Sunday, May 15, 2011

Welcome to the Stellarium

If’n you have even a nodding acquaintance with the world of astronomy software, I don’t have to tell you what a “Stellarium” is. With Cartes du Ciel, it’s become the most popular freeware astronomy application. Some folks like it even better than Cartes, though it is aimed at a somewhat different audience.

If’n you have even a nodding acquaintance with the world of astronomy software, I don’t have to tell you what a “Stellarium” is. With Cartes du Ciel, it’s become the most popular freeware astronomy application. Some folks like it even better than Cartes, though it is aimed at a somewhat different audience.Cartes du Ciel is great. It can interface with other programs like Deepsky and RTGUI, can go incredibly deep, and is all many deep sky obsessed amateur astronomers need or ever will need. That’s the good, but like every other piece of software, Cartes ain’t good at everything. It’s a little slow to load for use for quick “what’s up” looks at the virtual sky. And, while the updated display of CdC version 3.0 looks good, it can’t compete with the likes of Starry Night and RedShift.

I like to have a planetarium program for spur-of-the-moment sky checks. Fer instance, I want to know if Saturn is high up enough RIGHT NOW for me to tote our StarBlast mini-Dob onto the front porch for a 5-minute peep at the ringed wonder. I do not want to cool my heels while the program loads. Or push buttons. Or look at menus. I want a program that is quick like a bunny. That leaves out the heavy-hitters, including big names like Starry Night Pro Plus and TheSky 6. What has Unk been using, then? The ancient DOS app, Skyglobe 3.6. For years and years.

Despite its age and the undeniable clunkiness of its graphics, Skyglobe was all I needed for quick looks at the sky. It was fast to load, blazingly fast, and getting the area of the sky I was interested in centered was the work of a few seconds. I’d probably be using Skyglobe still if my Windows XP laptop hadn’t gone belly up.

Even before the tragic death of my Toshiba Satellite, I’d been searching for a Skyglobe replacement. Surely there was a 21st century program that could do the job and was a little easier on the eyes. I’d heard about Stellarium, which was, from what I could tell, focused on showing a realistic sky rather than displaying hundreds of thousands of LEDA galaxies. Didn’t sound like something that could help deep sky crazy Unk with the Herschel Project, but it might be just the Skyglobe replacement I was looking for.

Like most other freeware programs, you obtain Stellarium by downloading it. A quick Google turned up the program’s attractive site. I wasn’t just impressed by the web page’s slick and professional look, but by what I read there. Stellarium is a group effort led by its original developer, French programmer Fabien Chéreau. While Stellarium hadn’t appeared on my radar until fairly recently, Fabien and company have been working on it for nearly a decade, and it has won numerous awards.

Though I didn’t contemplate using the program in the field to chase Herschel 2500 fuzzies, I was interested to know what sort of data depth we were talking about. It’s not up there with SkyTools 3, but it’s got a danged sight more stars and DSOs than Skyglobe did. It ships with 600,000 stars, and, near as I can tell (I have not run across an exact figure for DSOs), it has the entire NGC catalog.

It’s hardly a bare-bones program, either. The current version, v0.10.6.1, is fully capable of sending a computerized telescope on go-tos. It even has eyepiece field views, artificial satellites (the program will automatically fetch current orbital elements), and eclipse simulations. This was, I thought, clearly a program that could be used in the field whether I intended to or not.

Sound pretty good? Let’s go get it. Downloading the program is quick and easy, since it is “only” 43.4mb in size. Remember what we did with Cartes du Ciel? Do the same thing here. Mash “open” (“run” on some browsers) instead of “save” on the window that appears when you click on the appropriate file. Which file is appropriate? That’s easy to determine. Just choose the icon for your operating system (at the Stellarium web page’s top): Windows, Linux, or Macintosh (OS X only). You can also download a fairly complete user’s manual, and that might not be a bad idea.

The Stellarium manual goes a long way toward correcting one of the program’s few deficiencies. As with many freeware applications, the information on how to install and configure and operate the program is scattered across multiple web pages and Stellarium’s help system. The information is there, somewhere, but it’s not always clear where that somewhere is. The User Manual is a work in progress, but despite that and the awkwardness that comes from it being written by a non-native English speaker, it contains a lot of what you need to know.

Anyhoo, when you click “open,” the file will download and the Install program will automatically execute (depending on your O/S, you may have to click an “OK” to give it permission to proceed). Accept the Install program’s defaults and in no time it will finish and place an attractive Stellarium icon on your desktop.

