Sunday, September 18, 2011

My Runs

When I was a young feller in high school, my days had a certain sameness to ‘em that seems comforting now: school all day, homework, supper, maybe a little observing. Repeat week after week. That was it. Comforting now, maybe, but not so much when I lived those days. BORING was more like it.

When I was a young feller in high school, my days had a certain sameness to ‘em that seems comforting now: school all day, homework, supper, maybe a little observing. Repeat week after week. That was it. Comforting now, maybe, but not so much when I lived those days. BORING was more like it. I was an exile from a high school social scene in the Swamp that, till the end of the 60s, was Leave it to Beaver with a little Hairspray and Rebel Without a Cause thrown in. I was not a sock hop/malt shop kinda guy and will admit girls tended to scare me (yes, Unk, really!). So, outside an occasional Science Club meeting and getting on the air with ham radio (yes, I truly was an uber-nerd) there wasn't much to look forward to when the school day was done. Just that same routine...bus ride home...li'l TV...homework...supper...scope (maybe).

Until I was a senior and finally got a car, the Old Man’s cast-off 1962 Ford Galaxie (natch), yeah, I had to ride the bus home except on those infrequent occasions when I could convince Mama to pick me up at school. A hot bus with a hundred other screaming baby-boomer kids. Hot and noisy and slow.

That was a problem. We got out of school at 3:00 p.m., but the lumbering bus turned what should have been a fifteen-minute journey into at least half an hour. When I was dumped off at the entrance to Canterbury Heights, I was off in a flash down the street to an empty house. Mama could have been there, since her job as librarian at Kate Shepard Elementary got her home half an hour before me, but she was almost always hauling my much cooler and more well-adjusted brother to his after-school activities. Which was fine. That meant there was absolutely nothing and nobody to stand between me and watching whatever remained of Dark Shadows...which often wasn't much after that interminable bus ride.

You may have heard of the late-sixties-early-seventies’ gothic-horror soap opera. Watch the episodes today and you’ll see flubbed lines and falling scenery, but that was completely unnoticed then. What made Dark Shadows special was a talented cast of professionals, Jonathan Frid and company, and their writers had room to stretch. The story arcs grew to incredibly convoluted and detailed proportions covering everything from “The Turn of the Screw” to The Crucible to Dracula. Mix-in memorable music by Robert Cobert, and little Rod had the perfect escape from the dreary realities of high school.

“What in Sam Hill is this about, Unk?” I'm getting to it, Skeeter, I'm gettin' to it... If you read this here blog more than occasionally, you know how I do things, how I conduct my observing runs. But what were things like in the halcyon (supposedly) days of 60s amateur astronomy? Back before there were goto SCTs and PCs on the field? When amateur astronomy was simpler? To give you the complete picture I have to tell you about afternoons at Mama and Daddy’s.

When the credits and the well-loved theme song of Dark Shadows rolled, it was time to change channels from ABC to our CBS affiliate for The Early Show. I am still amazed I found so much to watch when all we had was three channels: ABC, NBC, and CBS. No cable TV in them days, younguns. You either had a pair of rabbit ears (a small antenna that sat on top of the TV set) or an aerial on the roof. Us? We used Daddy’s 6-meter (ham radio) beam antenna for a TV antenna when he wasn’t on the air on “six.”

The Early Show had been on for years but had never been of much interest to li’l Rod till our station, WKRG, bought a package of films that was heaven: Grade "B" monster movies, Tarzan/Bomba jungle films, and assorted and usually mucho strange science fiction movies. I loved monsters for a couple of years, going through a phase where I waited for Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine with almost as much anticipation as for The Fantastic Four’s monthly comic magazine. By the time I had my Palomar Junior I had almost outgrown monsters, though, and was more interested in the outré SF I’d see some afternoons.

We ain’t talking The Day the Earth Stood Still. That hallowed film was reserved for broadcast by NBC once a year on Saturday Night at the Movies, just like The Wizard of Oz. Nor even The Blob or This Island Earth. No, what we got on The Early Show was odd films like The Monolith Monsters, Not of This Earth, and, of course, Invaders from Mars, the story of a little kid (there’s a small refractor in his room!) who discovers monsters from the angry red planet are taking over the minds (and bodies) of adults.

