Maiden. They are the heralds of the star

pictures of fall and are renowned both for their beauty and for the ease at

which they can be picked out even by novice observers.

So, let’s go. The instruments for this bunch? I’d like to say

Zelda, my 10-inch Dobsonian, was one of them, but ‘twas not to be. While, as I

told you last time, I can still get Z into the backyard safely if I am careful

and take it slowly, my Bad Cold meant I didn’t feel up to lugging her sizeable self

into the back forty. So, the visual telescope would be my 6-inch SkyWatcher Dob. What’s that? Her name? Let me ask; I haven’t thought to enquire. OK, she’s says,

“Patty.” Why Patty, I don’t know.

But that is what she said, and a scope should know her own name, shouldn’t she?

The imaging telescope? The SeeStar, Suzie, natch. She is really no trouble at

all even when I’m not feeling so hot.

Messier 15

There is no doubt globular cluster M15 in Pegasus is a grand

sight. One of the best globs in the northern sky. However, that comes with a

caveat. In addition to its lovely appearance as a ball of tiny stars, this

cluster is famous for its very tight, preternaturally

bright core. The cluster isn’t the densest one on the Messier list, but at

Shapley-Sawyer Type IV, it’s dense enough, and the brightness of that core (a

feeding black hole is thought to lurk there) makes it tough for smaller scopes

to resolve. On the plus side, M15 shines at magnitude 6.15, making it at least

a near naked eye object from dark

sites. It subtends an impressive 18’0” of sky.

So, to the Horse’s Nose Cluster me and Patty went. What did

we see? With a 30mm finding eyepiece in the focuser, what we saw was probably

not much different from what Jean-Dominique saw on that Italian evening those long

centuries ago: a bright fuzzball with a brighter center. Seeing more required

more magnification, and as much as I like Miss Patty, that is not easy for her.

Her optics are good, but at 150mm f/5, you need a short focal length ocular. Luckily,

I had one, a 4.7mm Explore Scientific wide-field eyepiece (160x) that I won at

the last Chiefland Star Party I attended. When I looked into it, I was

gratified to see the spray of tiny, tiny stars that surrounds that blazing

core.

Famous observer

(obviously not moi) impressions? Tonight,

we turn to Walter Scott Houston.

He’s often described as “the dean of deep sky observers.” So frequently, in

fact, that that has come to sound like a cliché. It is nevertheless oh-so-true—and

how. What did Scotty have to say about M15 in one of his “Deep-Sky Wonders”

columns?

The view of M15 is

impressive with anything from binoculars to the largest telescope. My 4-inch

Clark refractor at 40x shows M15 as a slightly oval disk, more luminous in the

center, with edges just beginning to break up into individual stars. Increasing

magnification enhances the view, and at 200x stars at the center of the cluster

start to be resolved.

Which is right on the money as far as I am concerned.

Then it was Suzie’s turn. Despite the Seestar smartscope’s 50mm

of aperture and 250mm focal length, the girl brought back a very pretty

rendition of M15. That said, I need to let my longer focal length Smarty-scope,

Evie, the 4-inch Evolution reflector, have a go at M15 before the season is

out.

Messier 31

There are few objects in the deep sky I’ve had as much of a love-hate relationship with as M31, the Great Andromeda Galaxy. The hate stems from my disappointment as a young’un with one of the very first deep sky objects I observed. When I finally ran it down, what was in the 1-inch Kellner eyepiece of my 4-inch f/11 Palomar Junior Newtonian? A big, bright blob that pretty much filled the field. Extending southwest to northeast from the blob was a stream of dimmer nebulosity that I guessed represented the galaxy’s disk. What? No spiral arms?! Little Rod expected spiral arms.

Despite M31’s closeness and brightness, it was no wonder I didn’t see spiral structure. This is a huge object, a blazingly bright (magnitude 3.4) SA galaxy that extends across a whopping 3.1 degrees of sky. Not only did its size make it a challenge for my small, long focal length reflector, the galaxy’s rather shallow inclination to us—77°, not edge-on, but not far from it, makes it difficult to detect signs of spiral structure in any telescope. While M31 was first recorded by Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi in his Book of Fixed Stars in the 10th century, there are apparent references to it going way, way back.Certainly, as the years rolled by and I acquired more

suitable scopes for M31 and learned how to use

them, I came to see a lot more in M31. That included the dark lanes that are

the signature of spiral arms, a giant star cloud, a tiny near-stellar nucleus,

globular clusters, and more. However, most of those sights are reserved for

dark sites. What did my 6-inch pick up from the backyard of suburban Chaos

Manor South?