The above is for Windows users; the procedure for installing Stellarium on Linux and Macintosh will differ slightly. It shouldn’t be a challenge, however, and I won’t presume to tell you what to do since you know far more about your operating system than your computer ignorant old Uncle does. I have not heard of any problems associated with installing the program on Linux or Apple.

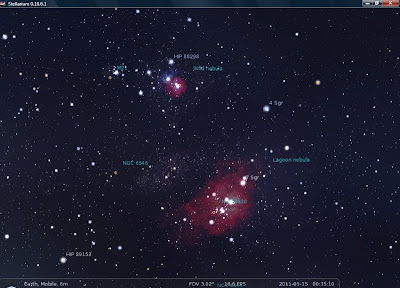

An attractive display is Stellarium’s stock in trade, so how pretty is it? I figured it would be a beaut since the website said the program is being used in honest-to-god planetariums. If its sky looks good enough to be projected on a big dome, surely it would be lovely on my 20-inch monitor. Still, I wasn’t prepared for just how good the sky display looks. When I started the program, I was gobsmacked by its beauty. It reminded me of the night I’d run Skyglobe on my new IBM PC, which was equipped with a (gasp) VGA card, for the first time and had stared in wonder at the program’s simple but beautiful depiction of the Milky Way.

The feeling was the same, but Stellarium is as far from Skyglobe as Microsoft Office is from Wordstar for CP/M. Stellarium’s sky, including sunset and sunrise and atmosphere effects, is hyper-realistic. Zooming-in on planets, the Moon, and many deep sky objects delivers photo-like images. Even the Earth is beautiful; the program ships with several lovely horizon vistas. There’s more, too: the stars twinkle, sporadic meteors flash across the heavens, and the Moon illuminates the sky appropriately. Which is all cool, but before you can do even marginally useful things with Stellarium, it’s gotta be configured. Let’s stop admiring it and start working on it.

Configuring Stellarium

So, let’s get it set up. To do that, you access the configuration menu, which is a vertical icon bar on the lower left side of your screen. “But Unk, I don’t see no icons.” That is one of the beauties of Stellarium, Skeezix. Its menus are normally hidden. To access the config menu, move your mouse pointer to the lower left of your screen, not quite the bottom, an inch or two up, and you will see an attractive and intuitive (more or less) set of icons magically appear.

First things first. As is the case with almost every other planetarium program, you need to tell Stellarium where you are latitude and longitude-wise for it to provide you with an accurate model of your sky. You do that by mashing the first icon on the config menu, which looks like a li’l compass rose.

The window that appears will give you the option of selecting your locale from a list of cities (fairly extensive), manually keying in your lat and lon, or clicking on a map. Use the last option only to set your site to general areas of the world; it is not precise enough to select an exact location. Set your position one of these three ways, and, if it’s your normal observing site, also check the box “Use as Default.”

Time settings are also a must. Close the location menu, bring the icons back, and click the one that looks like a clock face, right? Good guess, but we’ve got some nice parting gifts for you. The clock will allow you to input a particular date and time, but we are not interested in that now. Instead, click the wrench icon. While most of the left icon bar selections have to do with configuration, the one that appears when you hit the wrench is the genu-wine Configuration Menu, where you can set time parameters and a lot more.

Before we take care of time, we might as well check-out the Main tab, which will appear when you open the menu. If English is not set as “Program Language,” select it or the language of your choice. Then tick the “All Available” bubble for “Selected object information.”

Now for time set up. Click the “Navigation” tab on the Configuration Menu. If “Enable keyboard navigation” and “Enable mouse navigation” are not checked, check ‘em. Next down is the time setting, “Startup date and Time.” Tick the bubble “System date and time.”

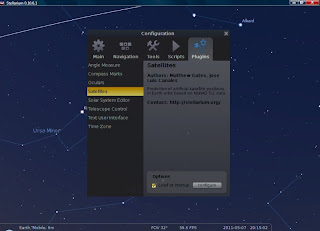

What now? You can skip the “Tools” tab. Same-same for “Scripts.” Open up the Plug-ins tab. There are various plug-ins, little helper programs, Stellarium can use. The two you’ll use most are “Ocular” and “Telescope” (the latter only if you plan to use Stellarium to send a computerized telescope on go-tos). To set ‘em up, select the plug-ins tab.