The Day the Earth Stood Still. That hallowed film was reserved for broadcast by NBC once a year on Saturday Night at the Movies, just like The Wizard of Oz. Nor even The Blob or This Island Earth. No, what we got on The Early Show was odd films like The Monolith Monsters, Not of This Earth, and, of course, Invaders from Mars, the story of a little kid (there’s a small refractor in his room!) who discovers monsters from the angry red planet are taking over the minds (and bodies) of adults.

I was genuinely frightened by those Invaders. In my slightly alienated, slightly oppressed state, the idea my teachers at W.P. Davidson High School—and maybe even Mama and Daddy—were ACTUALLY cruel and hideous monsters from The Great Out There sometimes didn’t seem so far-fetched.

That was a problem. We got out of school at 3:00 p.m., but the lumbering bus turned what should have been a fifteen-minute journey into at least half an hour. When I was dumped off at the entrance to Canterbury Heights, I was off in a flash down the street to an empty house. Mama could have been there, since her job as librarian at Kate Shepard Elementary got her home half an hour before me, but she was almost always hauling my much cooler and more well-adjusted brother to his after-school activities. Which was fine. That meant there was absolutely nothing and nobody to stand between me and watching whatever remained of Dark Shadows...which often wasn't much after that interminable bus ride.

You may have heard of the late-sixties-early-seventies’ gothic-horror soap opera. Watch the episodes today and you’ll see flubbed lines and falling scenery, but that was completely unnoticed then. What made Dark Shadows special was a talented cast of professionals, Jonathan Frid and company, and their writers had room to stretch. The story arcs grew to incredibly convoluted and detailed proportions covering everything from “The Turn of the Screw” to The Crucible to Dracula. Mix-in memorable music by Robert Cobert, and little Rod had the perfect escape from the dreary realities of high school.

“What in Sam Hill is this about, Unk?” I'm getting to it, Skeeter, I'm gettin' to it... If you read this here blog more than occasionally, you know how I do things, how I conduct my observing runs. But what were things like in the halcyon (supposedly) days of 60s amateur astronomy? Back before there were goto SCTs and PCs on the field? When amateur astronomy was simpler? To give you the complete picture I have to tell you about afternoons at Mama and Daddy’s.

When the credits and the well-loved theme song of Dark Shadows rolled, it was time to change channels from ABC to our CBS affiliate for The Early Show. I am still amazed I found so much to watch when all we had was three channels: ABC, NBC, and CBS. No cable TV in them days, younguns. You either had a pair of rabbit ears (a small antenna that sat on top of the TV set) or an aerial on the roof. Us? We used Daddy’s 6-meter (ham radio) beam antenna for a TV antenna when he wasn’t on the air on “six.”

The Early Show had been on for years but had never been of much interest to li’l Rod till our station, WKRG, bought a package of films that was heaven: Grade "B" monster movies, Tarzan/Bomba jungle films, and assorted and usually mucho strange science fiction movies. I loved monsters for a couple of years, going through a phase where I waited for Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine with almost as much anticipation as for The Fantastic Four’s monthly comic magazine. By the time I had my Palomar Junior I had almost outgrown monsters, though, and was more interested in the outré SF I’d see some afternoons.

We ain’t talking

The Day the Earth Stood Still. That hallowed film was reserved for broadcast by NBC once a year on Saturday Night at the Movies, just like The Wizard of Oz. Nor even The Blob or This Island Earth. No, what we got on The Early Show was odd films like The Monolith Monsters, Not of This Earth, and, of course, Invaders from Mars, the story of a little kid (there’s a small refractor in his room!) who discovers monsters from the angry red planet are taking over the minds (and bodies) of adults.

The Day the Earth Stood Still. That hallowed film was reserved for broadcast by NBC once a year on Saturday Night at the Movies, just like The Wizard of Oz. Nor even The Blob or This Island Earth. No, what we got on The Early Show was odd films like The Monolith Monsters, Not of This Earth, and, of course, Invaders from Mars, the story of a little kid (there’s a small refractor in his room!) who discovers monsters from the angry red planet are taking over the minds (and bodies) of adults. I was genuinely frightened by those Invaders. In my slightly alienated, slightly oppressed state, the idea my teachers at W.P. Davidson High School—and maybe even Mama and Daddy—were ACTUALLY cruel and hideous monsters from The Great Out There sometimes didn’t seem so far-fetched.

