Sunday, August 09, 2009

My Favorite Fuzzies: The Lagoon Nebula

Messier 8 is a fave of mine. Has been for years. But it sure didn't start out that way. In fact, the first time I had a look at what had been preached to me as "the other Orion Nebula,” I was badly disappointed.

That, however, is, in typical Uncle Rod fashion, putting the cart before the horse. What has brought M8 to my mind (such as it is), anyhow? It began with one of my long-time astronomy friends, Tom Wideman of Texas. He sent me an email the other day reminding me of the fun we’d had at the 2001 Texas Star Party. That got me to thinking about the first time I met Tom, a couple of years previously at the 1999 TSP. Which led me to reminiscing about all the great things I saw that year. Including a scary-good M8.

Sound convoluted? Yeah, I know it does, and that’s actually just the end of my M8 story, which began more than thirty years before in Mama and Daddy’s backyard...

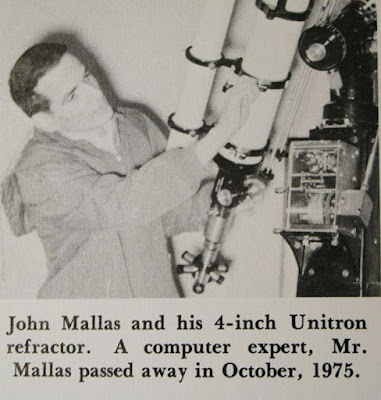

Before turning down that path, though, why don’t we start with Just the Facts, M’am as in “What is the Lagoon Nebula?” If you want "succinct," I suggest you turn to one of my favorite books, John Mallas and Evereid Kreimer’s A Messier Album. My relationship with that little volume is a story in itself, and I hope you’ll indulge me and let me say a few words about it before we get down to brass tacks.

‘Twas a sunny Saturday afternoon (had to be) in the spring of 1967 down in The Swamp. Li’l Rod, who was, oh, mebbe 13 at the time, was getting antsy. It was that time of the month. You know, time for the arrival of Sky and Telescope (back in the old days, it was indeed "and," not the modern &). You sprouts can scarcely imagine what a big event that was in the average young amateur astronomer’s life way back when.

Then, unless you were lucky enough to live somewhere where there was an active astronomy club that welcomed kids (usually in the form of a "Junior" section of the club), the coming of the new Sky and 'Scope was about all the exposure you got to amateur astronomy month in and month out besides your public library’s (usually small) collection of astronomy books, and talking astronomy with your buddies who shared your obsession—but who were likely as ignorant about it as you were.

So it was that when Sky and Telescope time drew nigh, young Rod invariably stationed himself in Mama’s living room (despite her hard looks) to keep a weather eye on the mailbox through the picture window. “Here comes Mr. Postman! He’s stopping…there’s something big going in the mailbox! Yay!” Out the front door at a run. That "something big," if’n I was lucky, would turn out to be a manila envelope.

In those days of yore, you see, Sky and Telescope was not only presented in a larger (if thinner) format, 8.5 x 11.5, it was mailed in an envelope emblazoned with that wonderful postmark, “Cambridge, Massachusetts.” When Rod scored like he did on the afternoon in question, the rest of his day was set. If the sky happened to be clear, so was his night. Even if there wasn't a good article about observing (with Scotty's, Walter Scott Houston’s, column in every issue, there usually was), just getting the magazine impelled me to heights of enthusiasm, and the Palomar Junior was set up in the backyard by sundown if there appeared to be the slightest chance for clear skies.

|

| Sky AND Telescope. |

Right on page 285 (the magazine used volume page numbering back then) in the prestigious front was an article in what, it appeared, would be a series. An article aimed right at us amateurs, John Mallas and Everid Kreimer’s “A Messier Album.” Mr. Mallas handled the writing chores, and Mr. Kreimer did the photography. What would this series be about? Paragraph two made that plain, “We will present a photograph, often a drawing, a finder chart, and a description of the visual appearance of each Messier object, from all-new observations.”

YEEEHAW! The demigods who resided at Harvard College Observatory must have been reading my mind. I was hot on the trail of the Messiers for the first time and needed help. What was easy? What was hard? How would these things look through the eyepiece of my Pal Junior? How did I find them (I was still struggling with Norton’s Star Atlas while saving my pennies for the much better Skalnate Pleso)?

Starting with M81 and M82, the subjects of the first installment, these two guys helped me catch 'em all over the next few years. Well, almost all. Despite their help, a few of the hardest ones like M101 and M74 continued to stymie me for some time. Anyhow, from that beginning to the end of the series, “A Messier Album” became, with “Deep Sky Wonders,” my favorite part of the magazine. Actually, I often found "Album" more helpful than Scotty’s column, since he was sometimes way beyond my puny abilities.