To configure eyepieces, click “Oculars” on the left and check the box at the bottom of the window “load at startup.” In order to configure the plug-in, it will have to be loaded, so close the menu, shut-down Stellarium, restart, and return to the Configuration Menu and the Plug-ins tab. The “Configure” button will now be clickable. Do so, and select the “Eyepieces” tab. Push the “Add” button, and enter the data for an eyepiece in the fields on the upper right. If you want to add another eyepiece when you are done, click the “Add” button again. You’ll need to enter telescope data as well. Select the “Telescopes” tab and key-in the particulars of your telescopes just as you did eyepieces.

If you want to control a telescope, and you are lucky enough to own one of the go-to rigs for which Stellarium has built in drivers (Meade, Celestron, SynScan, a few others), getting going is easy. Select the “Telescope Control” tab, and, just as you did with oculars, check “Load at startup,” close Stellarium, restart it, and mash the now active “configure” button.

Configuring a telescope is similar to configuring eyepieces. Click “Add” and you will be presented with a menu to fill in. At the top, ensure the bubble “Stellarium, directly through a serial port” is ticked. Below that, enter the name of the scope. That can be anything, including “Old Betsy.” Or you can just leave it as “New Telescope 1.” Don’t change the “connection delay” and tick “J2000” (normally). Scroll the scroll bar till you come to “Device Settings” and enter the computer’s serial port: “Com 1,” “Com 2,” etc. Finally, select the telescope type from the pull-down. That is it for now; everything else can be left alone. Your scope ain’t on the list? Don’t fret; Unk will show you how to use ANY telescope (just about) in a minute.

Are you interested in satellites? Artificial satellites? Stellarium can show animated “birds” crossing its screen at the proper times and places. Configuring this plug-in is easy. If “Load at startup” is not checked, check it and restart the program, yadda-yadda-yadda. When you are back at the Plug-ins tab, mash “Satellites” and “Configure.” There, all you need do is enable “Update from Internet sources” (the orbital elements, that is), “Labels” and “Orbit lines” (if you like). And that is it. The basic configuration of Stellarium is done. Well, almost. There is one more thing you might want to do…

I know you little boogers: you want MORE. “How do I add more stuff, Unk?” If you are talking DSOs, I can’t help you. Like I said back at the beginning, the program comes with what appears to be the whole NGC, and as far as I know that is all it can handle. Stars? Yes, you can add more, lots more, and it is easy to do so.

Go back to the Configuration menu if you’ve closed it and click the “Tools” tab we skipped earlier. You will see a button on the lower left that says “Get star catalog 4 of 9” (or some such). Push it to install the first of the auxiliary star files. Keep doing that until all the catalogs are downloaded. This will give you stars down to about magnitude 16, from the Hubble Guide Star Catalog I reckon, which will be plenty for most of us.

Using Stellarium Indoors

The icons are in groups, and the first three concern the constellations. The leftmost icon, little stars joined by lines, as you might have guessed allows you to turn on and off constellation stick figure lines. Ain’t it cool the way they fade in and out? The default stick figures are familiar and pretty much identical to what you see in Sky and Telescope’s monthly sky map. The next icon turns on and off constellation labels, and the one to the right of that is constellation “art,” overlaid drawings of the mythological (and other) personalities and objects the constellations represent.

Constellation art is not overly useful for most of us. It’s pretty and cool and we might look at it once in a while, but that is it. On the other hand, if you are an educator you will find your astronomy students love seeing the “real” constellations. The default in “Starlore” (selected in the vertical icon bar under Sky and Viewing Options), “Western,” is OK, but the figures look a little cartoony. Thanks to the open nature of Stellarium, that can be fixed.

Good buddy Mark Crossley has developed an incredible constellation art package for Stellarium. What he did was take all the figures from Hevelius’ classic atlas and somehow cram ‘em into Stellarium. In addition, you get to see the old dude’s antique constellation stick figures when “Hevelius” is selected in “Starlore.” How do you get it? Just go here, muchachos, and follow the instructions. Basically, all you have to do is put the downloaded folder in your Stellarium folder and select “Hevelius” in the aforementioned Starlore tab. When I turn on Hevelius, your old Unk relives the time he stared open-mouthed at the Grand Central Station ceiling to the amusement of passing New Yorkers (“Look at the hillbilly, youse guys!”)

Hokay, constellation fun over, it’s back to work. The next two icons turn on and off coordinate grids. The one on the left is equatorial; the one on the right is alt-azimuth. As with Cartes, you could have ‘em both on at the same time, but you probably wouldn’t want to (commendably, the EQ and AA grids are different colors).