Whatever was on, I sat and watched till the movie ended precisely at five. Unless, as occasionally happened, some inexplicably out of place “mushy” film was on The Early Show in place of the normal fare. Why they would sometimes slip Mildred Pierce in-between Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman and Invasion U.S.A. I still do not know. The scheduled film didn’t arrive? Temporary insanity concerning what us kids wanted to watch? If the movie was punk, which would be signaled by the absence of The Early Show’s wacky host, Jungle Bob, before the film rolled, I’d move straight to my homework.

After Mama was off work, she’d sometimes run by the house and put something on the table. Or, if he wasn't working till sign-off at the TV studio, Daddy, a.k.a. “The Chief Op” or “The O.M.,” might be home and might be persuaded to heat a can of Chef Boyardee for us. Otherwise, Mama would leave something for me accompanied by heating instructions that warned in the direst terms that I MUST turn off the oven when I was done lest I burn up both the house and my silly self. If I was lucky, the instructions were uber simple and involved a fried chicken or turkey or Salisbury steak Swanson’s TV dinner.

After Mama was off work, she’d sometimes run by the house and put something on the table. Or, if he wasn't working till sign-off at the TV studio, Daddy, a.k.a. “The Chief Op” or “The O.M.,” might be home and might be persuaded to heat a can of Chef Boyardee for us. Otherwise, Mama would leave something for me accompanied by heating instructions that warned in the direst terms that I MUST turn off the oven when I was done lest I burn up both the house and my silly self. If I was lucky, the instructions were uber simple and involved a fried chicken or turkey or Salisbury steak Swanson’s TV dinner.

While the Swanson's heated (at least half an hour in those pre-microwave days), I'd attack the homework. Which I actually liked doing. It took my mind off an empty house that, if I let it, could begin to seem spooky following the afternoon fare I'd watched on the boobtube.

In winter, I’d have to hustle after supper, as it would already be on the way to good and dark. In the spring, I had a little while to linger over that fried chicken or Salisbury steak, wrap up the homework, and plan my observing run.

On weekends or in the summertime there might not be much planning at all. A few fellow proto-nerd buddies and I had got together a little club, the Backyard Astronomy Society, the legendary BAS. If we could convince the Moms involved to haul us and our small telescopes to one of the members’ backyards, we’d put our heads together about which objects to view, “Dang it, Wayne Lee! You will NEVER see the Veil Nebula; that is for professional scopes!”

On a school night or a Saturday when the gang couldn’t get together, I’d fetch my logbook (a steno pad) and my reference materials (the latest Sky and Telescope, Stars, Norton’s Star Atlas, and The New Handbook of the Heavens) and scour them for deep sky wonders of interest.

On a school night or a Saturday when the gang couldn’t get together, I’d fetch my logbook (a steno pad) and my reference materials (the latest Sky and Telescope, Stars, Norton’s Star Atlas, and The New Handbook of the Heavens) and scour them for deep sky wonders of interest.

Actually, by the time I had moved up from my 3-inch Tasco Newtonian to the Pal Junior and begun to attack the Messier list seriously, not much planning was necessary. All I had to do was check the list to see which M-objects I’d done, which needed to be done, and which were available (determined with my Edmund Star and Satellite Path Finder planisphere). Monday through Thursday, I’d be able to get in an hour of observing in the spring and maybe a couple in the winter before Mama chased me into the house.

Time to get the gear out the door. Without Mama’s hovering presence, that was easy. Not that I had a whole lot of gear to get out. I had my Edmund Scientific Palomar Junior 4.25-inch Newtonian, a TV tray on a stand that served as my observing table, a box of eyepieces including a 1-inch (25-mm) Kellner, a ½-inch Ramsden, and a lousy ¼-inch Ramsden. I also had the Barlow that came with my Pal, but I don’t remember it working very well and it usually stayed in my room.

My eyepiece case was a small aluminum war-surplus box daddy had given me. It was about 6 x 4 x 4 inches, was furnished with a shoulder strap, was painted a smart olive-drab, and was weather (dew) proof. It worked very well—I could hang it over my shoulder and have all eyepieces at my immediate beck and call. I wish I still had it.