There was the blob, naturally, that enormous central

bulge that filled my field with milk. I struggled for at least a hint of the

compact nucleus but did not see a trace—not surprising, as that is an object

that often needs 10-inches and almost always needs a dark sky. The disk? I

didn’t expect dust lanes, but wondered if the giant star cloud, NGC 206, that

lies 49'0" southwest of the galaxy’s center might be visible. I convinced

myself I saw something in the correct position, but that may have been

averted imagination. M32 and M110? See below. If I’d been feeling a little

better, I’d have popped in the house for those Burgess binoculars, which are a

more appropriate instrument for M31 than even a short f/l 6-inch reflector.

Let me say that you can pick a far worse scope for M31 than a 6-inch f/5 at 25x with a 30mm

ocular. The problem was the light pollution-scattering haze of

autumn that is almost always with us in the weeks before cold fronts begin to

clean things out.

Scotty’s thoughts? He just isn’t bullish on Andromeda,

remarking that it is often a disappointment. That is certainly true, but I do

take issue with his claim that spiral structure “Probably cannot be seen in

amateur instruments.” I would say the aforementioned dark lanes are certainly the

galaxy showing that spiral structure. He does admit these dark lanes can be

seen in modest scopes but does not connect them with “spiral structure.” That

quibble aside, yes, Scotty nails it again. Andromeda is more famous for its

brightness (I was able to see it with ease as a fuzzy star from the backyard of

the original Chaos Manor South downtown) and what it represents, the closest large galaxy to us, than how it looks in

the eyepiece.

How did The Suze do with Andromeda? M31 was the first object

I essayed after ZWO implemented “mosaic mode” with the Seestars. When you

engage that, the scope takes a picture, moves, takes another picture, etc.,

making it able to frame objects too large even for its short focal length. I

was pleased by the results, but found the mosaic business to be a pain, taking

hours to complete and often not

completing due to the target getting into trees or other obstructions before

all the shots were done. Still, it’s a nice tool, and Suzie returned a pretty

good Andromeda. The bottom line is that this bright and big and obvious object is much more difficult to image than you would think.

M32

This little E2 elliptical is the most prominent of

Andromeda’s retinue of satellite galaxies. While it’s “only” magnitude 8.2,

it’s small, 8’30” x 6’30”, and appears bright indeed. If you’ve successfully

located M31, there’s no “finding” to M32; it stands out like a sore thumb about

25’0” south of the core of M31. Visually, it’s just outside the disk of its

parent galaxy. Who discovered the little guy? That is attributed to Guillaume

Le Gentil in 1749, but I’d guess whoever it was who first turned a

telescope to M31 saw M32; it would seem impossible to miss.

For me, M32 has always been, “Yeah, nice, adds to the beauty

of M31” and that is about it. There’s just not much to see here; it’s a

bright, featureless elliptical that appears completely round. At magnifications

of 150x and up, it should be easy to see the center is surrounded by a dimmer envelope

and… End of story. Scotty? He has little to say about the elliptical,

merely noting that it can sometimes be mistaken for M110.

I didn’t bother to do a separate image of M32; there’s just

not much reason to do so. The Seestar’s M31 picture shows the small companion

well enough. Frankly, large telescopes and long exposures don’t get you much more

with M32. They can show the elliptical’s elongation, but that is about it.

M110

Like M32, M110 is a satellite galaxy of Andromeda,

but it is at least a somewhat more interesting one. It’s an E5 with a magnitude

of 8.1 like M32, but is considerably larger at 21’54” x 11’0” and looks much

dimmer—it can be rendered completely invisible in the suburbs by sky conditions

that allow M32 to shine on. It’s also considerably more distant from M31’s

center, lying 36’19” to the northwest. The discoverer? Messier never added this

elliptical galaxy to his list, though he did include it in drawings he made of

M31. In my opinion, then, the credit should go to Caroline Herschel who

observed it on August 27, 1783.