About a decade later, Sky Publishing wisely collected the “A Messier Album” columns into a book, The Messier Album. I didn’t rush out and buy a copy, though. I was (I thought) beyond the Messier by then, and I still had my magazines. I never forgot John Mallas and Evereid Kreimer, though, and one recent afternoon while browsing Amazon.com, I was taken by nostalgia, and on the spur of that ordered a copy.

When it arrived, I was genuinely surprised. It was every bit as useful as I remembered it being. Mallas’ prose is clear and concise, and though usually unadorned, it is descriptive when it needs to be. His drawings, done with a 4-inch Unitron refractor, can look a little weird and fanciful in daylight, but under the stars with a dim red light they look remarkably like what I saw through my 4-inch Newtonian, and will resemble what any small or medium aperture telescope will deliver today.

|

| This classic is still easily available (used) |

Now…ah…where was I? Oh, yeah, M8. If you want short and sweet, Mr. Mallas says:

Commonly known as the Lagoon Nebula due to the great line of obscuring matter that crosses its center, M8 is similar to M20, which lies only 1.4-degrees to the northwest. It is about 60 by 35 minutes of arc in size. The nebula may be 2,500 light-years distant, but that is uncertain.As you might guess, in the intervening forty plus years our distance estimates for this deep sky object have been revised—though they are still somewhat “uncertain.” Most I’ve seen put it significantly farther away than John thought, with the cloud now being assumed to be more than 5,000 light-years out in the dark.

We can amplify a little bit on Mr. M’s barebones summary, too. The Lagoon is an emission nebula, a star-forming region that is being excited to illumination by the massive blue - white stars hidden within its folds. In images, at least, M8 is a little bigger than the 60 x 35-minutes Mallas mentions, with the nebula stretching at least 90 x 40-arc minutes. In addition to its Messier number, this wonder bears the additional catalog designations NGC 6523, NGC 6526, IC 1271, Sh 2-28, and LBN 25. How bright is it? It’s close to magnitude 5, which compares quite well with the Great Orion Nebula’s integrated magnitude of 4.0.

John Mallas' enthusiastic description of M8 as “one of the showpieces of the heavens,” made me lust for this thing as soon as I read its Album entry. I loved Orion, and the fact that there might be an “almost as good” in the summer sky just seemed right to me. As soon as Sagittarius got high enough in the early summer heavens for me to have a look at it before my bedtime (10:30 if I was lucky), I was out there and after it. I found a spot near the house on the southwestern side of the yard where I had a reasonably good view of the southeastern horizon and got the Pal Junior set up.

Although Mallas and Kreimer furnished a semi-useable (by today’s standards) finder chart, I soon realized I wouldn’t need it nor would I need my copy of Norton’s, which I’d dragged outside, too. I pointed my Pal at the Sagittarius Teapot’s spout and began scanning up along the Milky Way—or at least where I thought the path of the Milky Way was; it was mostly invisible in my hazy and humid suburban skies. I was quick to sight my target; it stood out clearly as a fuzzy "star," even in my puny 22mm finder. Centered it dead in the cross-hairs, inserted my “1-inch” focal length Kellner, and had a peep.

|

| Mallas' M8. |

What I was seeing was actually not too much different from what Mallas showed in his drawing: fuzzy disconnected patches. In the Album’s sketch, these patches tended to define the dark “lagoon” lane considerably better than what I was seeing, though. To my eye, this was not even close to M42. Now, if M8 had looked like the huge globe of nebulosity in Kreimer’s photo, that would have been a pony of a different shade. But it didn’t. I put it all down to over-exuberance on the part of John Mallas and moved on to other objects. Wasn't the Swan Nebula around here somewheres?

Obviously, today I consider The Lagoon Nebula as good or better than Mallas and Kreimer thought it was. It is one of the premier wonders of the southern (or northern) sky. Why did my opinion change? Time and tide, muchachos, time and tide. Or, to put it another way, I learned how to observe, where to observe, and what to observe with.

Learning to observe is the first hurdle for any novice deep sky observer. I don’t just mean tricks like using averted vision or jiggling the telescope to bring out faint objects. The even more mundane has to be mastered before you can see well through a scope. Where do you put your eye? Do you jam it up against the eyepiece or move it back a little bit? Is it better to sit down while observing or stand up? Keep both eyes open or squint one? These things deserve a separate blog entry of their own, so, for now, I’ll just say as my time in the hobby slowly ticked on, I slowly learned how to look.

A related issue I don’t hear discussed often, but one I’ve preached about in the past, is the seemingly simple question, “How long do you look at something?” As a kid, I rarely gave a DSO more than a glance if it didn’t knock my socks off at first blush. “M82? Looks like a dim little oval. What’s next.” That took, maybe, one or two minutes. As I matured as an observer, I began to find that—big surprise—the more I looked, the more I saw.