The next three icons have to do with the Earth. The leftmost, “Ground,” turns the horizon landscape image on and off. You select the image in the vertical icon bar, in “Sky and Viewing Options” and “Landscape.” The program ships with a bunch and all are beautiful. The one I’ve got selected, my fave, is “Guereins,” the name of a small village near where they make Beaujolais. Do note that while you’ve got Moon, Mars, and Saturn horizons, these selections do not affect anything in the sky; just the horizon picture.

Next icon is “Cardinal Points,” which enables nice, big N,S,E,W markers on the horizon. Over from that is “Atmosphere,” which turns on and off some pretty effects, like the sky being brighter near the horizon.

The following pair of icons has to do with sky objects. “Nebulas” brings up and banishes deep sky objects (not just nebulas, clusters and galaxies, too) and their labels. Its partner, “Planetary Labels,” causes the text labels for Solar System objects (not the objects themselves) to come and go.

The next group also concerns Stellarium’s virtual sky. “Switch between Equatorial and Azimuthal Mode” can give you a view of the sky as seen by an EQ mount (with the horizon sometimes vertical). No, there ain’t much use for that that far as I can tell. Oh, be aware that while the icon for this, a little GEM mount, looks like it ort to have to do with controlling a telescope, it aint’ got nothing to do with that.

The next group also concerns Stellarium’s virtual sky. “Switch between Equatorial and Azimuthal Mode” can give you a view of the sky as seen by an EQ mount (with the horizon sometimes vertical). No, there ain’t much use for that that far as I can tell. Oh, be aware that while the icon for this, a little GEM mount, looks like it ort to have to do with controlling a telescope, it aint’ got nothing to do with that. One icon over is the much more useful “Center on Selected Object,” which does that. “Night mode” turns on a nicely done red screen display (you will likely still need a red filter over the laptop). The final icon in this group is “Full Screen Mode,” which switches between windowed and non-windowed mode. Full Screen gives the Stellarium display the most virtual real-estate, and is what the program defaults to, but I don’t use it. I like to have the Windows toolbar at my beck and call, so I run “windowed.” Please note that for this setting and a few others to “stick,” you’ll need to return to the Configuration (wrench) menu and press the “Save settings” button at the bottom.

Now we come to the plug-in buttons. To use any of these icons, you must have enabled their associated plug-ins to “Load at Startup” in the Configuration Menu. If you have, they can be very useful. One I use all the time when I am doing observing articles is “Angle Measure.” Mash this button to enable Angle Measure mode, and follow the onscreen instructions that appear. To wit: drag a line to measure the distance between two objects in the sky, left click to clear the measuring line, right click to move the endpoint, click the icon to exit. Sweet.

The next plug-in over is “Compass Marks,” which replaces the Cardinal Points with a finely ruled 0 to 360 degree “tape” along the horizon. Following that is one of the coolest features of Stellarium, Oculars.

When I heard the latest verson of the program featured eyepiece field views, my reaction was “Oh, ho-hum. Every program draws little circles on the display.” This is different and substantially cooler. Assuming you’ve set up eyepieces and telescopes in the Configuration Menu, select an object, M13, say, and click the Ocular icon. Up will come a round window centered on M13, perfectly sized for the first eyepiece and telescope on your list. Want to change eyepieces? Easy: hold the Ctrl key (“Command” for Mac) and press the left bracket (}) or right bracket ({) key. Wanna change scopes? Hold down Shift and press them bracket keys. I love it.

Nextuns are “Satellite Hints” and “Move a telescope to a given set of coordinates.” The former, despite its somewhat confusing title, turns on and off the display of satellites and their orbital paths (assuming you have, of course, set up that plug-in). “Move” allows you to go-to R.A. and declination coordinates if your telescope is set up and enabled and cabled. This can be very handy for looking at comets, and is mucho easier to do than inputting coordinates into a dadgummed telescope hand control.

With the last set of icons, we are back to program operations. The first four advance and reverse the sky’s time, stop/pause that time, and return to system time. Want to move the sky forward to “tonight”? Click the double arrow “right” button and watch the program time clock just above it. Too slow? Click it again and it will speed up. Keep clicking until the time is as moving forward as fast as you like.

Went too fast and overshot? You’re seeing the Sun flash by like it did in 1960's The Time Machine when you saw it down to the passion-pit (drive-in movie, younguns) with Ellie Mae? Reverse with the double arrow left button. When you are on the correct time, click the single right arrow to pause. To return to system time, click the icon with the big arrow pointing down and the little arrow pointing up. And that is it except for the “on/off switch,” which you’ll use to quit the program if you are running in full-screen mode.