Time to get the gear out the door. Without Mama’s hovering presence, that was easy. Not that I had a whole lot of gear to get out. I had my Edmund Scientific Palomar Junior 4.25-inch Newtonian, a TV tray on a stand that served as my observing table, a box of eyepieces including a 1-inch (25-mm) Kellner, a ½-inch Ramsden, and a lousy ¼-inch Ramsden. I also had the Barlow that came with my Pal, but I don’t remember it working very well and it usually stayed in my room.

My eyepiece case was a small aluminum war-surplus box daddy had given me. It was about 6 x 4 x 4 inches, was furnished with a shoulder strap, was painted a smart olive-drab, and was weather (dew) proof. It worked very well—I could hang it over my shoulder and have all eyepieces at my immediate beck and call. I wish I still had it.

For field reference, I’d have Sky and Telescope if I thought I’d try some Scotty objects (many of which were too hard for me). Norton’s Star Atlas was also on the table till I could grub up the coins to replace it with the much better Skalnate Pleso (the ancestor of Sky Atlas 2000).

Finally, I had my astronomer’s flashlight, an EverReady with some red cellophane left over from Valentines day over the lens, and my Messier Computer. That was what I called it, though it wasn’t really a computer; truthfully, I didn’t know what a computer was. All I knew about ELECTRONIC BRAINS came from the vague descriptions in Arthur C. Clarke novels like The City and the Stars and what I saw on Star Trek (“ERROR! ERROR!”). My gadget had information on all the Messiers, so I figgered it was like Mr. Spock’s Library Computer.

As I’ve described before, the Messier Computer was a scroll of paper, teletype paper, on which I’d written the numbers and names (if any) and constellations of all the M-objects. I also added a short description for each (“Norton’s says this is a bright globular cluster.”) and a box to check-off when I conquered the fuzzy. This scroll was wound on the rollers of a piece of war surplus electronics gear (which me and my buddies called “radio junk”) I’d got from the Old Man. It was probably a calibration reference guide for some kind of signal generator—the roll of paper I’d removed from it was utterly indecipherable. Whatever it was, the Messier computer worked a treat, and I curse the cruel fates that decreed it disappear sometime during the 70s—I suspect during one of Mama’s yearly cleaning binges while I was far away in the Air Force.

As I’ve described before, the Messier Computer was a scroll of paper, teletype paper, on which I’d written the numbers and names (if any) and constellations of all the M-objects. I also added a short description for each (“Norton’s says this is a bright globular cluster.”) and a box to check-off when I conquered the fuzzy. This scroll was wound on the rollers of a piece of war surplus electronics gear (which me and my buddies called “radio junk”) I’d got from the Old Man. It was probably a calibration reference guide for some kind of signal generator—the roll of paper I’d removed from it was utterly indecipherable. Whatever it was, the Messier computer worked a treat, and I curse the cruel fates that decreed it disappear sometime during the 70s—I suspect during one of Mama’s yearly cleaning binges while I was far away in the Air Force.

Then there was the question of where to set up. There was a tree-free spot at the base of Mama and Daddy’s yard that allowed me to explore the deep southwestern sky, but when I was home alone I found that spot was far enough from the house to be too spooky most nights. I preferred to set up on the blacktop next to the carport. I had a pretty good view of the eastern sky (over the roof of the house; it took me a while to figure out the heat radiating from it screwed up my images), and the meridian was in the clear from the north pole till just past the Celestial Equator.

I’d detach the tube, lift the big and heavy (I thought) mount, and carefully, very carefully—I was wisely wary of nicking Mama’s beloved mahogany coffee table—maneuver the Pal’s German equatorial mount out the back door. Tube on the mount again and observing table set up and populated with my accessories, I’d try to keep my mind on preparing for my run as I waited for the stars to wink on.

Letting my thoughts turn down the strange pathways engendered by The Early Show, pathways that led past UFOs, aliens, and vampires, was a recipe for an end to my observing run before it began. I was fourteen, and monsters were now supposedly a thing of the past, kid stuff from my days of reading Forrest J. Ackerman’s sacred writings and playing “Werewolf’s out tonight!” under a fat yellow Moon with the kids next door. But with the neighborhood growing dark and quiet, suddenly none of that seemed like kid stuff at all.