If I observed M82 for half an hour using a variety of magnifications, it became much more than a dim oval glow. The same went for the Lagoon. The more I looked, e’en under less than optimum Possum Swamp skies, the more the patches of nebulosity began to connect themselves into a big cloud like in the Kreimer pic. I developed a rule I’ve done my best to stick to over the years: If an object is worth observing, it is worth observing for half an hour.

Want to put that on steroids? In addition to staring at a DSO for an extended period, try drawing the thing. Yeah, yeah, I know “But Uncle Rod, I CAN’T DRAW.” Hey, I’m not asking you to duplicate Woman with a Parasol, just to record what you see in some fashion. I’ve given some pointers for that in the past, but you know what? It really doesn't matter how you draw. The important thing is not the finished product (though, as your skills improve, and they will, you will come to cherish your artworks) but the process. By observing carefully and trying to draw, to at least create an impression of what you see, you will be amazed at how much more you will pull out than you normally would. The finished sketch is just an added bonus.

Every bit as important as “how” is “where,” where you observe from. Back in the day, my folks’ backyard had some things going for it as well as some strikes against it. The good was that, before 1970, light pollution was minimal. There were mercury lights, but just a few, usually on corners. Also good was my latitude, 30-degrees north. You can’t expect to ever get a really good look at Sagittarius’ wonders if they are always down in the worst horizon garbage.

Against me was Possum Swamp’s usual summer weather pattern: fierce storm-bringing lows tag-teaming with stagnant high-pressure domes. The latter meant that even when it was clear, the sky was often more like milk than velvet. Great for planetary observing at high power. Deep sky touring? Not So Much. There wasn’t a danged thing I could do about that situation. About all I could really do was listen to the TV weatherman and hope for a storm front to pass and bring clear, clean, dry skies. Alas, that didn’t happen often in the summertime. Take that humidity and couple it with even minimal suburban light pollution, and it is a wonder M8 looked as good as it did.

I didn't really get a good look at the Lagoon until I moved back to Alabama in 1979 after an absence of four years. Before long, I'd found a club with a dark observing site and a local star party, the Deep South Regional Star Gaze. Nothing is hurt worse by light pollution than nebulae and being able to observe the Lagoon from the dark (in those days) skies of the DSRSG at Percy Quin State Park in the deep piney woods of Mississippi was, to put it mildly, a revelation.

What you observe with contributes to the cause, natcherly. Going from 4 and 6-inch Newtonians to an 8-inch Newt and then an 8-inch SCT made a heck of a lot of difference. What probably made almost as much, though, was my progression from the uncoated Ramsdens and Kellners of the 60s to the much better Erfles and Plössls of the 70s and 80s and, finally, to the Panoptics and Naglers of the 90s (and lately, to those 100-degree AFOV oculars from Explore Scientific and TeleVue). I still think aperture means the most, but, as Uncle Al likes to preach (natch), eyepieces are a big deal. What makes modern oculars superior, even more than their coatings, is their wide Apparent Fields of View (AFOV). That allows us to up the magnification, spreading out any background glow, while keeping the true field wide enough to make big M8 look good.

The final piece of the puzzle was the UHC and OIII light pollution reduction (LPR) filters. Lumicon’s filters, which came to prominence in the 80s, helped almost as much as better oculars. If M8 was good under dark skies with a decent eyepiece, it was spectacular with the addition of an LPR filter.

Put it all together and what did I have as the 1990s came in? In my C8’s eyepiece, the nebula stretched from east to west, from the eastern tendrils (seemingly) enwrapping the star cluster, to a starkly dark lane, to a big ball of nebulosity on the west side. Upping the power to 150x or so brought out hordes of “little” stars, not unlike in the areas bordering M42's “fish mouth.” Going higher still in magnification, to 200x, caused the heart of the nebula, the Hourglass, a brighter patch shaped like the ensign on a black widow’s back, to shimmer into view. I came to rate M8 very highly. It was a marvel, a wonder. I still didn’t think it was in shoutin’ distance of M42, though. It would take a few more years before I came to believe that.

Yeah, I thought I had seen The Lagoon. But I hadn’t. Not until I paid my first visit to Prude Ranch’s legendary Texas Star Party. One night about three evenings into the star party, I was feeling a bit weary. TSP had been incredible thus far. One crystal clear black-cat-at-midnight-dark night after another. It was mid May, and I don’t believe there had been appreciable rain in the Fort Davis area since the previous November. I was hitting it hard, chasing things like the Twin Quasar night after night. I finally needed some rest and some spectacle. I decided to spend at least part of Tuesday’s observing run gaping at Messier showpieces. Looking south, the teapot was boiling, the steam pouring out of the spout being represented by the blazing Milky Way. I headed that-a-way.