Scotty doesn’t have much more to say about M110 than he does

about M32, just that it is the next closest satellite galaxy to M31 after M32,

the remaining companions being to the north in the Cassiopeia area.

As for The Suze? She did a rather nice job on M110, as you

can see here in this crop from her main M31 images. Maybe I’m fooling myself,

but I believe I can see signs of that subdued detail in M110. It’s enough to

make me want to turn the Unistellar smartscope loose on M110 some evening.

M33

M33, the Triangulum

Galaxy, is another object that really fired my imagination as a kid observer. It was obvious to me from pictures that,

unlike Andromeda, Triangulum should show spiral arms. Given the galaxy’s inclination

angle of 50°, I figured it

should be duck soup to see some arms. As I soon discovered after multiple nights

observing it in Mama and Daddy’s backyard, ‘tis not so. While this

magnitude 5.7 SA galaxy can be spotted with the naked eye from darker sites,

that is not an easy task. With a telescope, especially a longer focal

length one, M33 is almost as difficult. That magnitude 5.7 light is spread

out over an area of 1°08’42”

x 0°42’00. I was lucky to see anything at all. The recipe for success if you want spiral

arms? Dark skies and a 10 – 12” telescope at f/5 or below.

Historically, while

a naked eye object (if only marginally), it does not appear to have been recorded

before the age of the telescope. When it was first noticed, it wasn’t by

Charles Messier, but by Giovanni

Battista Hodierna in/around 1654.

How did me and Miss Patty fare with the Triangulum Galaxy? Not so hotsky. The best we could do on a semi-punk night (because of the haze) was detect a subtle brightening in the field in the correct spot. It wasn’t even clear we were seeing an oval patch of nebulosity, just a generalized hazy something in the field. I tried a UHC light pollution filter in hopes of seeing NGC 604, the enormous complex of nebulosity in one of M33’s arms, but no dice. I have seen the nebula with fair ease with the 10-inch Dobsonian from a site on the edge of the city-country transition zone, but that was on an outstanding night.

As you can imagine, ol’

Scotty has a lot to say about Triangulum—despite my near failure with it

on this night it really is one of the premier galaxies for Northern Hemisphere

observers. I urge you to read his column “The Great Triangulum Spiral”

for yourself, but to sum up, the Old Man mentions both the difficulty some observers

experience trying to see even a hint of M33 on the wrong night or with the

wrong scope, and his delight at not just having seen the spiral, but of having

conquered NGC 604.

The Suzie girl had

no problem with M33. The picture she returned impressed me quite a bit. It’s

not quite the equal of the M33 I got with one of my APO refractors and my old EQ-6

mount one dark night at the Deer Lick Astronomy Village some years ago, but it’s nice and the color balance is better. And, hell, it was

taken on an average night from my bright backyard!

And the Messier

road goes ever on. The

autumn objects hidden among the subdued stars of the “water” constellations

await us. But that’s for another time. The night has grown old, Hercules has

plunged into the west, and me and my faithful telescope have covered enough light

years for one fall evening.

The Bottom Line: 11 down 99 to go…

Nota Bene: If you’d like to read Scotty’s “Deep-Sky

Wonders” columns, you have a couple of options. If you have access to the

original magazines, you’ll find him in just about every issue from 1946 to

1994. Don’t have all those old magazines? If you’re lucky, you glommed onto the

Sky & Telescope DVDs that were

sold some years ago. These contain the entire run of “Deep-Sky Wonders.” Got

neither? You can get an excellent sampling in the compilation volume edited by

James O’Meara, Deep-Sky Wonders.

The Passing of a Giant…

I received the

shocking news that optical genius Al Nagler, founder of TeleVue, passed

away last Sunday, the 27th of October. Yes, I was shocked. I

shouldn’t have been—after all, Al was mortal like all of us and was getting up

there in years. But it’s just hard to imagine an astronomy without Nagler. What else

is there to say than that Al Nagler was one of the people who didn’t just leave

their mark on astronomy but changed it forever. There are two eras in

eyepieces, “Before AL” and “After Al.” Nuff said.