Stellarium is great for use indoors, for quick looks at the state of the sky. But that’s just the way I use it. For many amateurs, it will be just as useful as Cartes du Ciel outside with a telescope. No, it does not have the depth of Cartes, and your old Uncle, deep sky fool that he is, simply cannot live without the countless PGC galaxies and other obscure deep sky objects that CdC offers. But you may be able to. Hell, most of the time I am able to.

Outside with Stellarium

I gave Stellarium a modest work-out on the observing field about a year ago, and you may be interested in reading about that here. But the bottom line? If you’re just interested in looking at or imaging a relatively few relatively mainstream DSOs, Stellarium is more than sufficient. The program’s “find” utility, the magnifying glass icon on the vertical toolbar, is not fancy but it usually gets ‘er done.

Wired up your Meade-o-tron go-to rig? Click on your search results or any other object, hold down the Control key and press 1 (if you have a second telescope assigned to the program, that one will be Control 2, etc.), and the scope goes there. Since the soft can use the ASCOM driver system, it is capable of connecting to just about any telescope and is as accurate as any other planetarium program, no matter how expensive, in sending a scope on go-tos.

Other than going to go-tos, how is Stellarium out in the field? One thing I thought would be a pain was all the prettiness. I’ve tried most of the photo-realistic planetariums, and, with the exception of TheSky 6, haven’t been impressed with any for use at a scope. This one is different; its display is attractive, but even with its night-vision mode on and a red filter on the screen, it is still legible.

Not that it’s all gravy. The program has two major deficiencies. First, its information on deep sky objects is extremely limited. Yeah, when you click on a DSO you get a blurb on the top left of the display. But it’s way too brief to be much use. It gives the object type, but that is limited to whether it’s a galaxy or a nebula or a cluster. No Hubble types, no Shapley - Sawyer types, certainly no Vorontsov - Velyaminov types. You also get the object’s magnitude and its position in alt-az, hour-angle, and R.A. /dec coordinates, but that is it. I frequently need more.

The second problem with Stellarium is less dire—these days, anyhow. It doesn’t print. If you want to use its charts in the field, you are going to take a computer with you. Ten years ago, that would have been a fatal flaw, but today nobody thinks twice about lugging a laptop or netbook to the dark site. I have heard someone has developed a printing plug-in for the program, but I have neither tried nor even seen it.

It’s kinda sad in a way, but when I got comfortable with Stellarium I stopped pining for my lost love, Skyglobe. It was time to move on. Stellarium is far more attractive and full-featured while retaining the elegantly simple functionality of the old program. Its performance is most assuredly second to none: click the icon and, BANG, it’s ready to go. Stellarium will not replace SkyTools 3 or even Cartes du Ciel for all tasks, but Fabien Chéreau’s chef d’oeuvre is one of those programs that define the current state of the art in astronomy software. Download it, muchachos; you will love it no matter how you choose to use it.

Next Time: Revenge of the Attack of the Go-to Wars!

Comments:

<< Home

Unk Rod, look for StarCalk http://homes.relex.ru/~zalex/main.htm

Its very fast astronomical program.

Some additional plugins http://www.heavensat.ru/ (in Russian only mode for this site)

Its very fast astronomical program.

Some additional plugins http://www.heavensat.ru/ (in Russian only mode for this site)

HI:

I had a look at this one some time back, and was somewhat impressed. Couldn't seem to get it working exactly right, though. Based on your recommendation, I will give it another try.

I had a look at this one some time back, and was somewhat impressed. Couldn't seem to get it working exactly right, though. Based on your recommendation, I will give it another try.

A printing workaround is to take a screen snap-shot. This image can be put in your favourite (er, favorite) word processor!

Hey Uncle Rod. Did you notice that there is a button under the configuration /tools menu that lets one download 7 or 8 more sets of stars?

Thanks for the link! I did not think it would work on OS-X but boy, does it ever! The idea of "elegant simplicity" kept going through my mind when I was using it.

As it's very functional and eye-candy at that I can see teachers and such warming up to this as it has the graphics to impress this computer gaming generation.

Defiantly a keeper.

Post a Comment

As it's very functional and eye-candy at that I can see teachers and such warming up to this as it has the graphics to impress this computer gaming generation.

Defiantly a keeper.

<< Home