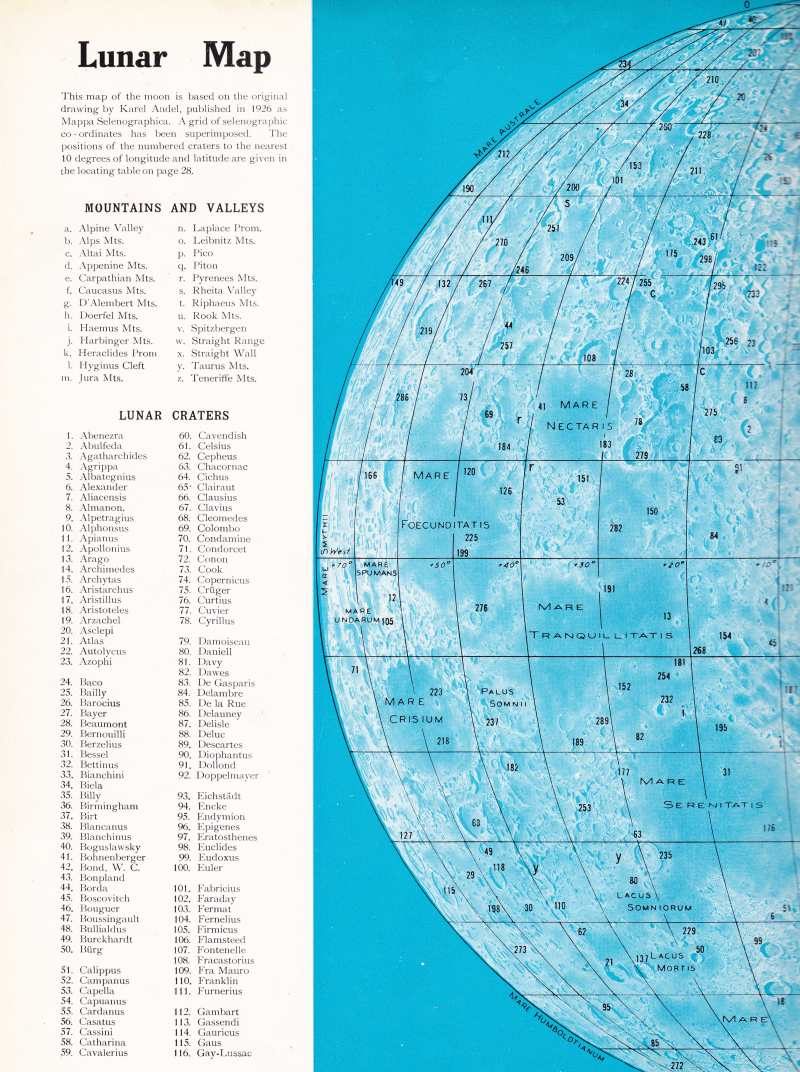

So, yeah, I tried my best to keep my mind on the sky. If I were staying close to home in the Solar System, just visiting the good old Moon, I’d review the wonderful two-page Lunar map in the old Norton’s and try to map out an evening's lunar explorations. My hero, Patrick Moore (well before he was SIR Patrick), suggested if you wanted to really learn the Moon you should sketch 100 prominent Lunar features. I kicked it up a notch, undertaking to sketch all 300 identified on the map.

Finally, I had my astronomer’s flashlight, an EverReady with some red cellophane left over from Valentines day over the lens, and my Messier Computer. That was what I called it, though it wasn’t really a computer; truthfully, I didn’t know what a computer was. All I knew about ELECTRONIC BRAINS came from the vague descriptions in Arthur C. Clarke novels like The City and the Stars and what I saw on Star Trek (“ERROR! ERROR!”). My gadget had information on all the Messiers, so I figgered it was like Mr. Spock’s Library Computer.