What did M8 look like in my 12.5-inch Dobsonian with a 12-mm Nagler and an OIII filter? It’s hard to describe even now. The best I can do is to say it was a towering thing that, as I moved my eye around the field, seemed to stretch over my head and on forever. Nebulosity was everywhere, in clouds, patches, and tendrils. The dark lane, the Lagoon, wasn’t that dark anymore. Its interior showed streaks of glowing cloud, like rapids in a great dark river. Removing the filter brought countless infant suns to life, and they dazzled me. I finally had to pull away from the Nagler for a moment. I had begun to feel vertigo, as if I were being sucked into the eyepiece, into the depths of the great misty landscape. As good as the Great Orion Nebula? Pardon me if I commit heresy: it was better.

What’s the takeaway? It’s like my old granny used to caution me, “Boy, don’t be hasty. Slow down and things will work out directly.” “Directly” in southern speak is a wonderful word. It can mean “ten minutes” or “ten years.” But the sainted Pearlie Pierce’s meaning is clear: some things need patience above all. There are objects I’ve seen a hundred times. A thousand times. Most of those times most of ‘em were distinctly ho-hum. Then, on a special night from a special place, they come to life.

You have to have the patience to keep coming back to supposedly familiar objects night after night. Eventually eveything will, if you are lucky and doing it right, come together. M8? I have never again seen it like I did that one time. It’s been close once or twice, but never quite, though I keep on trying. Once, however, is enough, it turns out; that spectacle is locked forever in my heart.

2018 Update

Not really much need be updated or added to this one, which is one of my favorite "observing" entries. My only comments concern a couple of gear changes in the intervening years, not the wonderful Lagoon Nebula itself.

The biggest change equipment-wise has been that I've turned away from TeleVue eyepieces. Oh, I still think they are great. Pretty likely the best in the business. Of course you certainly pay for that "best." Nevertheless, I'd still be biting the bullet for their 82-degree and 100-degree eyepieces save for two things. First, I'm retired now and am on a semi-fixed income, and its hard to justify the purchase of another expensive eyepiece. The second and biggest reason, though? I found a great (and significantly lower priced) alternative.

Are the Explore Scientific 82 and 100-degree eyepieces quite as good as the TeleVue Ethoses and Naglers? Some will say, "not quite." I'm not sure about that. To my aging eyes, the difference is indistinguishable. And, in some ways, aging eyes are challenged more by poorer eyepieces than younger ones are. As we age, our eyes become less able to find a nice median focus for stars in the center and the edge of the field, and in poorer eyepieces, stars at the field edge just look worse.

Years ago, just as the two companies were releasing the new 100-degree marvels, my friends and I did a shootout between the Ethoses and the (near) equivalent focal length ES eyepieces. I couldn't tell the difference. While I've hung onto my Ethoses, I won't buy more. I've also turned to Explore for their 82-degree oculars. They are also more than good enough for me, and my wallet thanks me.

I've also switched brands of OIII filters. I used my old (mid-90s) Lumicon OIII for well over a decade. But looking through more modern filters, it was clear my OIII, which I purchased at the 1996 Mid-South Star Gaze, had been outclassed. What I use now is Thousand Oaks (2-inch) and Baader (1.25-inch). I am very happy with both.

Comments:

<< Home

Hi Rod,

I've had the "oh my gosh" moment only once. My daughter had a friend for an overnighter and I thought why not set up the 9.25 and show them Saturn. It had been raining that day, but there were some nice sucker holes. Needless to say it was wonderful! The skys were steady and the rings were distinct. Both divisions were easily visible and even the banding in the rings were noticable. Banding on the planet was amazing. I've only seen it that well in "good" pictures and this was through the EP. Not to mention all the moons that were easily seen. No waiting for it to go steady, it was always steady. One for the 'ol memory bank.

Darren

P.S. The kids weren't that impressed, I guess NASA will always do it better then me :)

Post a Comment

I've had the "oh my gosh" moment only once. My daughter had a friend for an overnighter and I thought why not set up the 9.25 and show them Saturn. It had been raining that day, but there were some nice sucker holes. Needless to say it was wonderful! The skys were steady and the rings were distinct. Both divisions were easily visible and even the banding in the rings were noticable. Banding on the planet was amazing. I've only seen it that well in "good" pictures and this was through the EP. Not to mention all the moons that were easily seen. No waiting for it to go steady, it was always steady. One for the 'ol memory bank.

Darren

P.S. The kids weren't that impressed, I guess NASA will always do it better then me :)

<< Home