As I’ve described before, the Messier Computer was a scroll of paper, teletype paper, on which I’d written the numbers and names (if any) and constellations of all the M-objects. I also added a short description for each (“Norton’s says this is a bright globular cluster.”) and a box to check-off when I conquered the fuzzy. This scroll was wound on the rollers of a piece of war surplus electronics gear (which me and my buddies called “radio junk”) I’d got from the Old Man. It was probably a calibration reference guide for some kind of signal generator—the roll of paper I’d removed from it was utterly indecipherable. Whatever it was, the Messier computer worked a treat, and I curse the cruel fates that decreed it disappear sometime during the 70s—I suspect during one of Mama’s yearly cleaning binges while I was far away in the Air Force.

As I’ve described before, the Messier Computer was a scroll of paper, teletype paper, on which I’d written the numbers and names (if any) and constellations of all the M-objects. I also added a short description for each (“Norton’s says this is a bright globular cluster.”) and a box to check-off when I conquered the fuzzy. This scroll was wound on the rollers of a piece of war surplus electronics gear (which me and my buddies called “radio junk”) I’d got from the Old Man. It was probably a calibration reference guide for some kind of signal generator—the roll of paper I’d removed from it was utterly indecipherable. Whatever it was, the Messier computer worked a treat, and I curse the cruel fates that decreed it disappear sometime during the 70s—I suspect during one of Mama’s yearly cleaning binges while I was far away in the Air Force.Then there was the question of where to set up. There was a tree-free spot at the base of Mama and Daddy’s yard that allowed me to explore the deep southwestern sky, but when I was home alone I found that spot was far enough from the house to be too spooky most nights. I preferred to set up on the blacktop next to the carport. I had a pretty good view of the eastern sky (over the roof of the house; it took me a while to figure out the heat radiating from it screwed up my images), and the meridian was in the clear from the north pole till just past the Celestial Equator.

I’d detach the tube, lift the big and heavy (I thought) mount, and carefully, very carefully—I was wisely wary of nicking Mama’s beloved mahogany coffee table—maneuver the Pal’s German equatorial mount out the back door. Tube on the mount again and observing table set up and populated with my accessories, I’d try to keep my mind on preparing for my run as I waited for the stars to wink on.

Letting my thoughts turn down the strange pathways engendered by The Early Show, pathways that led past UFOs, aliens, and vampires, was a recipe for an end to my observing run before it began. I was fourteen, and monsters were now supposedly a thing of the past, kid stuff from my days of reading Forrest J. Ackerman’s sacred writings and playing “Werewolf’s out tonight!” under a fat yellow Moon with the kids next door. But with the neighborhood growing dark and quiet, suddenly none of that seemed like kid stuff at all.

So, yeah, I tried my best to keep my mind on the sky. If I were staying close to home in the Solar System, just visiting the good old Moon, I’d review the wonderful two-page Lunar map in the old Norton’s and try to map out an evening's lunar explorations. My hero, Patrick Moore (well before he was SIR Patrick), suggested if you wanted to really learn the Moon you should sketch 100 prominent Lunar features. I kicked it up a notch, undertaking to sketch all 300 identified on the map.

I’d developed an interest in drawing for its own sake a couple of years before, and somehow convinced Mama to pay for art lessons for me one summer at our little city’s art gallery in Langan Municipal Park. Mama actually assented readily, maybe because she hoped it would keep me out of the mischief she always imagined I might be getting into—if only she had realized how timid I really was. Anyhow, the lessons helped both my celestial and terrestrial drawing technique. In the process, I developed an intense crush on my instructor, a pretty young woman from our local university’s faculty. Oh, the delicious heartbreak of youth.

I’d usually (though not always) sketch what I saw of the deep sky as well. I did all my drawings, planets and DSOs, in the steno-pad that served as my log. I would later transfer some (maybe slightly wishfully enhanced) drawings into a real sketchpad. I again curse the fates that most of my early logs and sketches disappeared sometime in the 70s.

I actually didn’t make much headway with the Messier until I figured out star-hopping. Before I did, I’d try to position the scope on an object in one go after glancing briefly at its position in Norton’s. That usually meant I missed. One night, though, I had the epiphany I should be letting the stars in the area lead me where I wanted to go. M37, for example, was about half-way along and just outside a line formed by Theta Aurigae and Beta Tauri. Once I glommed onto hopping, the Messiers began to fall before me. Not that everything was easy. M37 was still tough even with careful hopping. At least I could see something when I was on the correct spot, though. It was easy to star-hop to the position of M101, but no matter how many times I did, I never saw a blessed thing.

Another obvious help that eluded me for some time was many of the Messiers would be visible even in the Pal’s humble finder scope, a puny 23mm job. Instead of setting and resetting on consarned M37’s position, a look through the finder once I was in the area might have shown this somewhat subdued cluster as a wee fuzz-spot. Strange as it sounds today, I think I had the odd idea that doing that would have been “cheating.” Go figger.

Once I was finally on the object of my desire, I'd give it a good, long look, even if I hoped to tick off a bunch of Messiers on that evening—maybe three or four. Taking my time on objects was something I had to learn, though. In the early days, I'd give a DSO maybe a minute before I was off hunting the next one. But one day it came to me that I needed to slow down and give these marvels time. I’d stare at my target for as much as half-an-hour and let my mind drift toward it, wondering which of the multitudinous stars of M37 harbored those nasty aliens from Not of This Earth. Sometimes I spooked myself so bad I was soon carrying the scope back inside fast as I could go. But it was worth it. What good was looking at the stars if you didn't do some DEEP THINKING about them?

All good observing runs come to an end. On a weeknight that end was presaged by the headlights of Mama’s car coming down the driveway. She knew to be cautious if she saw the carport light was off lest she run over her strange young son. Not much danger of that; it was hard to miss Mama’s coming and I’d have picked up my Pal and moved him to the safety of the patio at the first distant rumble of her shocking pink Oldsmobile’s Rocket 88 engine. If Daddy made it home first, I could sometimes convince him to have a look or two and thus be able to stay at the scope for a little while after Mama returned. Eventually, of course, she’d stick her head out the back door and holler, “Now Frank, you know that boy has got to get to bed!” and that would be it.

All good observing runs come to an end. On a weeknight that end was presaged by the headlights of Mama’s car coming down the driveway. She knew to be cautious if she saw the carport light was off lest she run over her strange young son. Not much danger of that; it was hard to miss Mama’s coming and I’d have picked up my Pal and moved him to the safety of the patio at the first distant rumble of her shocking pink Oldsmobile’s Rocket 88 engine. If Daddy made it home first, I could sometimes convince him to have a look or two and thus be able to stay at the scope for a little while after Mama returned. Eventually, of course, she’d stick her head out the back door and holler, “Now Frank, you know that boy has got to get to bed!” and that would be it.

Then as now, one of the best parts of the run was the aftermath. Quick bath, back in my room, snuggled down in bed beneath my Solar System and Mr. Spock posters. I’d voyage back through the wonders I’d seen that night till sleep took me. After, in my dreams, I might even roam the Moon in the shadow of razor-sharp Chesley Bonestell mountains...

Comments:

<< Home

Great blog Rod it always brings back memories of my early observing days , Edmund Sci's telescopes and eyepieces , Nortons Star Atlas, that Bonestell prints is in a frame that occupies a space over my Desk at work.

Thanks for the journey down memory lane.

Gary ( aka Satman on Cloudy Nights)

Thanks for the journey down memory lane.

Gary ( aka Satman on Cloudy Nights)

Wow, there are so many memories that we share from childhood! But for me these things are largely forgotten (until reminded by you). How on earth do you recall all this stuff in such detail? Anyhow, thanks for the great writing and reminding me of my own childhood.

I seem to remember more and more of those supposedly good old days of late...it is called GETTING OLD! LOL!

Rod,

I tought I was reading an article about me back in the late sixties and early seventies.Brings back that warm and wondrous fuzzy feeling of the "Halcyon days."

Thank you very much for the trip down memory lane.

I tought I was reading an article about me back in the late sixties and early seventies.Brings back that warm and wondrous fuzzy feeling of the "Halcyon days."

Thank you very much for the trip down memory lane.

Rod,

I tought I was reading an article about me back in the late sixties and early seventies.Brings back that warm and wondrous fuzzy feeling of the "Halcyon days."

Thank you very much for the trip down memory lane.

Post a Comment

I tought I was reading an article about me back in the late sixties and early seventies.Brings back that warm and wondrous fuzzy feeling of the "Halcyon days."

Thank you very much for the trip down memory lane.

<< Home